Emerging shortly after Eric Gill and Jacob Epstein and half a generation before Barbara Hepworth and Henry Moore, Frank Dobson was hailed as the pre-eminent British sculptor of his day.

InSight No. 155

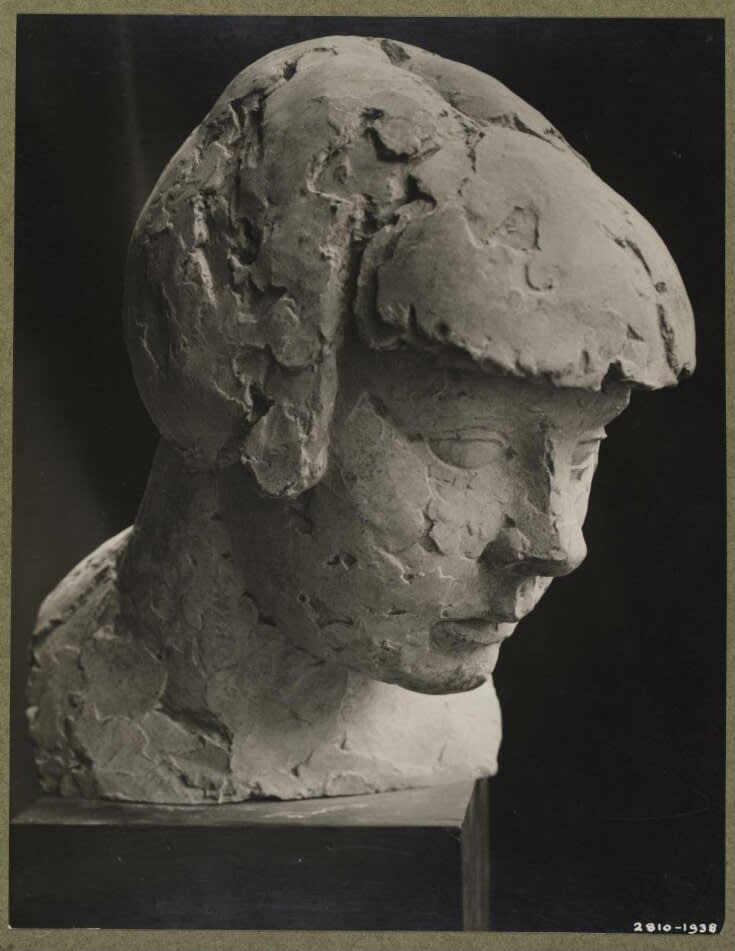

Frank Dobson, Head of a Girl (Study for Cornucopia), 1925

‘Can there be a high degree of veritable glyptic quality in work produced by hands which are habituated to the plastic method?’ Writing in The Art of Carved Sculpture in 1931, Kineton Parkes posed this question about contemporary sculptors’ dilemma between carving or modelling in clay. He was writing specifically about Frank Dobson (1886–1963), who saw no contradiction in pursuing both practices concurrently. He modelled Head of a Girl (also known as Study for Cornucopia) using plaster, while the presentation work to which it relates, Cornucopia, was carved from Ham Hill stone. He later had three uneditioned bronze casts made from the plaster study, one of which was donated to the Tate collection by the Contemporary Art Society in 1929. Another is illustrated above.

Dobson’s early carvings in wood and stone show his appetite for recent modernist developments in sculpture. A work in stone such as Two Heads, carved in 1921, glosses ‘primitive’ culture—imagined from a soup of ‘Negro sculpture, Peruvian art, Egyptian, Assyrian, Polynesian, and […] archaic Greek sculpture’, which Dobson wrote of discovering in the British Museum—and muscular exaggerations of the kind practised by Dobson’s slightly older contemporary Jacob Epstein. The long fingers of the hands encase the faces, framing them and hinting at the block-like volume of the stone from which they were cut. In 1920, Dobson participated in the Group X exhibition, staged at the Mansard Gallery in Heal’s on Tottenham Court Road, which included many Vorticist artists still orbiting Wyndham Lewis at that time. Some work by Modigliani had been shown the previous autumn at the Mansard Gallery, and these circumstances well represent the pressures under which Dobson’s early work was formed.

By the mid-twenties, however, primitivist mannerisms were a less important feature of his work. The control and expressive projection of volumes became central to his practice, and the nude female figure was the definitive subject of his mature work. Sculpture was overwhelmingly the preserve of male artists at the time, and the eroticism of swelling breasts, buttocks and hips was blandly accepted as an agreeable manifestation of ‘pure form’. In 1925, describing a full-figure study for Cornucopia in an article about Dobson published by The Burlington Magazine, Roger Fry wrote of how ‘the comparative simplicity of the plastic scheme has allowed the artist scope for a freer and easier handling and more play to his sensibility.’ Whereas the philosopher T.E. Hulme once branded Fry ‘a mere verbose sentimentalist’, this comment rather suggests Fry’s error was to devalue subject-matter and treat it reductively as a ‘plastic scheme’.

In a period photograph of the original plaster for Head of a Girl, the work is dramatically illuminated from above and set against a black background. A copy of this photograph was owned by Kineton Parkes, who bequeathed it to the Victoria & Albert Museum as part of his photographic collection in 1938, and it was also reproduced in Fry’s Burlington article. Describing Head of a Girl as a ‘charming bronze’ (ignoring the plate, which showed the plaster model), Fry suggested that ‘a very living and rather unexpected movement has been most ingeniously and subtly compressed within the narrow and exacting limits of the bust form.’ The surfaces of skin and hair have a uniform texture produced by broad, smooth scrapes of the plaster. The girl’s attitude—the head downcast and turned to the left—and her sombre gaze are delicately characterful, while her rounded facial features and coiffeur—a short bob and fringe—suggest her youth. Notwithstanding the sensitivity of this characterisation, Dobson handled his material in shapely units with crisp outlines and crests, especially evident in the protruding, undercut wave of her short fringe. The haircut is à la mode, vaguely suggestive of Bright Young Things, and contributes significantly to the period flavour of Dobson’s Cornucopia and this related study.

In his article about Dobson, Fry meditated on what defines sculpture as an artistic pursuit. ‘The sculptor interprets the solid forms of nature in solid forms.’ He characterised sculpture as ‘par excellence the art of primitive peoples and of early civilisations’, because ‘for the sensibility and mentality of these stages of civilisation sculpture was the simplest and most attainable expression for the sense of visual form.’ To Fry, it was the ‘purely sculptural plasticity’ of Dobson’s work that distinguished it from that of all his peers: ‘For whether we like his work or not, we must admit that it is true sculpture and pure sculpture, and that this is almost the first time that such a thing has been even attempted in England.’ Such recognition from the eminent British critic of the period was a high point in the critical reception of Dobson’s work—just a few years later, in 1931, Jacob Epstein was declaring Henry Moore as ‘the one important figure in contemporary English sculpture.’

IMAGES

Photograph of Head of a Girl by Frank Dobson, c. 1925, Victoria & Albert Museum, London

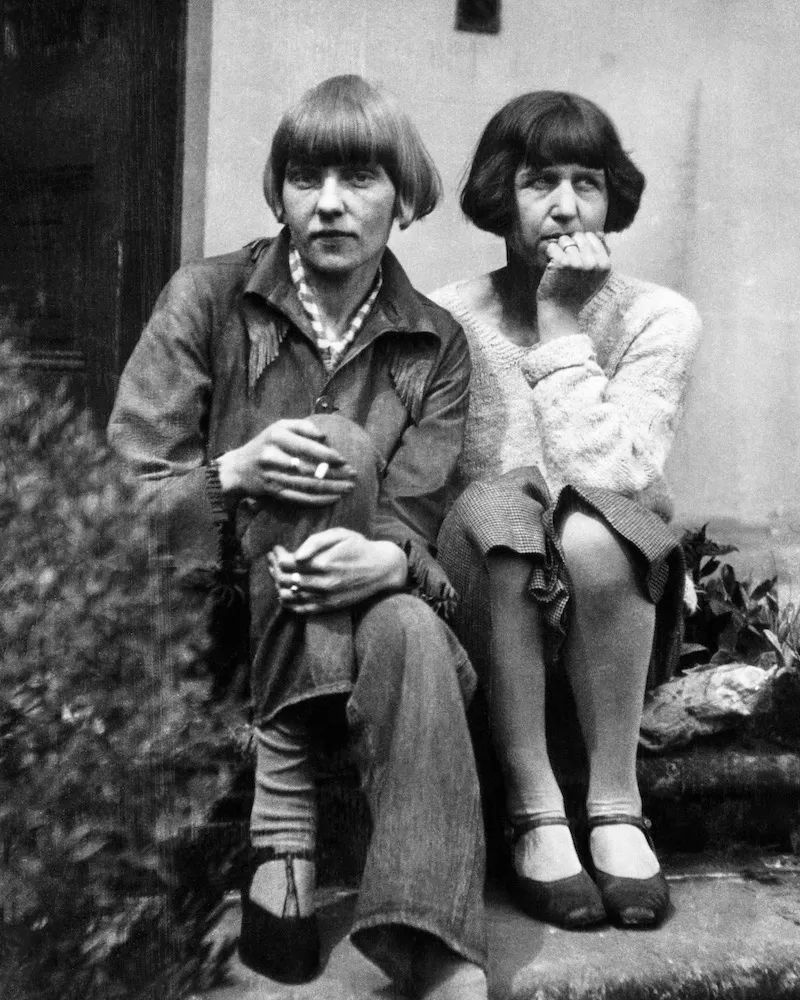

Dora Carrington and Iris Tree at Ham Spray, Wiltshire, 1929, photographed by Lytton Strachey

Head of a Girl (Study for Cornucopia) (detail)