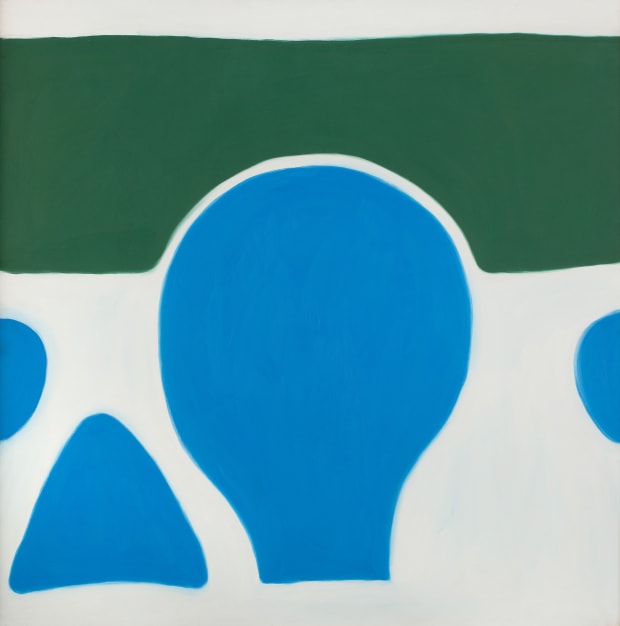

In abstract paintings made in the late fifties and sixties, William Scott proved himself an inventive maker of hieroglyphs.

InSight No. 154

William Scott, Expanded, 1965

For many representational painters living through the advent, rise and hegemony of Abstract Expressionism in the years after the Second World War, scale and proportion were sources of acute difficulty. Where scale is the literal size of a canvas, proportion is the ratio between constituent components of a picture: paintings made on large and small canvases might have either grand or modest proportions, but certain representational subjects will seem out of proportion if magnified to a large scale. For a painter such as William Scott (1913–1989), renowned for depicting tableware vessels, especially spindly-handled frying pans, his established range of subjects was incompatible with the kind of ambitious, large-scale, grandly proportioned painting he latterly aspired to make. To paint a frying pan or a bowl many times its size in real life was to risk the absurd. Another way had to be found.

This challenge was crystallised for Scott by a commission to paint a vast mural filling the entrance hall of Altnagelvin Hospital in Londonderry. The completed task, consisting of fifteen panels and measuring over thirteen metres in width, was delivered after more than two years of work. In that time Scott developed a class of abstract, symbol-like shapes and formal units, executed in a painterly style that seemed to allow the possibility for each shape and unit to self-generate, emerge, reshape themselves, wriggle even. In one panel, a sequence of three rounded units, arranged in a column, flex their edges without symmetry. Another unit is flattened along its left-hand side. Others have a blob-like quality, being more square or ovular, and some are cropped by the edges of the panel. Most important was the elastic sense of scale possessed by these shapes and units: whether large or small, they retained a convincing sense of proportion.

The invention of these symbol-like units was based on an elementary formal development of Scott’s earlier bowl motif. This motif, illustrated with singular clarity in Bowl (White on Grey), was little more than a silhouette with straight horizontal top and rounded bottom. Scott subsequently manipulated this silhouette, rotating the shape and sharpening or softening its contours. The resulting motifs were ambiguous, some of them delta-like, redolent of arrowheads or beads or other archaeological fragments, and the abrupt severing of shapes at the edge of the canvas spoke further to their quality as fragments. Ancient Celtic art was one reference point for constructing these sign-like motifs, and Róisín Kennedy has suggested that the Altnagelvin mural derived one of its devices from an ancient spiral form called the triskelion.

This slippage from the literal object—a bowl—to an allusive symbol—freed from material constraints by its sign-like quality—was only possible once Scott found a way to suppress the pictorial aspect of still life. In the late fifties, he began to treat a table top populated by vessels as a manifestly physical entity fit to be recreated in paint, rather than a landscape to be illustrated. Only by thinking in this way could he plausibly title one still-life painting as Blue Abstract (c. 1959, Walker Art Gallery).

In 1963–64, living in West Berlin on a fellowship from the DAAD (German Academic Exchange Service), Scott discovered a certain hue of cobalt blue. This was the fillip for a series of large-format canvases known as the Berlin Blues paintings. Closing down possible references to music or mood, Scott said the title was merely literal. Charged with the artist’s deepened understanding of symbols and his new freedom to work on a large scale, paintings such as Expanded are abstract whilst creating monumental signs, non-lingual and indecipherable. Shedding ‘the ties of easel painting’, as he put it, Scott produced non-representational canvases between 1964 and 1969 that suppress painterly quality in favour of deliberately clear shapes with a runic charge. As hieroglyphs, Expanded and the other Berlin Blues paintings are invested with some special but opaque meaning, whereby shape and colour come to assume even greater importance.

IMAGES

William Scott, Expanded, 1965, oil on canvas, 48 x 48 in

Neolithic flint arrowhead, 3000–2500 BC, Amgueddfa Cymru – Museum Wales

A triskelion, c. 3200 B.C., Newgrange, County Meath

Expanded (detail)