-

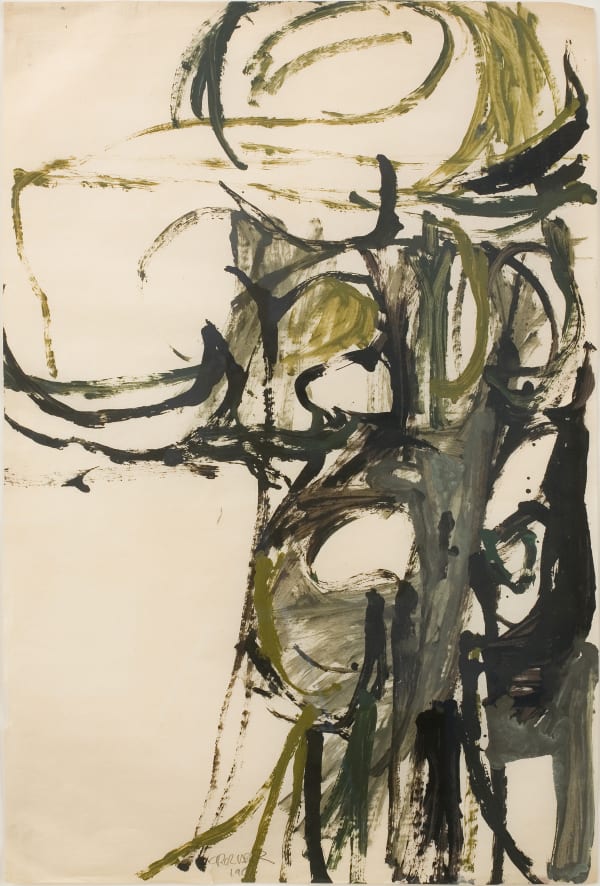

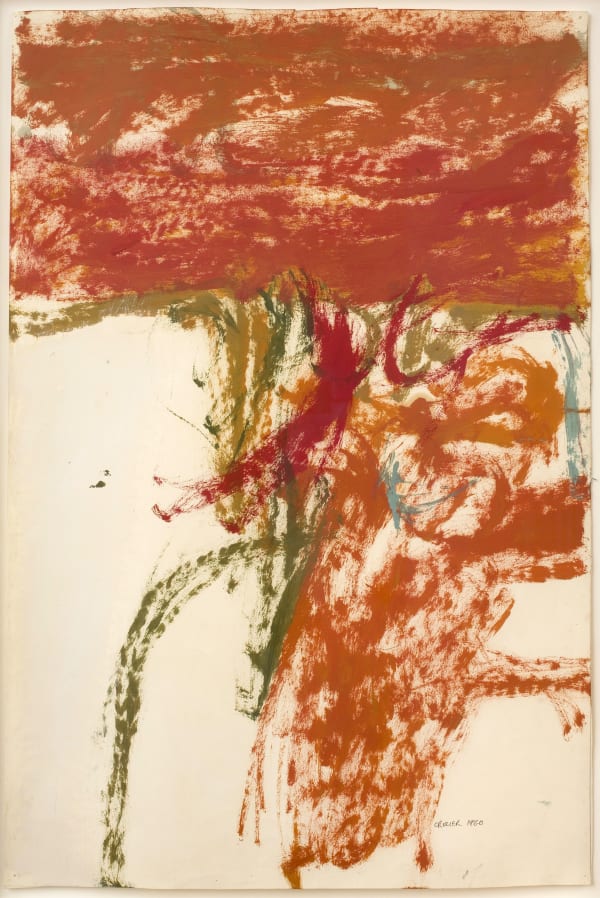

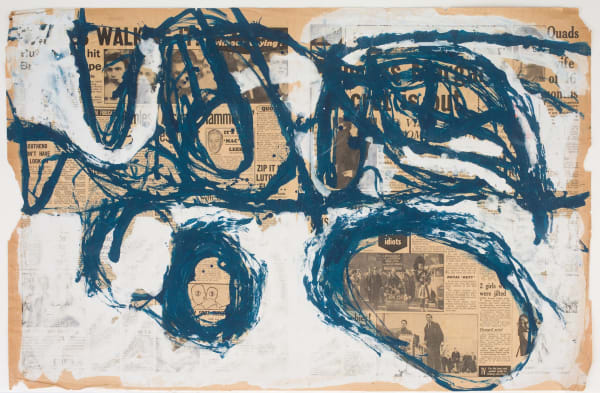

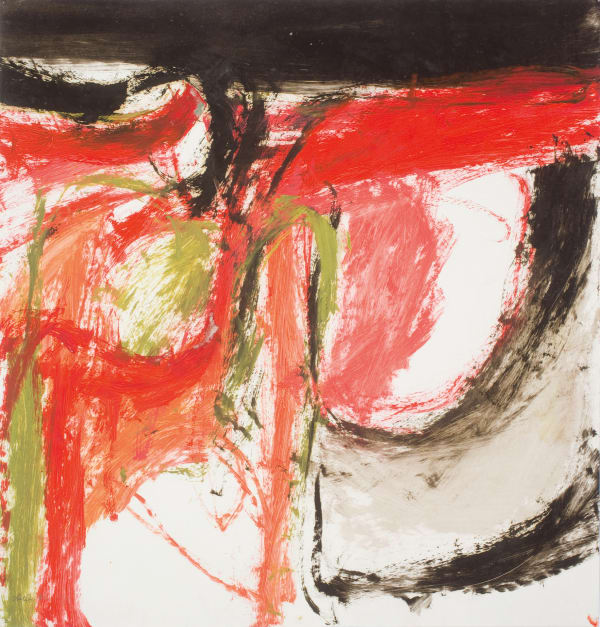

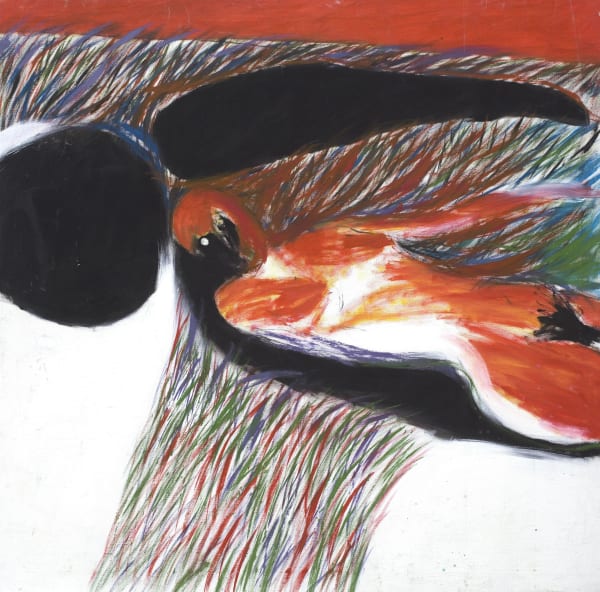

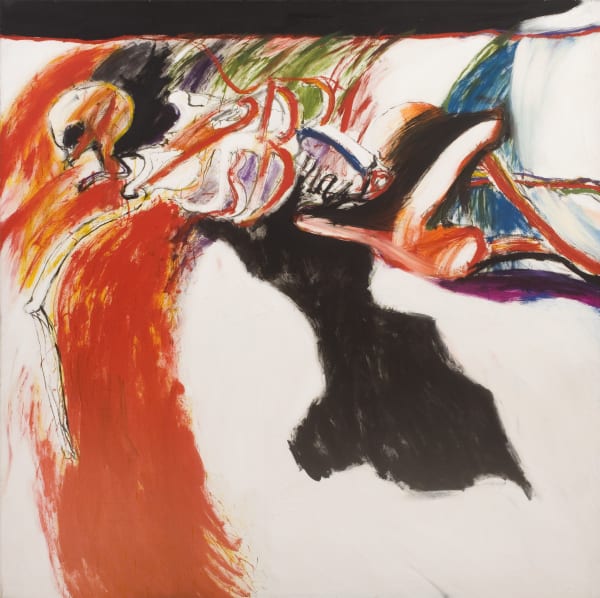

BETWEEN 1958 and 1961, William Crozier (1930—2011) was making paintings inspired by his encounters with landscape. The results were not ‘landscapes’, ‘cityscapes’ or even ‘pictures’ but freeform expressions of his subjective viewpoint. He explained in 1958: ‘[painting] is seeing with an eye preset in peculiar focus so that the painter is not seeing but re-inventing, making the apple or the landscape in the image of his own disappointment or eccentricity.’ Crozier was preoccupied by the cold war era’s insecurities, and his paintings of this period register a collective memory of Nazi extermination camps and the imminent threat of nuclear war.

Around 1960, the emergence of a skeletal figure in Crozier’s paintings reiterated his concern with mortality. It became a leitmotif of his work over the next decade. In 1958 he claimed to be uninterested by ‘the full-blown luxuriance of a grander nature’, preferring ‘the dull, repetitive life and death of nature’. Later in 1979, he described these paintings as ‘figures in a situation of stress and dilemma’. He went on, ‘it was my intention to extend the state of mind of the [skeletal] person into a depiction of the landscape.’

Despite titular references to locations in Ayrshire, Essex and London, Crozier’s abstract idiom precluded the depiction of recognisable places. The visual language of his paintings in these years—organic round-edged forms, jagged streaks, impenetrable black armatures—is an original Anglophone variety of painterly abstraction, akin to the action painting of Jackson Pollock and the tachisme of Paris-based artists such as Roger Bissière, Alfred Manessier and Henri Michaux. In these paintings Crozier conceived an art that was profound and genuine, and they reflect the intense personality of a talented young artist plotting his path through a fast changing world.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

William Crozier | Nature into Abstraction: Online Viewing Room

Past viewing_room