Ben Nicholson’s relief carvings are a landmark in the history of modernist art. It was a new kind of art that married the tableau format of painting with the spatial complexity of sculpture.

InSight No. 157

Ben Nicholson, December 1933 (first completed relief), 1933

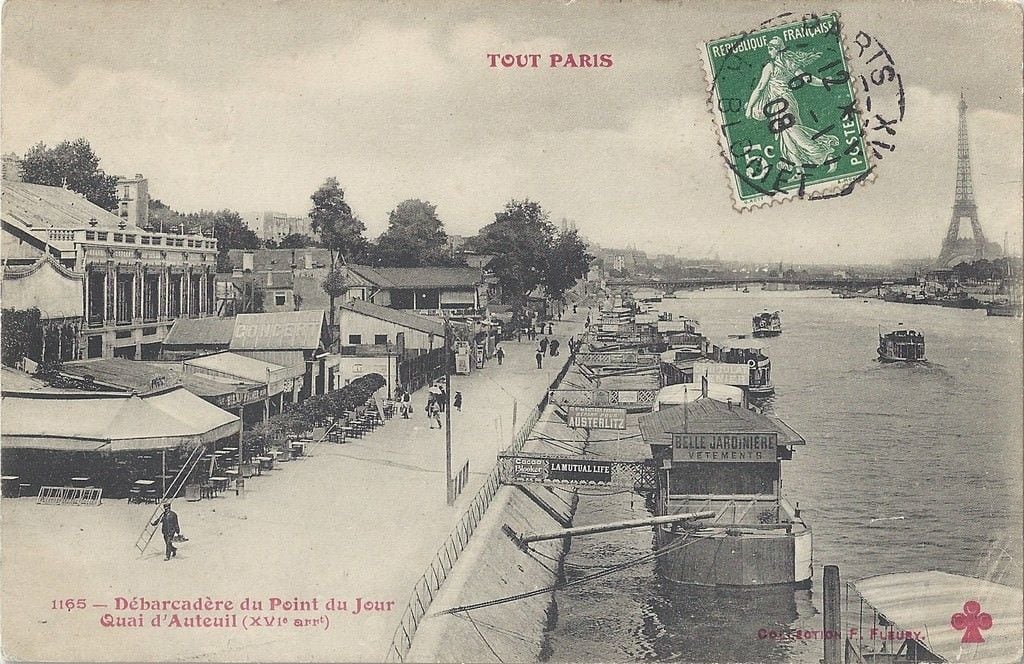

In late 1933, Ben Nicholson (1894–1982) was feeling unwell. ‘My pain is nearly gone—until it is I cannot go out in this weather’, he wrote in a letter on 12 December. He was on a visit to Paris where he stayed with Winifred Nicholson, his first wife from whom he had recently separated, and their young children Jake, Kate and Andrew. Back pain and a cold kept him inside, but he continued to work. To his new partner Barbara Hepworth, he wrote, ‘I had a very good very long working day 10 [am] to 12.30 pm.’ Such long hours of work were partly inspired by his surroundings. Facing south east, Winifred’s flat overlooked the Seine between Pont Mirabeau and Pont de Grenelle. (The address, Quai d’Auteuil, has since become Quai Louis Blériot.) From here Nicholson surveyed the river, its traffic and the changing light, and these things filled him with enthusiasm for work. One painting he made was, to him, ‘like sunlight on a clear frosty day—indeed exactly what the day is.’

Upon his arrival, he wrote: ‘This room is very like work’. Although the winter was cold, it was serene. ‘It is such lovely clear bright frosty sunny weather here—bitterly cold—the barges go by covered with frost and the men steering have braziers […] I would like to be out and skating—but working is even more exciting.’ Whilst staying with Winifred, he used a work bench of his own construction. ‘I have put the top of another table onto a small square table […] with 2 cross sections to hold it in position’. It was ‘the best work table I have had.’ It was presumably this table on which December 1933 (first completed relief) was carved and painted.

The qualities of the work emerged gradually through a process of crafting the material. The surface is multiply scored with lines and arcs that do not form coherent shapes, suggesting a speculative activity—much as the shapes in recently made paintings such as 1933 (milk and plain chocolate) seem to have emerged through improvised cycles of statement, obfuscation, scraping back and reiteration. Two incised arcs ripple outwards around the smaller circle in December 1933 (first completed relief), the fragments of unresolved circles. Colour was not applied in solid areas: some was thinned; brush texture registers at the surface in certain areas; except in the two circles, an underlayer of sandy colour is visible; the upper circle was painted in more than one hue, and local applications of pale pink create a broken outline at the edge, softening the contour. Each act of work—applications of paint, ruled pencil lines, speculative incisions in the plaster-like surface—was made to register. Unlike in the traditional practice of picture-making, where earlier stages (of drawing, squaring-up, deadcolouring, repainting) were concealed beneath a ‘finished’ surface, Nicholson did not conceive of any phase as merely preparatory: from the beginning every creative act had integrity, and it was important that the quality of each should be legible in the object.

When first exhibited at Unit 1 in 1934, this work was called ‘Two Circles’. Only later did Nicholson rename it ‘first relief’, when it was illustrated in his 1948 Lund Humphries monograph, and then more precisely as ‘first completed relief’, when it was shown in a retrospective at the Tate Gallery in 1969. That exhibition was curated by Charles Harrison, who later explained the significance of Nicholson’s breakthrough into carving in his book English Art and Modernism 1900–1939: ‘A line now became not something drawn to suggest space or outline on the surface of a picture, but the meeting of two actual planes in real space.’

Although Nicholson had made playful experiments in abstract painting as early as 1924, only in December 1933 did he begin to make non-representational work a sustained aspect of his artistic activity. Over the next three months, he made several more painted relief carvings, each of which used a narrow range of delicate natural colours—‘sandy’, ‘very pale grey’, ‘white’, ‘dark brown’, ‘yellow brown’, in his own description of 1933 (six circles). In February 1934, a further significant development was made when Nicholson dispensed with contrasts of tone and colour, and made a relief that was pure white. The change coincided with the use of ruler-drawn lines and compass-drawn circles. The signs of handicraft became less overt, even as many of the white reliefs continued to use subtly contrasting textures and irregular geometry that reflected Nicholson’s craftsman-like techniques.

Nicholson believed in echelons of truth and reality that lay beyond the visible, and his reliefs formed a physical activity of burrowing towards an idea—something ‘that our spirits alone can understand’, as Barbara Hepworth wrote in 1933—concealed within the materials of his art. Along with Hepworth and Winifred Nicholson, he was a practitioner of Christian Science in the period when December 1933 (first completed relief) was made. Asserting a form of philosophical idealism, Christian Science holds that Mind is the only genuine form of reality and that matter is merely an illusion. Nicholson’s desire to excavate his paintings and reliefs, scraping into them and using contrasting colours to evoke successive parallel planes receding beneath the surface, indirectly reflected the belief system to which he adhered. These ideas, along with the burgeoning of modernist art in Paris, to which Nicholson contributed, and the example of Hepworth’s practice in sculpture, formed an important context for the advent of relief carving in Nicholson’s work.

Images:

A postcard of Quai d'Auteuil, Paris, c. 1900

December 1933 (first completed relief) (framed)