Henry Moore used fragmented forms to reimagine the human figure in two and three ‘piece’ sculptures. They related to a long history of antique remains in art.

InSight No. 169

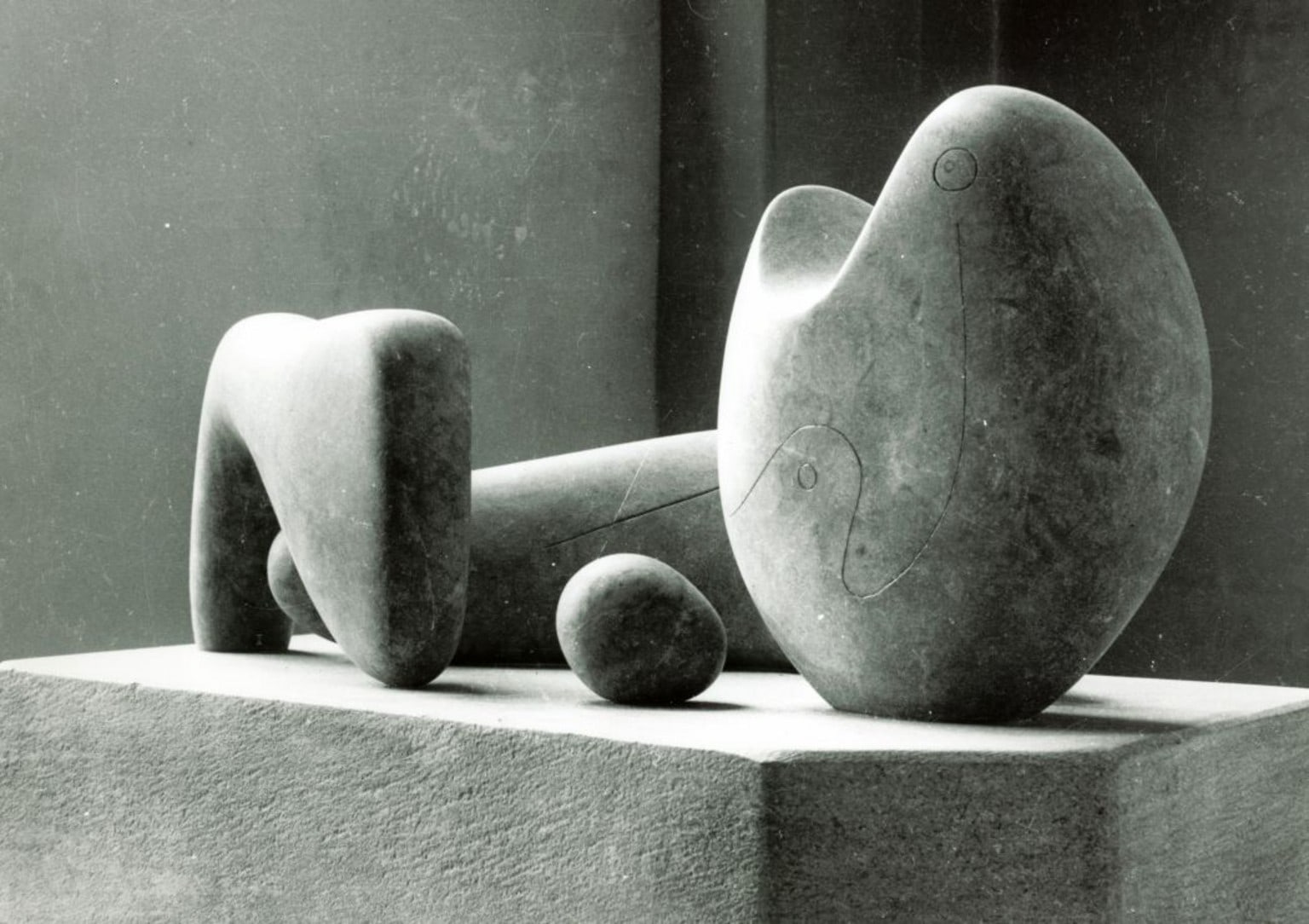

Henry Moore, Three Piece Reclining Figure Maquette No. 5, 1977

Since at least the time of J. J. Winckelmann, the fragment has been a subject of aesthetic admiration. In his history of the art of antiquity, published in 1764, Winckelmann sought to differentiate between Egyptian, Etruscan, Greek and Roman remains, and made fine distinctions about styles and periods. He asserted that one could ‘distinguish each single fragment of a statue, and say whether it is Egyptian or Grecian.’ In one instance, he recalled a sculptor who had shown him ‘the thigh, together with the knee of a kneeling figure in greenish basalt, as an Egyptian work; but I proved him, by pointing out the markings of the bones and cartilages of the knee, that it was a Greek production, in spite of the Egyptian stone.’

Whereas fragments were widely regarded as curiosities in the Middle Ages and as the remnants of great art in the Renaissance, Winckelmann’s method of stylistic analysis allowed each fragment to be parsed, understood and appreciated. In his history, he noted various modern restorations of antique fragments and criticised the inept combination of disparate fragments. In an essay describing the Belvedere torso, he wrote that a first glance revealed ‘nothing more than a misshapen stone; but if you are able to penetrate into the mysteries of art, you will behold one of its miracles’. In the eighteenth century, the classical ideal of antiquity came to encompass a cult of the fragment: around that time portions of figure sculpture came to be perceived not simply as remnants, but as artworks whose incompleteness was inseparable from their aesthetic interest. It was this cult that provided the rationale for Lord Elgin’s dislocation of the Parthenon frieze, which was removed and brought to Britain in the early nineteenth century.

Later in the nineteenth century, Auguste Rodin extended the cult of the fragment into challenging new territory with incomplete or fragmented figure sculptures. Modelling in clay allowed him to isolate, reproduce and combine different parts of a figure. His preferred terminology for such fragments, ‘abattis’, evoked a range of associations: slaughtered meat (as in giblets), body parts (as in corpses), rubble or debris (as in architectural remains), and even slashings (as in dismemberment). Bringing such irreverent connotations into the aura of the Classical ideal was a new departure in the cult of the fragment. Even as the finished artwork, cast in bronze or plaster, was redolent of antiquity, Rodin’s reimagining of the fragment established it as a vehicle for modernist formal experiments.

Just as it did for Rodin, the antique fragment had special significance for the British sculptor Henry Moore (1898–1986). It was the portal to a world of strange, sometimes contorted shapes and masses, wreathed in the gentle glow of history. Throughout his career Moore was concerned with the human figure, and his earliest work addressed a narrow range of figural types—‘head’, ‘figure’, ‘mask’, ‘mother and child’, ‘seated woman’, ‘torso’. In representations of the female figure, an erotic charge could be won by fragmenting the body and cropping the limbs to focus attention on the breasts and pudenda, thereby transforming the body into a carnal object. Moore inherited this composition from Rodin and adopted it in a torso of the mid-twenties.

Moore rapidly progressed beyond the confines of Rodinesque contractions of the human figure. In 1934, he made Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure in which four carved ‘pieces’ of Cumberland alabaster were arranged to evoke the presence of a reclined human figure. The individual stones have integrity and a richness of shape and material, even as the four stones together suggest a partial, exaggerated body. Writing in Unit 1 that year, Moore observed: ‘in sculpture the material alone forces one away from pure representation and towards abstraction.’

He was interested in organic forms and asymmetry, and in his later years he occasionally used found, unworked flint as models—either as subjects for drawing that fed his sculpture, or translated into bronze through plaster casting. Such fragments operate both within and outside the artwork, and they can at once be perceived as constituents of a complex, granular sculpture and as strangely animated detritus from external worlds (of nature, antique history, etc.). It is their amorphous quality as fragments that permits such varied associations.

Many years after his initial exploration of a ‘three-piece composition’ in 1934, Moore returned to this format with renewed interest. From 1959 until 1982, he episodically made two- and three-piece reclining figure compositions, some of which he layered with titular allusions such as ‘draped’, ‘vertebrae’ and ‘bridge prop’. A total of nine sculptures were given the title ‘Three Piece Reclining Figure’, the first of which were made in 1961–63, followed by a further group of five works in 1975–77. Some were made on a monumental scale. In these sculptures, Moore explored subtle variations in shape and the spatial interrelation of component ‘pieces’, while consistently delineating head and shoulders and often incising the head with perfunctory facial features. The reclining figure theme was among the definitive imagery of Henry Moore’s career and his multi-piece compositions were a significant development from it, at once extending the vocabulary of modernist figure sculpture and connecting with the long history of fragments.

Images:

Plaster cast of the Belvedere Torso, early nineteenth century, Royal Academy of Arts, London

Auguste Rodin, The Walking Man, 1899–1900, Harvard Art Museums, Fogg Museum

Henry Moore, Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure, 1934, Tate, photographed c. 1934–35 © The Henry Moore Foundation

Henry Moore, Three Piece Reclining Figure: Maquette No.5

Three Piece Reclining Figure: Draped (1975) on display at Yorkshire Sculpture Park in 1994

Henry Moore, Three Piece Reclining Figure: Maquette No.5