To coincide with Piano Nobile’s Viewing Room of etchings by Lucian Freud, InSight considers his friendship with ‘the great negotiator of the age’.

InSight No. 164

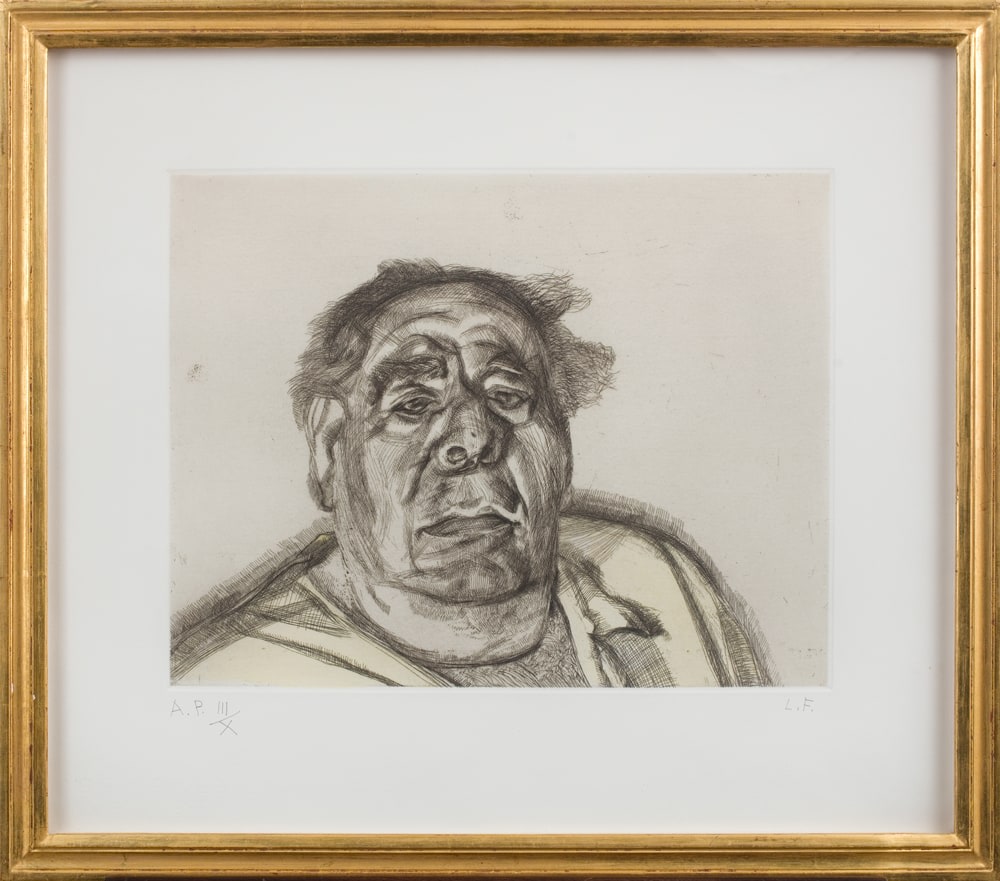

Lucian Freud, Lord Goodman in his Yellow Pyjamas, 1987

Lucian Freud (1922–2011) cultivated his relationships both carefully and impulsively. In a diary piece for the London Review of Books published in 1986, Arnold Goodman, Lord Goodman wrote that Freud had ‘in a sensationally short space of time become a very close friend’. In the compartmentalised world he created, Freud lived intensely and privately and without inhibition. The art historian Nicholas Penny has remembered Freud becoming friendly with him in 1985 after he wrote a review criticising John Pope-Hennessy’s Cellini monograph. Freud had little interest in Cellini but had an enmity for Pope-Hennessy, and he approved of Penny’s critique; this was enough to justify a lunch meeting. (Freud’s biographer William Feaver noted his ‘taste for the vendetta’, but also his appetite for friendship.) The personal connection with Penny may have smoothed the way for Freud’s bequest to the National Gallery, and the gift of Corot’s painting of an Italian woman was agreed during Penny’s tenure as director.

Arnold Goodman (1913–1995) came to be known as a deal maker. He began his career as a solicitor specialising in commercial law, but later established a hallowed, numinous position as broker, advisor, factotum. As Prime Minister, Harold Wilson benefitted from his services. In a memoir, Wilson described ‘a time in the affairs of governments when deadlock becomes total, and ordinary human agencies are impotent to deal with the situation; the superhuman is then invoked and a telephone call is put through to Lord Goodman.’ He became a public property, variously serving as chairman of the Arts Council of Great Britain and Master of University College, Oxford, among many other positions. Although Freud had met Goodman in the social orbit of their mutual friend Ann Fleming in the sixties, it was not until Freud came to appreciate his eminence—a fixer of unmatched fluency—that he invited Goodman to sit. It was Goodman who represented Freud in a dispute with the artist John Craxton about the sale of early works, of which Freud questioned the ownership and authenticity.

Between 1985 and 1987, Goodman became one of Freud’s regular morning sitters. As Goodman observed, ‘[h]e appears at the moment to have assigned me as his time-off model when he has nothing else to draw.’ Sittings took place every two or three days in the gaps between Freud’s more regular appointments. In an acknowledgement of Lord Goodman’s prestige, Freud did not study him in his studio following his usual habit but rather at Goodman’s home (an apartment in ‘a hideous nineteen-thirties block’ off Upper Regent Street, Freud recalled.)

As Goodman explained, for each of his portraits by Freud—some charcoals drawings, a pastel and an etching—he was depicted in bed:

The drawing process consisted of Lucian arriving at my home at what for me was the middle of the night, usually about 8.30 a.m. My bleary-eyed housekeeper would admit him, and the difficulties associated with bathing, shaving and dressing at that hour were summarily solved by a decision that he would draw me in bed in my pyjamas, unshaved and unbathed, before a single brush or lotion had been applied to the untouched exterior.

These arrangements considerably enhanced the interest of the resulting pictures. Illuminated by the raking light of a bedside lamp, Goodman appears desultory and dishevelled. The humanity of his gaze is amplified by the forlorn state of his creased skin and unkempt hair. Freud presumably derived some pleasure from representing an eminence grise in a state of undress. He later commented to Feaver that Goodman’s appearance reminded him of W. H. Auden’s lines, ‘Private faces in public places/ Are wiser and nicer/ Than public faces in private places.

After early experiments with etching in 1946–48, Freud returned to the medium in 1982. At first he worked on a small scale and the resulting prints resembled sketches. As his proficiency grew and after meeting the printer Marc Balakjian of Studio Prints, he started to work on a larger scale and the prints became more layered. Lord Goodman in his Yellow Pyjamas is one of the large etchings of the head and figure that Freud began to make in 1987. Freud’s etchings often developed after a painting but in this case the stimulus was provided by a pastel of Goodman wearing buttercup yellow pyjamas. The etching reorientated the pastel in a horizontal format and, uniquely amongst Freud’s etchings, retained a glow of colour; the colour of the pyjamas are indicated with a hand-applied stain of watercolour, subtly graded to harmonise with the plate tone. Lord Goodman in his Yellow Pyjamas indicates Freud’s powers of characterisation and his prowess as a technician of hatching and crosshatching. It also illustrates the unexpected friendship of two fabled men of the twentieth century.

Images:

Lucian Freud with Nicholas Penny looking at Corot’s L’Italienne, 2008, photographed by David Dawson © David Dawson

Lucian Freud, Lord Goodman in his Yellow Pyjamas (framed), 1987