-

-

In 1934, Virginia Woolf described Walter Sickert as ‘probably the best painter now living in England’. Among the sources of inspiration which sustained him over a long career, none won him so much acclaim and infamy as the human face and body. After a short period as an actor, he spent his life fashioning new identities for himself and his sitters. This exhibition brings together figure paintings from across his career. Fêted for their vitality and an enduring sense of unease, many of these works were later studied and admired by post-war London painters such as Francis Bacon and Leon Kossoff.

-

1890 - 1914

In the years up to 1914, spent in Venice, Dieppe and London, Sickert’s figures and faces were by turns malevolent and nasty, sensuous and tender. Though he is best known for suggestive scenes of lust or violence, painted in Camden Town between 1906 and 1914, his depiction of men and women ranged widely. His sitters were both very old and very young, and any given individual could be recast in whatever rôle a painting required – whether victim or perpetrator, desirous or desirable. He regarded himself as a literary painter and with figures such as the haggard old woman in Mamma Mia Poverettaor the cheeky-faced girl known as ‘Chicken’, Sickert’s characters have the same vivacity as any found in the novels of Balzac or Dickens.

-

-

1914 - 1935

The year 1914 was a turning point in Sickert’s career. While he continued to depict the human face and figure, his palette grew brighter and less naturalistic, and his representation of the figure became more inventively fragmented than ever before. He was the towering artistic personality of the interwar period, with a reputation supported by paintings of unfailing originality and daring. The human figure in his late work could be any mixture of glamorous and villainous. Some of his most remarkable characterisations date from this period, including the monstrous visage of Cicely Hey – a painter friend of Sickert’s – and the dignified full-length portrait of Rear Admiral Lumsden – a tattooed naval officer he met at Brighton’s public baths.

-

-

1927 - 1942

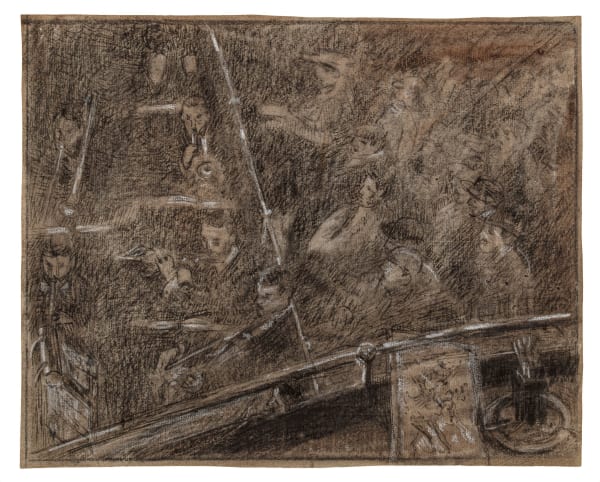

English EchoesIn 1927, Sickert began a series of work which continued until the end of his life. The starting point for each of his ‘English Echoes’ was an old black and white illustration, usually taken from Victorian weeklies like the London Journal. Though the drawing was overtly the work of an illustrator, Sickert’s dramatically scaled-up adaptations of these wood engravings was far more sophisticated than a simple copy. Gaudy colours and a cursory treatment of the paint gave these nostalgic works an ambivalent sense of modernity. The self-conscious transposition of cheap reproducible images is proof enough of Sickert’s ingenuity – a strategy which later gained widespread acceptance in the work of Andy Warhol, Richard Hamilton, Gerhard Richter and others.

-

-

Drawings and Etchings

Sickert was a compulsive and experimental draughtsman. He used thumbnail sketches to observe theatre audiences; pen and ink studies to set down a sitter; chalk and charcoal studies to evoke the light effects in an interior; and pastels to add touches of colour. His conception of drawing came not from his brief time at the Slade School of Fine Art, but from his mentor Degas: make it quick, keep it fresh, and if lucky, the artist will capture a spark of life. For Sickert, these sparks then served as the basis for his paintings and prints. He kept drawings throughout his life, occasionally making finished paintings from studies made decades earlier.

-

-

-

SICKERT: The Theatre of Life

Past viewing_room

![Walter Sickert, Collaboration [After John Gilbert], 1928-30, c.](https://artlogic-res.cloudinary.com/w_600,c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy,q_auto/artlogicstorage/pianonobile/images/view/adfee7ca9b3c101d0bd073da95e2384ej.jpg)