In the annals of twentieth-century sculpture, the work of Lynn Chadwick stands in a line that runs from Alexander Calder to Antony Gormley.

InSight No. 161

Lynn Chadwick, Pair of Sitting Figues VIII, 1975

The principal conceit of modernist art was that it emerged spontaneously under the pressure of modernity—motor cars, air travel, computers. It had to look different from all previous art because the times were believed to be fundamentally different. Despite producing new tropes and styles, however, it had historical origins and artistic forebears. No artistic culture exists in a vacuum. In the case of Lynn Chadwick (1914–2003), the definitive reference point for his earliest work in the late forties and early fifties was Alexander Calder (1898–1976).

Calder made his first hanging mobiles in the early thirties. They upset traditional notions of sculpture in which shape, mass and volume were paramount—the mobiles were instead so weightless as to rotate along certain axes permitted by their construction, propelled by nothing but air currents. The components of this new sculptural format were branching lines of horizontal and vertical tension, which created an armature for flat, seemingly weightless planes of rounded, often colourful metal. Exploring the new sculptural decorum of levity, a quality incompatible with the classical tradition of monumental sculpture, Calder occasionally used his abstract constellations to evoke the animal kingdom: titles included ‘Elephant’ (1936), ‘Lobster Trap and Fish Tail’ (1939) and ‘Hanging Spider’ (1940).

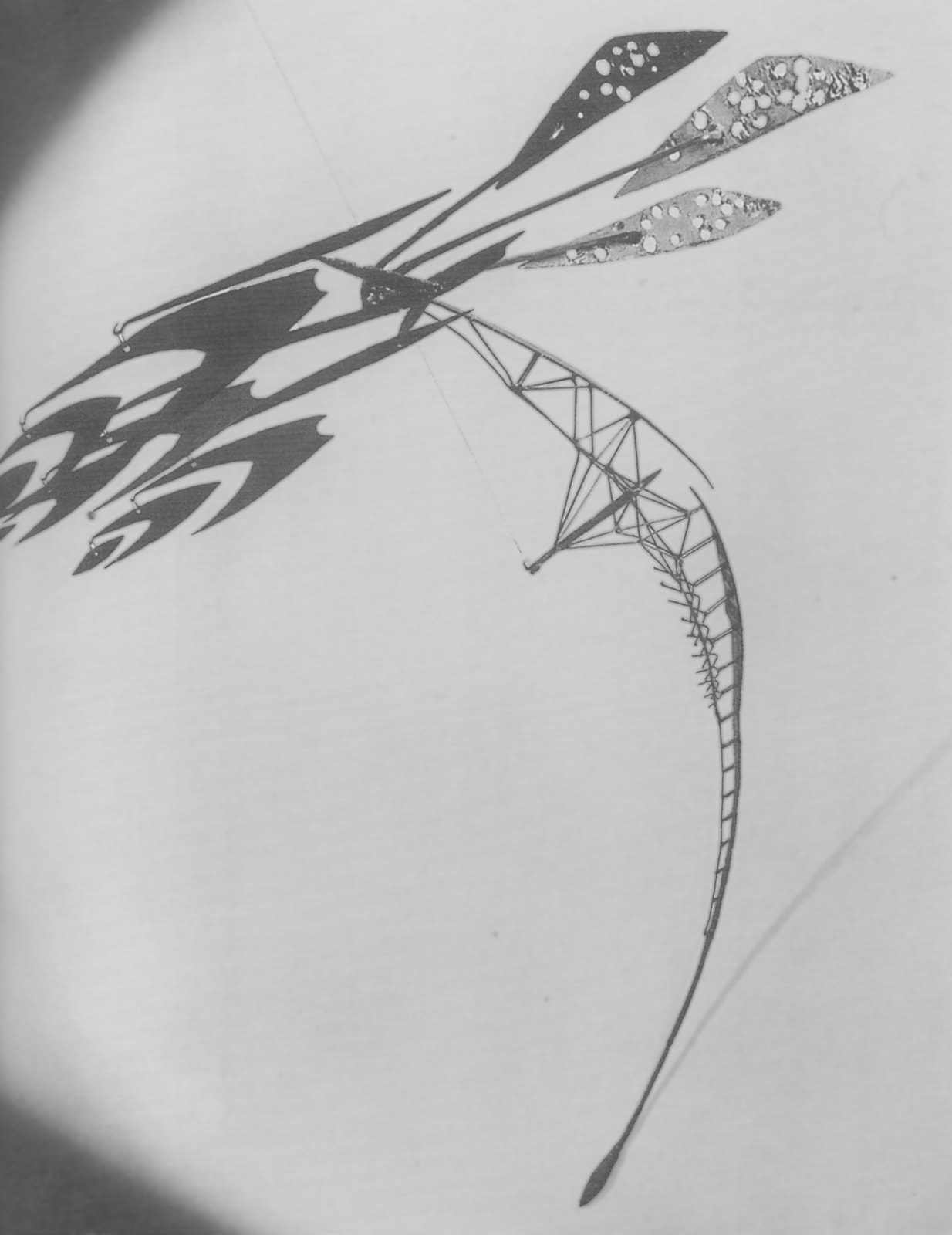

Chadwick’s interest in sculpture burgeoned after World War II whilst working as a designer of trade fair stands, in which role he collaborated with the designer Rodney Thomas. He took note of Calder’s mobiles and they were the inspiration for some of his earliest work—suspended sculptures made between 1947 and 1952, many of them simply titled ‘Mobile’. Like Calder, Chadwick also glossed the mobile format with references to animals and insects. These allusions are spelled out in the titles of ‘The Fisheater’ and ‘Dragonfly’, both made in 1951. Notwithstanding the debt to Calder, Chadwick remade the mobile format in his own personally distinctive idiom. The art critic Robert Melville appreciated this and, writing in 1957, observed that Chadwick ‘did not […] share Calder’s rather oriental vision of quietistic galaxies, and preferred to engineer jerky, unpredictable and alarming movements which give his most characteristic mobiles an air of turbulence.’

As Chadwick’s style matured, he began to fill the spindly structures of welded iron with plaster-like material called Stolit (see Insight 73). Coarse surface textures coincided with nascent allusions to the human figure. Yet his sculptural language had the quality of construction that prevented a like-for-like act of representation. His sculptures retained the facets of their composition, a series of triangles and quadrilaterals arranged to produce a satisfying sense of balance and harmony. A recurring topos in his work was the pair of figures, connected either physically or by sympathetic planes inclined to produce an interlocking unit—a format that deepened the potential for formal contrasts and patterning. Across the series Pair of Sitting Figures, for example, which included twelve pairs made between 1973 and 1975, Chadwick played with a variety of postures and shapes. He explored a wide range of subtly different reclining attitudes, leg placements and angles of intersection between the two figures. In Pair of Sitting Figures VIII, the backs produce a homogeneous, volumetric arrangement of projecting and receding surfaces. Each plane has sculptural integrity, even as it relates to the shape and mass of the individual figure and the overarching sculptural rhythm of the two-figure ensemble.

Besides the pair of figures, another long-running topos in Chadwick’s sculptural language was the winged figure. After learning a lesson in balance and movement from Calder, these works were a further development in the new sculpture of levity. Chadwick’s first winged figures were made in 1955 and he returned to this subject repeatedly until the mid-seventies. These works entered the mainstream of twentieth-century British sculpture and helped to produce the conditions under which Antony Gormley (b. 1950), an artist of the next generation, could conceive his most monumental work—The Angel of the North. Chadwick’s work forms a coherent passage in the history of twentieth-century sculpture, and its relationship to earlier and later passages reflect its continuing relevance.

Images:

Alexander Calder, Lobster Trap and Fish Tail, 1939, MoMA, New York, photographed by Soichi Sunami, 1949 © Calder Foundation, New York / Estate of Soichi Sunami

Lynn Chadwick, Dragonfly, 1951, Tate © Estate of Lynn Chadwick

Lynn Chadwick, Pair of Sitting Figures VIII

Lynn Chadwick, Winged Figure III, 1959, Nottingham City Museums & Galleries, Nottingham © Estate of Lynn Chadwick

Antony Gormley, Angel of the North, 1998, photographed by Ian Britton © Antony Gormley / Ian Britton