Euphemia Lamb was a remarkable presence among the advanced artists of early twentieth-century London and Paris. She was transplanted from an inauspicious corner of Manchester to London in July 1905, and thereafter lived adventurously.

InSight No. 148

Jacob Epstein, Second Portrait of Euphemia Lamb, 1911

‘Her adventures were to lead her, in one guise or another, into many memoirs’, wrote the biographer Michael Holroyd. Born Annie Euphemia Forrest (1887–1957), she was better known as Nina for a time. She lived in the Greenheys area of south Manchester, a world apart from that of Henry Lamb—a medical student, son of the applied mathematician Sir Horace—who eloped with her to London in July 1905. She was there introduced to the lineaments of Bloomsbury, known to Henry through his brother Walter—a Cambridge student and friend of Clive Bell and Thoby Stephen among others. Thoby’s sister Virginia Stephen (later Woolf) wrote ambivalent letters about Nina, and Duncan Grant had a short-lived affair with her after she moved to Paris in 1907.

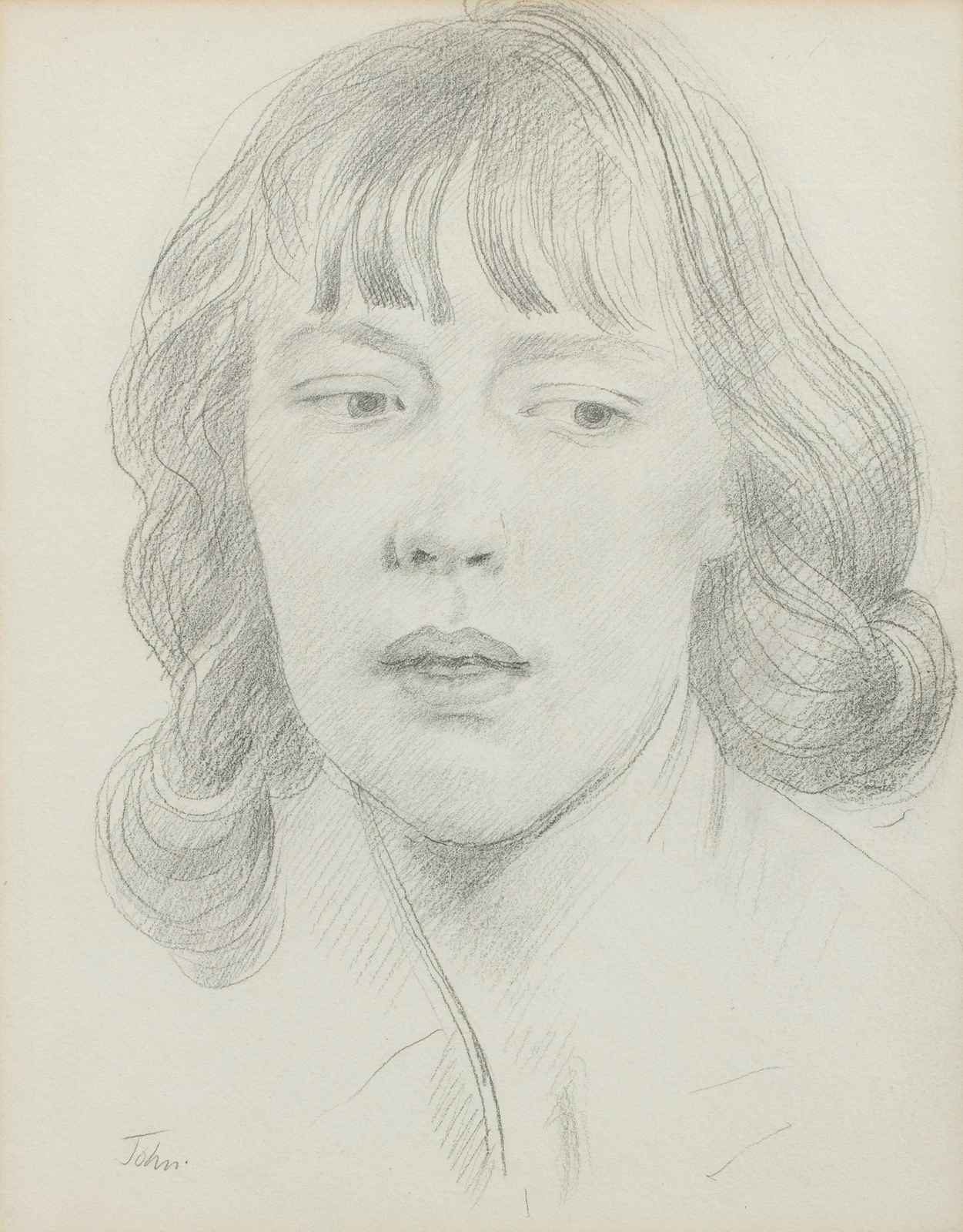

Her marriage to Henry Lamb on 10 May 1906 was prompted by her recently discovered pregnancy. By this time she was widely known as Euphemia, although Virginia and Duncan continued to know her as Nina. It was Lamb who renamed her, ‘since she reminded him so much of Mantegna’s Saint’. After suffering a miscarriage, her marriage to Lamb came apart and both partners became entangled elsewhere. While Augustus John admired her ‘pale oval face and heavy honey-coloured hair’, C.R.W. Nevinson thought her ‘a lovely ash blonde’. She was a muse to many artists and modelled frequently in the years before the First World War, each time being reinvented to suit the artistic needs of those she sat for.

In 1907, Euphemia modelled for ‘countless studies’ by John. These were mostly eloquent full-length pencil portraits, which show her wreathed in full-length dresses with heavy, dense skirts, sometimes elaborated with a sash. His full-face portrait of her has greater pathos and intimacy, and unusually depicts her with a fringe. John’s nickname for Euphemia was ‘Lobelia’, reflecting both a streak of Whitmanesque poetic whimsy and the intimate, even possessive nature of his relationship with her at the time. But it was a short-lived intimacy. In his autobiography Chiaroscuro, John mentioned her once only and then in relation to James Dickson Innes with whom she had a love affair—she was described there simply as ‘his Euphemia’.

In both John’s drawing and Epstein’s two portrait busts of Lamb, her mouth is open. In a memoir, Viva King wrote: ‘I fancy I can hear, through the open mouth, her ugly voice.’ She alienated some people—King amongst them perhaps—on account of her many sexual affairs. Her physical presence could be provoking, and she reportedly wore ‘no corset or underclothes’. She was remarkably free living for the times (John called her ‘eccentric’) and fostered insecurity in many wives and mistresses. Although her behaviour elicited varying degrees of opprobrium, she exercised considerable freedom at a time when most women monogamously connected to artists were freighted with domestic and childbearing duties. In a letter to Violet Dickinson written in April 1914, Virginia Woolf described Lamb with conflicting notes of admiration and distaste:

I think she is by this time a professional mistress. She has lived with various people. […] I believe she’s rather nice and pretty—but without any morals. […] I don’t think she’s wanting, and she certainly was amazingly pretty. I think she moved from person to person—I could write pages of her adventures, because she used to appear at intervals with amazing stories of her doings, which were partly invented, but I think she was very attractive to a good many people.

Epstein’s ‘second portrait’ of Lamb adapts the classical format of the portrait bust. The flat bottom of the bronze, shorn of the moulded plinth used in so many traditional busts, gives a sense of Epstein’s artistic projectile—moving away from conventional forms of working towards a more transgressive practice. The sensual quality of the sitter’s body is communicated: it is cropped to include the beginnings of her arms and her breasts, the latter partially concealed behind a strapless slip, adorned with a protruding angular bow. The modelling and detailing are naturalistic and vital, and the line of her shoulders and the curve of her back suggest a sense of Lamb’s posture. To treat a named sitter with such freedom was unusual. It suggests the complicity of the model and the artist—Lamb being indifferent towards social propriety on one hand, and Epstein pursuing his own distinctive artistic and erotic purposes on the other.

Notwithstanding narrow perceptions of her as an artist’s model and a ‘professional mistress’, Lamb was a remarkable personality who lived for more than having her likeness set down. She transcends the images of herself that survived her. Piano Nobile is displaying four portrayals of her—those by Epstein, John, Lamb and Innes illustrated here—in the exhibition Augustus John and the First Crisis of Brilliance, and together they invite consideration of her as a person, not merely a life model. She played a significant role in the broader culture of her time, a vivid character who contributed to the circumstances that enabled such searching and original art to be created.

Images:

Mantegna, St Euphemia, 1454, Museo nazionale di Capodimonte, Naples

Augustus John, Euphemia, c. 1907, Private Collection

Henry Lamb, Euphemia, 1906, Private Collection

James Dickson Innes, Euphemia Lamb, c. 1909–11, Private Collection

Installation photograph of Second Portrait of Euphemia Lamb