The eclectic interests of R.B. Kitaj—boxing, painting, writing, role-play—are bundled together in a history painting that depicts multiple subjects at once.

InSight No. 152

R.B. Kitaj, Whistler vs. Ruskin (Novella in Terre Verte, Yellow and Red), 1992

R.B. Kitaj (1932–2007) revelled in early twentieth-century American pictorial art made before the onslaught of abstraction. He described it as ‘American Romantic art, swerving from downright realism to surrealism and symbolism: Blakelock, Harnett, and the magnificent Albert Ryder; Eilshemius and Joseph Stella and Hartley and Sheeler; Eakins and Homer, (best of breed); the Ashcan School and Greenwich Village art; Hopper, Marsh, Soyer, Bishop’—and so on. The work of these artists was ‘printed inside me’, Kitaj wrote.

In his large-scale history painting Whistler vs. Ruskin (Novella in Terre Verte, Yellow and Red), Kitaj adapted the composition from a picture by one of these ‘Romantic’ artists: Dempsey and Firpo by George Bellows. Both are ambitious, large-scale paintings of the human figure. A potent left hook has knocked the other man over the ropes and he falls backwards, Icarus-like, out of the ring, clattering towards the spectators below. A sense of imbalance in Kitaj’s painting, a consequence of wildly exaggerated Cézannesque bodies, is corrected by quivering horizontal lines—the ropes—that span the full width of the tableau. The viewer of the painting is implicated as the dumbstruck body falls outwards towards them.

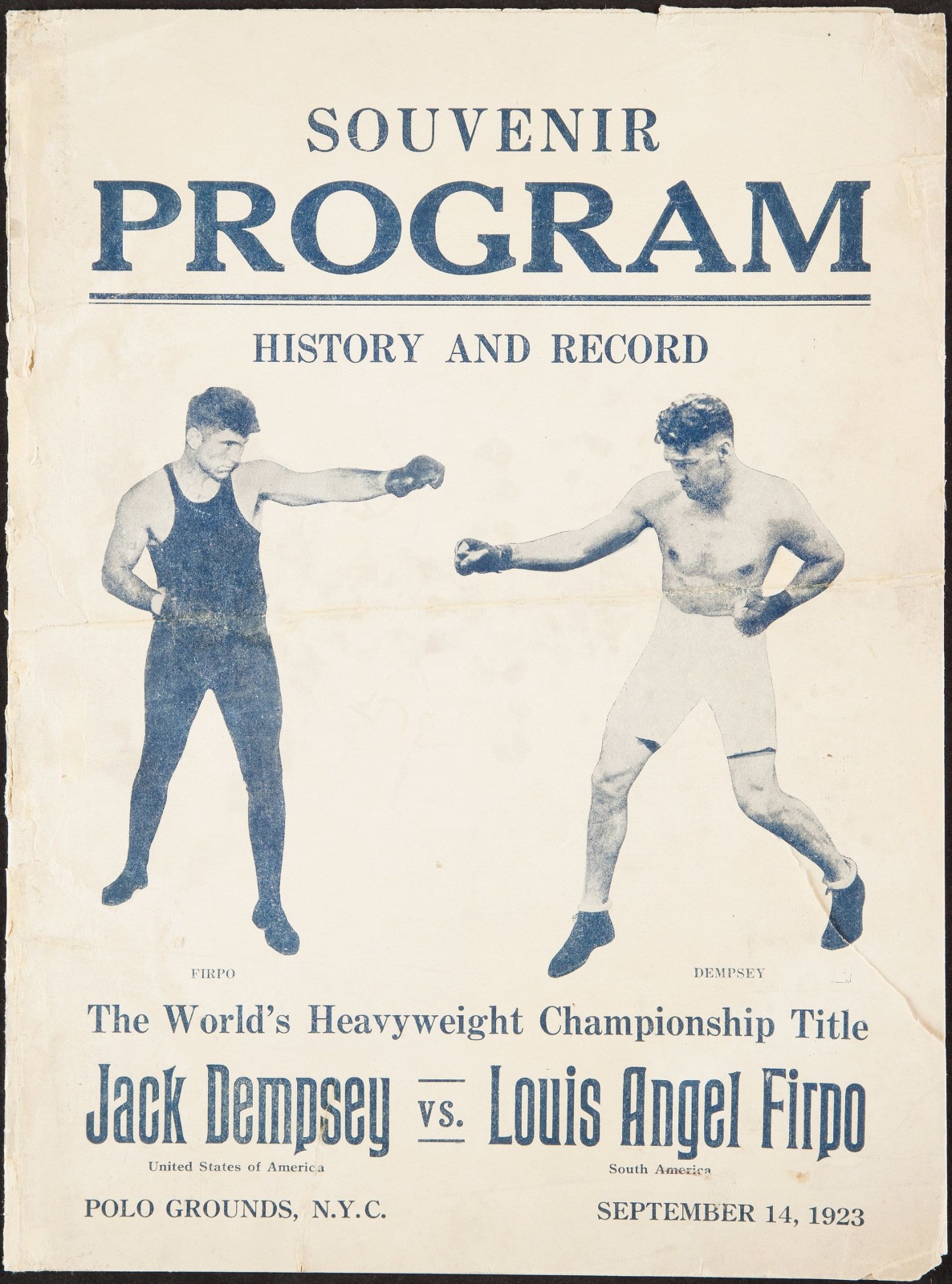

Although Kitaj adapted Bellows’ composition, the painting Dempsey and Firpo was not the subject of Kitaj’s painting. His multiple subjects were rather (1) the boxing match itself and (2) the libel case brought by James McNeill Whistler against the critic John Ruskin in 1878. When Whistler vs. Ruskin (Novella in Terre Verte, Yellow and Red) was selected by Kitaj for his 1994 Tate Gallery retrospective, he wrote a text that elaborated on both these themes. The fight between Jack Dempsey and Luis Firpo, held on 23 September 1923, concerned ‘the world’s heavyweight championship title’. In his conversational style, Kitaj commented:

What a fight that must have been—even Babe Ruth was there for the whole four minutes it lasted. I've followed boxing all my life and I've taken liberties with some of the strange events of those four minutes (it was Dempsey, the eventual winner, who was knocked out of the ring) […].

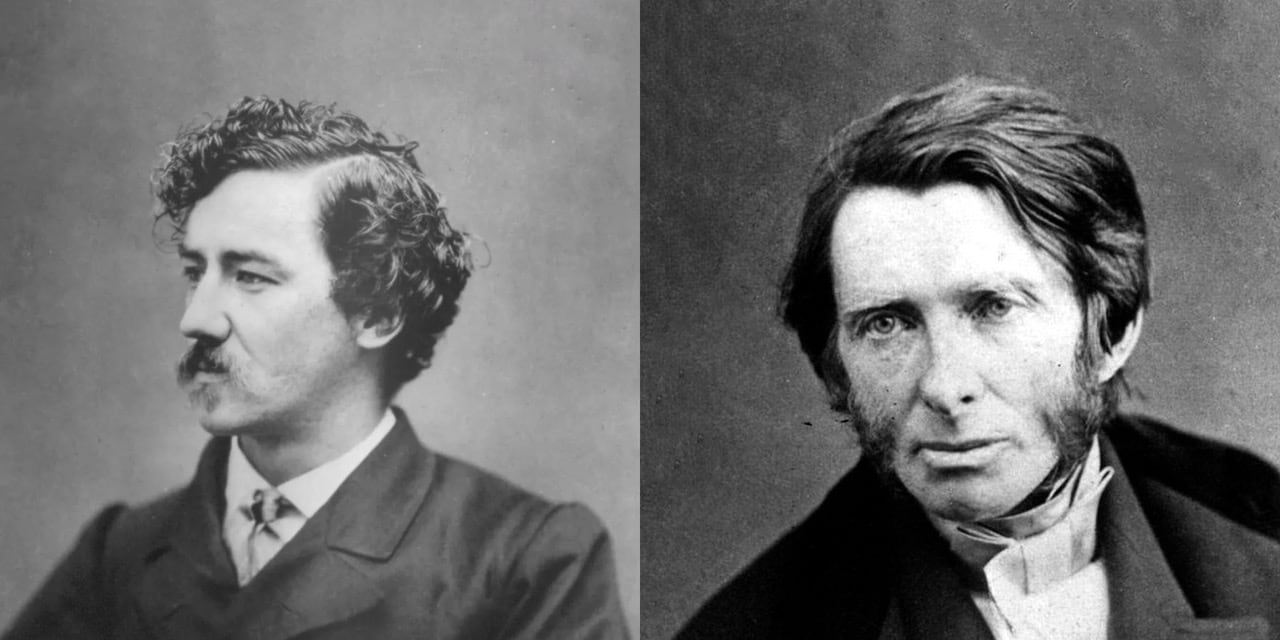

Just as he adapted the composition of Bellows’ painting, so too Kitaj used the memorable boxing match between Dempsey and Firpo as a carefully weighted metaphor for the libel case between Whistler—the litigious butterfly—and Ruskin—an eminent art critic turned reactionary, famed for his early defence of Turner’s work. The case was fought between ‘the Brush and the Pen’, as Whistler put it, and as Dante Gabriel Rossetti suggested, Whistler was no stranger to a fight: ‘A tube of white lead/ Or a punch on the head/ Come equally handy to Whistler.’ Referring to one of Whistler’s nocturnal firework paintings, exhibited in 1877 at the newly opened Grosvenor Gallery, Ruskin called the artist ‘a coxcomb’ and accused him of ‘flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face.’ Although the judge ruled that Ruskin’s remarks were indeed defamatory, he awarded token damages of just one farthing. Whistler was forced to sell his new house in Chelsea, so recently completed, owing to the ruinous legal costs, and to comfort himself with a pyrrhic victory.

The layers of Whistler vs. Ruskin (Novella in Terre Verte, Yellow and Red) include Kitaj’s indirect personal connections with both claimant and defendant. Like Whistler a long-time resident of Chelsea, Kitaj identified closely with him as an American abroad. Both men were ‘London American coxcombs’, or, as Kitaj put it another way, ‘ “foreigners” ’. A diminutive figure dubbed ‘little Whist’, the hunched silhouette of a man, quoted from the famous nocturne of old Battersea Bridge, was quoted in several of Kitaj’s paintings. Walter Sickert later lamented how Whistler ‘would so constantly leave his easel for his writing desk’, and this comment was echoed by some of Kitaj’s critics at the time of his Tate retrospective. As for Ruskin, he founded the eponymous art school at Oxford in 1865. Kitaj was an alumnus of that school.

Kitaj was talented with both ‘the Brush’ and ‘the Pen’. As a painter he felt a strong commonality with Whistler. But despite the fact that it is Whistler, not Ruskin, who delivers the triumphant left hook in Whistler vs. Ruskin (Novella in Terre Verte, Yellow and Red), Kitaj was uneasy about his compatriot’s creed of ‘art for art’s sake’. His own practice was one of accretion in which both styles and subjects were accumulated and combined with great freedom. (The flailing figure of Ruskin is an ‘upended’ quotation from yet another source—the figure of Christ descending from the Cross in a painting by Rembrandt.) The subtitle—‘Novella in Terre Verte, Yellow and Red’—is a witty pastiche of Whistler’s own formalistic titles in which portraits and landscapes became ‘arrangements’ or ‘nocturnes’ in grey, green, black, gold, and so on. Kitaj’s ambitions as a writer (or painter) of novellas are elaborated to colourful effect in his painting. But his ambivalent compulsion both to paint and to write is well summarised in the neutral red figure at the upper right-hand corner—‘the referee’, as he wrote, ‘which is a self-portrait’.

IMAGES

Souvenir programme for Jack Dempsey vs. Luis Firpo, 14 Sept. 1923

Photographs of James McNeill Whistler, 1885, and John Ruskin, 1850s

James McNeill Whistler, Nocturne in Black and Gold – The Falling Rocket, exhibited 1877, Detroit Institute of Arts

Rembrandt, The Descent from the Cross, 1633, Alte Pinakothek, Munich