To coincide with the opening of Piano Nobile’s new exhibition Augustus John & the First Crisis of Brilliance, InSight considers the many personally and technically significant portrait drawings that John and his friends made of each other.

InSight No. 147

Augustus John, Portrait of Percy Wyndham Lewis, c. 1905

For those who attended the Slade School of Art during Henry Tonks’s tenure as Drawing Master, drawing from life was regarded as a hallowed skill. Referring to the ‘verve and style’ of drawings made at the school, D.S. MacColl wrote: ‘The hour of Rubens had returned’. In Tonks’s life classes, smudging and rubbing out were forbidden. Modelling in light and shade was to be achieved by line alone. Although many of the students also mastered painterly effects of ink and waxy red chalk and crayon, much of their graphic work demonstrates a highly inventive use of line. This is especially true of Augustus John (1878–1961), whose ‘prodigal sketching’ made him a talisman amongst his contemporaries. His work was inflected with a vivid and outrageous attitude to life—‘rebellious against the ordinary and scornful of the pretty’. Equipped with this outlook, he led a highly successful revolt against the stifling manners of the Victorian age.

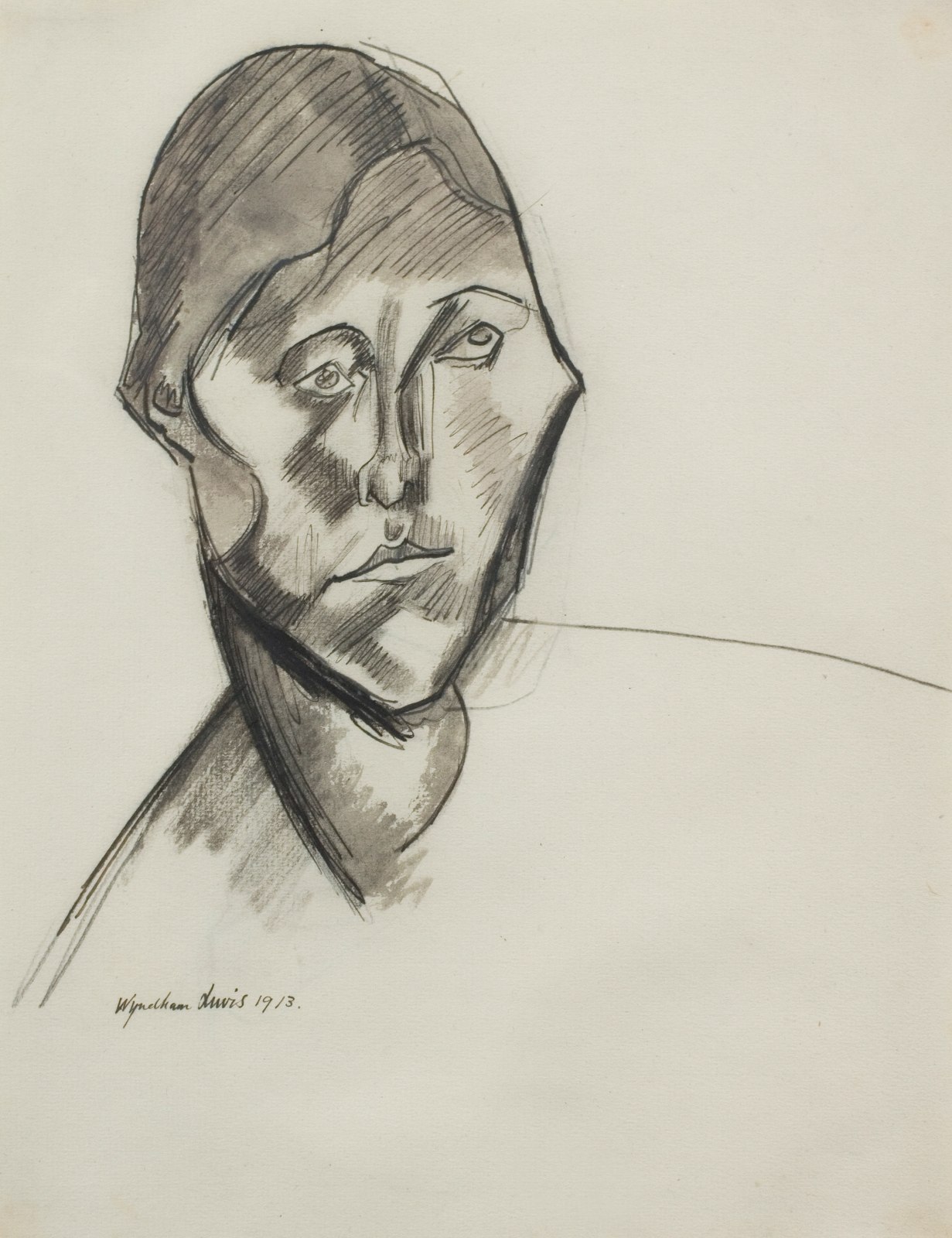

In his portrait study of Wyndham Lewis (1882–1957), one of several full-face drawings made with red chalk in a small notebook, John well suggested the brooding intensity of his young friend. Lewis himself arrived at the Slade in 1899, shortly after John left, and first set eyes on this ‘mythological figure’ when John paid a return visit to the school’s life room. Lewis was later described as ‘the best draughtsman at the Slade since John’. His Portrait of Helen Saunders, made in 1913, applied a new cubistic idiom in which the sitter’s features were aggressively formalised by exaggeration and simplification. Yet the drawing, notwithstanding self-conscious modifications, bears a strong family resemblance to a more traditional kind of draughtsmanship: the head-and-shoulders portrait in graphic media perfected by Augustus John. Lewis’s model, herself briefly in attendance at the Slade and now recognised as a gifted experimental abstract artist, is touched by a sense of vitality, her brows arched and her gaze glazed but life-like.

It is no coincidence that so many portrait drawings from this milieu of artists involved men depicting women. The likes of Ida Nettleship, Edna Waugh, Gwen Salmond, Mary Spencer-Edwards and Helen Saunders at first sought careers as artists, undertaking the same rigorous training as John, Lewis and others, before the intricately connected demands of marriage and life modelling laid claim to their time and energy. Among a generation of so many promising female artists, Gwen John alone produced a significant oeuvre.

Many Slade students of the nineties were depicted by Augustus John in refined draughtsmanship that well suggests attitudes of the time. John’s portrait drawing of Mary Spencer-Edwards is a model of sophisticated fin-de-siècle elegance, complete with a bombastically extravagant hat. The sitter’s gaze is strangely abstracted and her fingers are spread absent-mindedly on the arm of her chair. Such an image of stillness and inaction answered the society’s expectations for a woman of her class, notwithstanding the sitter’s proficiency as an artist. She later married another Slade student, Ambrose McEvoy, and only began exhibiting again after his premature death in 1927.

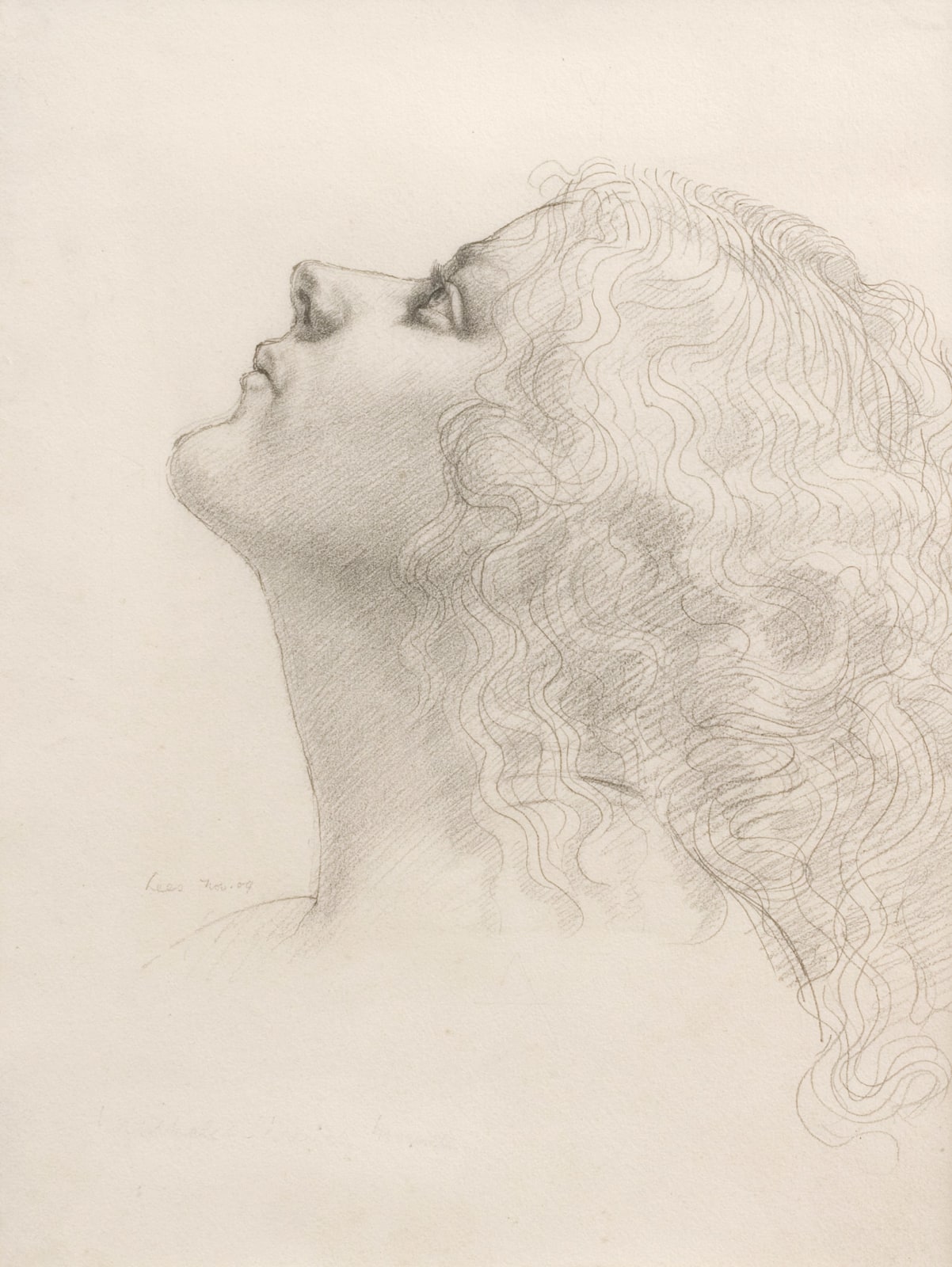

Other women who came into John’s circle felt destined for a life in art, but as muses rather than makers. They were required to have not merely serene self-possession but also extraordinary physical resilience. Edith Price, also known as Edith Ashley or Lyndra, most recognisable by her prominent rounded jawline, modelled for John in the guise that came to distinguish his drawings of full-length female figures in the years leading up to the First World War. In one drawing she wears a full-skirted dress, her hair is loosely tied back, the gestures are declamatory—one arm akimbo, the other holding up the skirts—and her feet are bare. She later married Derwent Lees, another Slade proficient whose talents won him the position of Assistant Drawing Master when he graduated in 1907. His drawings of her are marked by an animation and linear precision similar to John’s.

Technical excellence in drawing enabled objectively accurate qualities of likeness and modelling. But objective accuracy often served the urgent, subjective need to represent a sitter—often a lover, a friend, a sparring partner. The refined system of line drawing taught at the Slade came to be closely connected with the deportment, dress and social presence of those who modelled for John and his friends. When viewed together as an ensemble, these portrait drawings suggest a social gathering. To stand amongst them is to enter a milieu of ardent, talented people.

Images

Percy Wyndham Lewis, Portrait of Helen Saunders, 1913, Private Collection

Augustus John, Dorelia, 1909, Private Collection

Augustus John, Portrait of Miss Spencer-Edwards, c. 1899, red chalk on paper, 30.5 x 24.1 cm

Derwent Lees, Lyndra, 1909, graphite pencil on paper, 33 x 24.8 cm

Augustus John, Edith Lees, c. 1910, graphite pencil on paper, 39.5 x 20 cm

Installation photograph of Augustus John & the First Crisis of Brilliance