In the decade following World War II, Ben Nicholson forged an international reputation. His critical and commercial success was underpinned by ambitious still-life paintings.

InSight No. 160

Ben Nicholson, Nov 9-53 (walnut), 1953

In the fifties, Ben Nicholson (1894–1982) became an award-winning artist. After an extended period between 1935 and 1944 when his work was predominantly abstract and constructivist, he rediscovered a sense of joy and meaning in the composition of mugs, jugs, bottles and goblets. In a letter to his brother-in-law the architectural historian John Summerson, written in March 1944, Nicholson described his ‘first undiluted spell of ptg since war started’. ‘[N]o exagggeration [sic]to say that I’ve averaged a ptg a day for the last fortnight or so and’, he continued, ‘like a dog returning to his vomit these have been still life and fishing floats and even playing cards’. This marked the beginning of a new phase in his career, during which the table-top still life helped to win him wider international attention beyond the comparative insularity of avant-garde art circles in Britain and France.

At first, several small-scale paintings on board such as 1944 (three mugs) were intently focused on the characterful identity of individual objects and their material qualities. Other still-life paintings made between 1943 and 1949 used window-ledge compositions, entwining partially deconstructed glass and ceramic vessels with the naturalistic landscape viewed beyond. In 1945, Nicholson began to combine illusionistic arrangements of cups, plates and jugs with non-illusionistic, constructivist panels of opaque colour. It was an especially important stylistic development that significantly widened the formal capabilities of still life in his work. He exploited this device with increasing fluency through the fifties, creating an endlessly varied counterpoint between emphatically flat surface patterns and spatial effects of depth and layering.

In 1952, Nicholson won first prize in the Pittsburgh International Exhibition with his painting Dec 5—49 (poisonous yellow). This and other still-life paintings of 1949 signalled a new phase in Nicholson’s work characterised by a higher horizon line, which allowed dense arrangements of objects to fill the entire canvas, and the use of more adventurous, dissonant colour choices. Pittsburgh was the first in a succession of awards that he garnered throughout the fifties. Nov 9–53 (walnut) was one of the works included in his solo exhibition at Galerie Apollo, Brussels, in 1954, which was awarded the Belgian Critics Award. The same year he represented Britain at the Venice Biennale, alongside Lucian Freud and Francis Bacon, and received the Ulisse acquisition prize. In 1956, he won the inaugural Guggenheim International Award for his painting August 1956 (Val d’Orcia). And in 1957, he was given the International Prize for painting at the São Paulo Bienal.

Such critical endorsements contributed to burgeoning commercial success, not least in the United States. Nicholson’s first solo exhibition in the US was held at Durlacher Brothers, New York, in 1949. It included twenty-eight works completed since 1933, nearly half of which were still lifes made since 1945. From 1952, the year he received first prize in Pittsburgh, some of Nicholson’s most reliable collectors were American museums in search of his monumental, recently made still-life paintings. Between 1952 and 1957, a host of eminent art institutions acquired post-war still-life paintings including Toledo Museum of Art, Detroit Institute of Art, the Carnegie Museum of Art, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Art Institute of Chicago and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Such purchases went a long way towards canonising these works as some of the most successful in Nicholson’s long career. More recently, the prestige of this period was again demonstrated in 2016 when April 57 (Arbia 2) set the record auction price for Nicholson’s work.

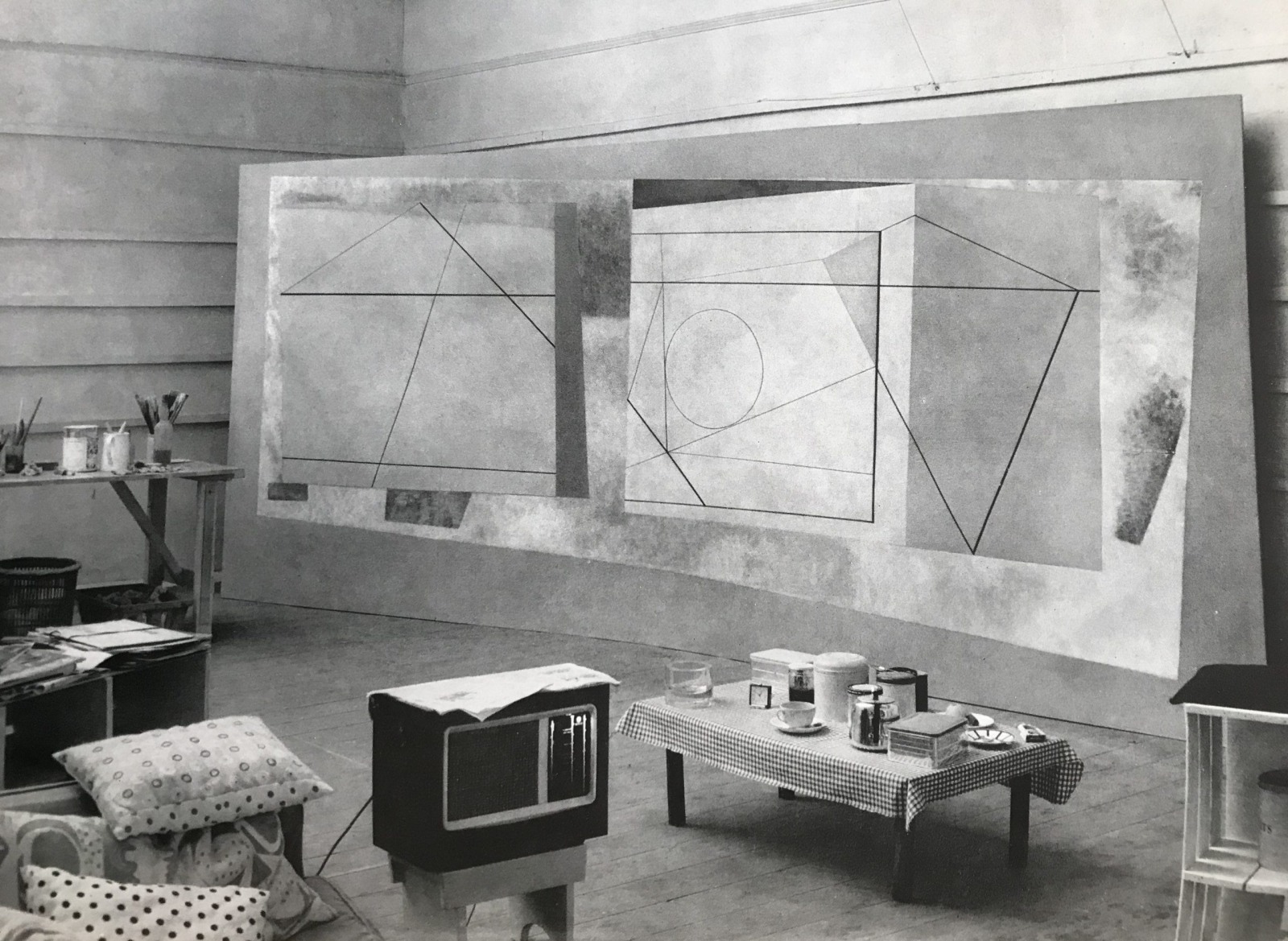

Although he appreciated his newfound recognition, Nicholson’s creative activities were motivated less by fame and prizes than the compulsive thrill of visual experiment and discovery. In 1949, he began using a studio on Porthmeor Beach in St Ives—a space illuminated by high, north-facing windows. In this enclosed atmosphere, enlivened perhaps by a blast of radio or a Jelly Roll Morton number on the gramophone, Nicholson explored new artistic territory. He seldom worked to order and never lapsed into a characteristic style.

In a painting such as Nov 9–53 (walnut), work began by rubbing thin layers of oil colour into the canvas. Then he smeared with a rag or scraped with a razor blade, blending the colours and exposing underlayers. When the ground was prepared, he made a line drawing of still-life subjects with a hard pencil—a goblet on the left, another in the middle, a third on the right with a fluted stem, others in between and behind. As the painting developed, the interlocking shapes of glass and ceramic vessels became an abstracted pattern ripe for manipulation. Areas of negative space were emphasised with shading; the overlap between certain objects was exaggerated by the application of opaque colour. The composition developed a rhythm more complex than any preparatory process would have permitted, and new dissonances and harmonies were discovered as work progressed.

Much of Nicholson’s work between 1949 and 1958 had a formal, hermetic quality. Yet a surprising range of references and associations emerged through his intuitive creative process. The gently arcing horizon line at the top of Nov 9–53 (walnut) registers at the scale of landscape. The chromatic spectrum of brown and grey evokes materials of wood and stone. The subtitle, ‘walnut’, indicates the gnarled baroque shape at the centre of the painting, nutty colours of amber and pale cream, and the substantial heft of wood harvested for furniture. But the true subject of Nicholson’s still-life paintings was necessarily elusive, as he himself argued. He was responding to the problem, as his friend John Wells expressed it, ‘how can one paint the noise of a beetle crawling across a rock?’

Images:

Nicholson’s studio at Porthmeor Beach, St Ives

Ben Nicholson, Nov 9–53 (walnut), (detail)

Ben Nicholson, Nov 9–53 (walnut), (framed)