As Piano Nobile prepares to open an autumn display of abstract painting made in sixties Britain, InSight considers the cultivated eccentricities of Alan Davie and the symbolism of his work.

InSight No. 156

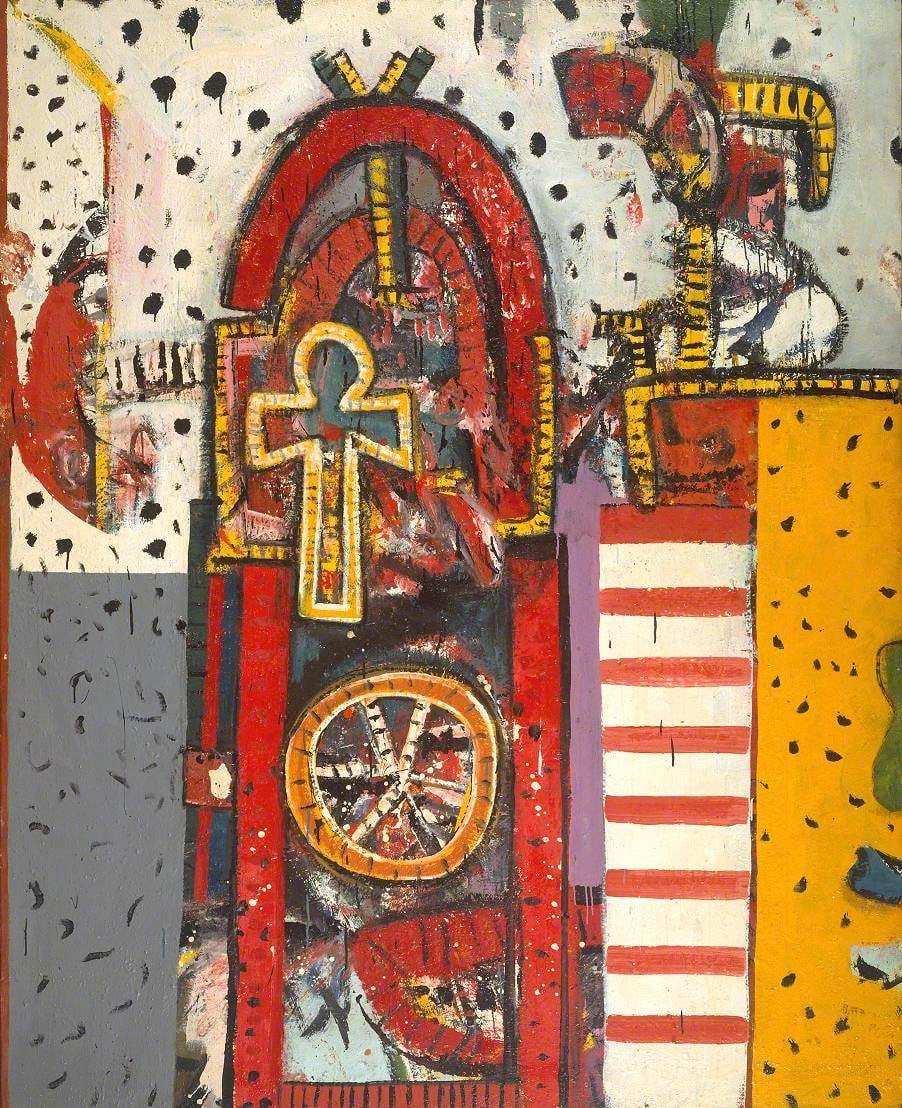

Alan Davie, Dragon's Eggs Assorted, 1962

‘Art just happens, like falling in love.’ In the unorthodox estimation of Alan Davie (1920–2014), who made this statement in 1958, nothing was more natural than making a painting. It was an extension of living and just as hard to define as life itself. ‘Art is the evocation of the inexpressible.’ He rejected art as self-expression—which he regarded as a reduction—and rather thought of it as a path to understanding better the elementary fact of existence: ‘I do not practise painting as an Art; and the Zen Buddhist likewise does not practise Archery as an exercise of skill but as a means to enlightenment.’

Davie began to make paintings in a mature idiom in the mid-fifties, by which time he had already worked as a poet, a jazz musician and a jewellery maker. These activities equipped him for painting as no other artist of his generation was equipped. In his work, the rhythm of both forms and their realisation in swift, reiterative motions of the brush suggest a peculiar jazz-inflected musicality. The imaginative titles of his paintings, always addended once finished and never descriptive or explanatory, often have the same gnomic vitality as his poems. Shorn of punctuation, loaded with mixed similes and metaphors, and usually stacked up in a column of short lines, poems like Twilight(1942) are playful and cacophonous:

A green bird swims above me

Its mate following close

The dove purrs

Like the contented cat

Then croaking

Like the invisible frog

Blackbirds squeak and cluck

Like the farmyard hen

Davie used symbols in his paintings. Circles, lozenges, ladders, stripes and spots have a portentous quality, communicating or referring to things that can never be articulated. He sometimes gave these elementary shapes allusive titular labels, such as the round and ovular forms in Dragons’ Eggs Assorted. Other associations that Davie accrued to these and similar shapes include a wheel, a target, an egg, a ball, the moon, an eye (Elephant’s Eyeful, for example). Painted with increasing clarity and definite outlines from 1960 onwards, these symbols at times evoked shamanic settings in which the architecture of colour and mark-making were at once the temple itself and the magic performed there. It was a period of growing critical recognition for Davie and the British Council selected him, along with Eduardo Paolozzi and Keith Vaughan, to be exhibited at the São Paulo Bienal in 1963, where he was awarded the painting prize. Dragons’ Eggs Assorted, painted the previous August, was one of seventeen works by Davie in the exhibition.

Unlike the Situation Group, Gillian Ayres, Bernard Cohen and Robyn Denny amongst its members, the first exhibition of which was held in 1960, Davie resisted the surging hegemony of contemporary New York painting and challenged the narrative that took non-representational painting for an American phenomenon. In his statement of 1958, written for a solo exhibition at Whitechapel Art Gallery, he rejected the categorisation of his work as ‘Action Painting’. His outlook was rather rooted in a sense of his ‘Celtic heritage’ and a critical attitude towards ‘the modern age’. To him, the machine was merely ‘an attempt by modern man to find a most elaborate symbolism.’ In his paintings, he reached for a symbolism that was contrastingly organic, singular, knotted instead of geared.

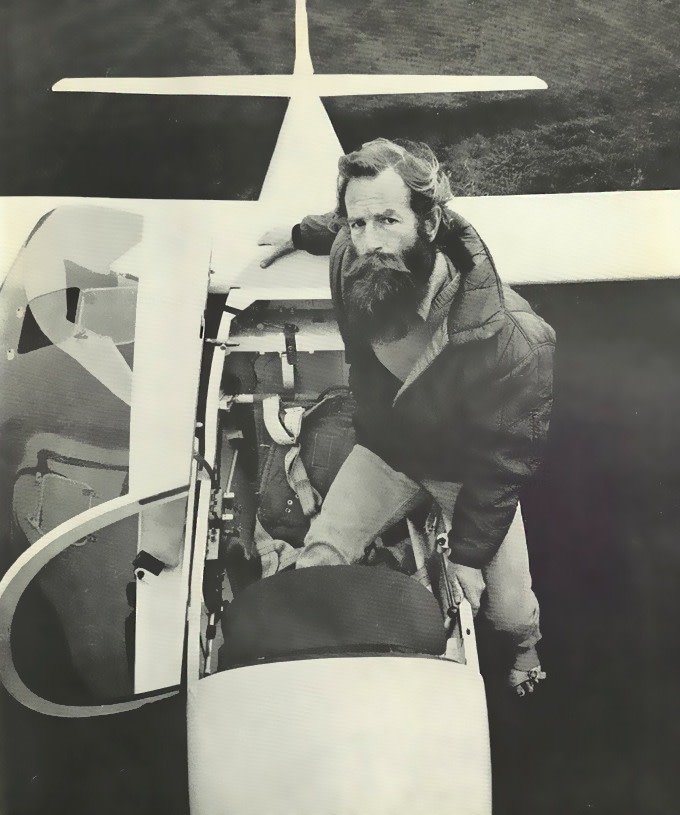

Like his contemporary Peter Lanyon, Alan Davie went gliding and relished the sensation of flight:

I am vertical

STICK RIGHT BACK KEEP WINGS LEVEL

I am supposed to be upside down 40 knots

but this is just an illusion they are watching from the ground

the ground the ground is rushing up to me again 70 knots

BLOODY MARVELLOUS

His excitement registers clearly in this extract from a statement of 1963. Without imposing a narrow interpretation on any given work, Davie’s paintings sometimes imply an aerial perspective as if picturing a landscape viewed from immediately above. The immanence of an image may have arisen from the exhilaration of remembering ‘the ground […] rushing up’. As he wrote, ‘What a curious thing to be standing on the rudderpedals looking vertically downward. I could see little patches of small round trees in perfect rectangular fields, all a kind of yellowish green, coming up at me.’ Such a description might be approximated to a painting such as Dragons’ Eggs Assorted. But it was never Davie’s intention to be descriptive. Each painting rather insists, as he wrote in 1963: ‘THIS IS IT’.

Images:

Alan Davie climbing into his sailplane at Cambridge Gliding Club, c. 1967, photographed by David Ware

Alan Davie, Elephant’s Eyeful, 1960, The Whitworth, University of Manchester © The Artist’s Estate

Alan Davie, Entrance for a Red Temple No. 1, 1960, Tate © The Estate of Alan Davie

Peter Lanyon, Dry Wind, 1958, Private Collection © The Estate of Peter Lanyon