In the art of Frank Auerbach, reassuring continuities—of studios, sitters, idiom—are pitched against the desperate struggle to do it differently each time.

InSight No. 144

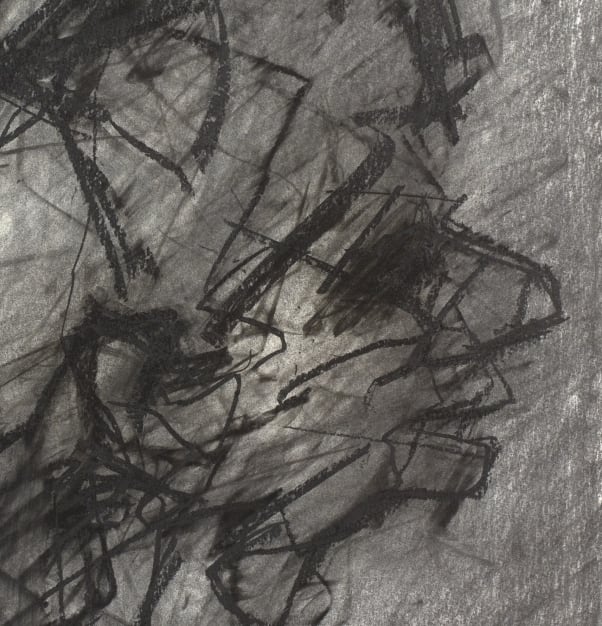

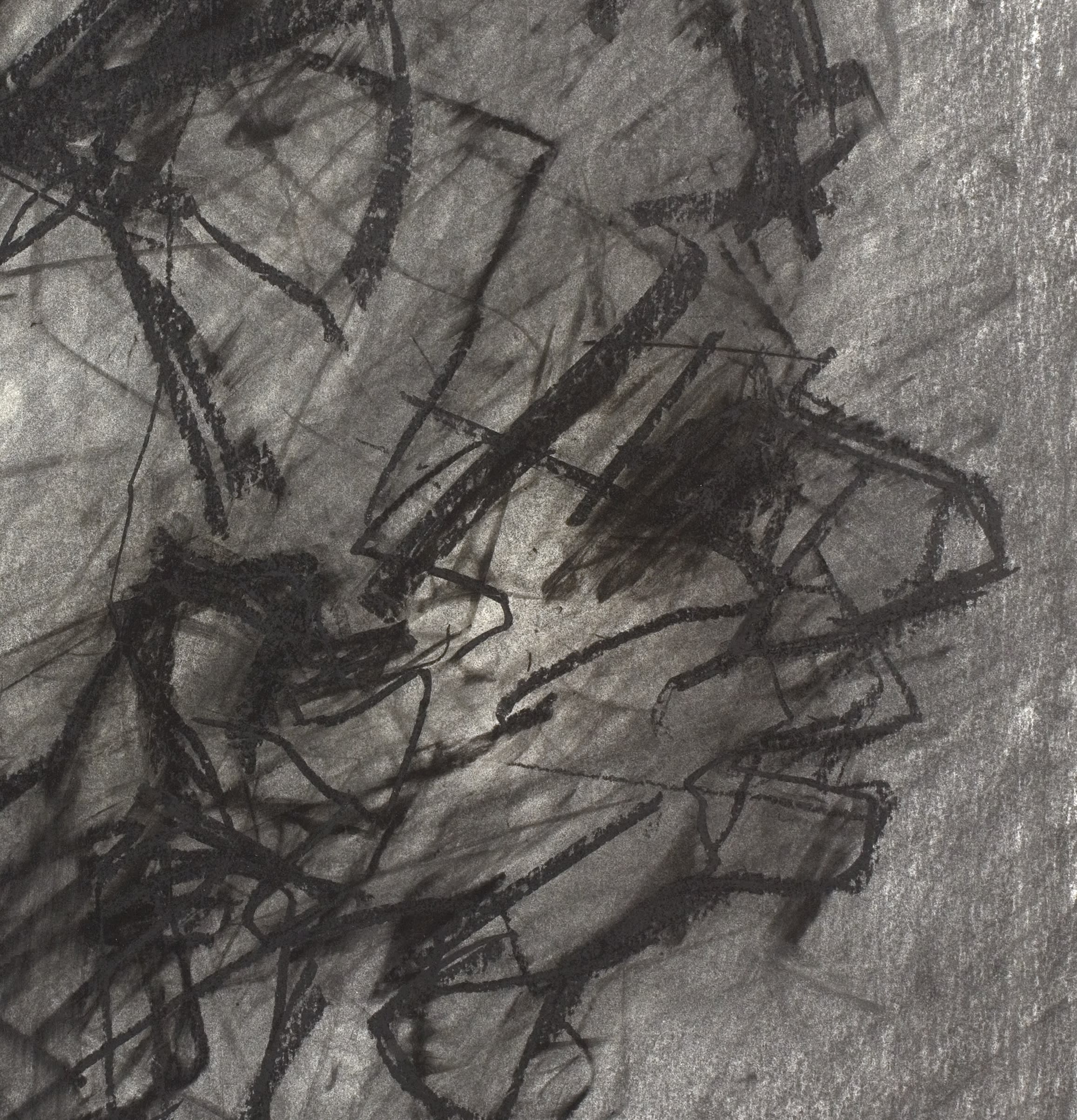

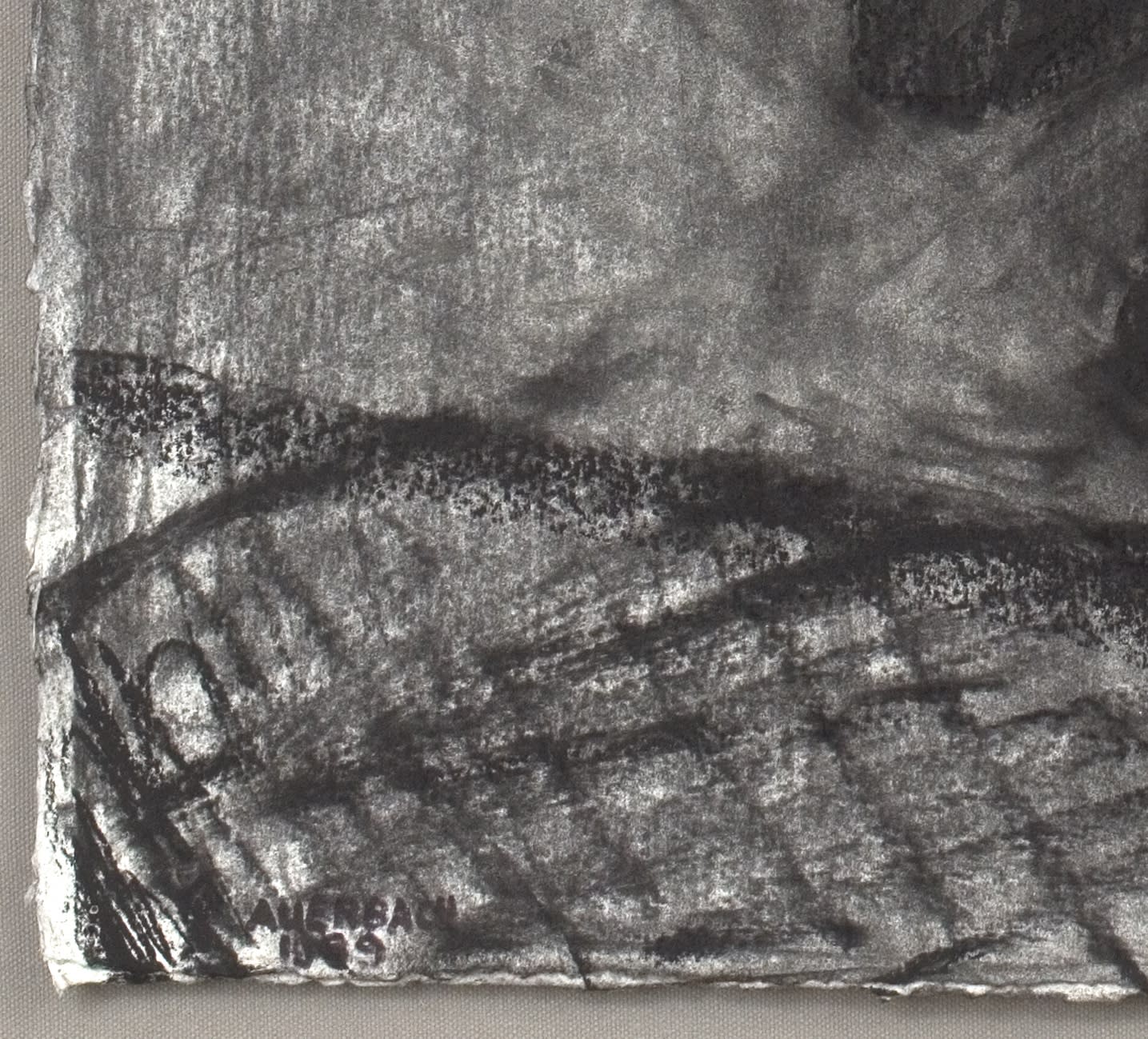

Frank Auerbach, Head of Julia - Profile II, 1989

In the thick of a creative struggle, Frank Auerbach (b. 1931) is only dimly aware of patterns emerging from picture to picture. He has often worked continuously from a small number of sitters and his compositions tend to shift in small gradations (or not at all) from one picture to the next. Two or three pictures, sometimes more, will explore a certain composition—the head viewed from behind in a three-quarter-length view, or frontally, or bowed forward, or tipped back—before the urge to ‘make it new’ reasserts itself, new visual insights generate new positions and emphases, and a dramatically different approach is adopted in the next few pictures. Taken together as a linear sequence from one picture to the next, Auerbach’s oeuvre can be loosely plotted in terms of such cyclical patterns of continuity and rupture.

This process is illustrated by two charcoal drawings of Auerbach’s wife Julia made in 1989. Head of Julia – Profile and Head of Julia – Profile II view the sitter from the same position and in the same attitude: her head is seen in profile and she looks to the right. The second drawing differs from the first in certain features: it magnifies the head to fill more of the sheet, with less negative space around the edges; Julia’s shoulder is draped in an area of widely spaced hatching. But these differences are fractional in comparison to the seismic formal shifts in Auerbach’s work from year to year and decade to decade.

Speaking to Richard Cork in 1988, Auerbach explained the element of continuity in his practice:

By the time I’ve finished [a painting], there are so many sensations left over, so many possibilities I haven’t explored, that finishing the painting actually impels me to try to do another one – to excavate the subject further or to pin it down more exactly, or to use left-over sensations that one hasn’t been able to express in the picture that one’s just finished.

To complete a picture, Auerbach imposes upon himself the need to discover a ‘new fact’. An unfailingly self-critical nature has permitted him to continue seeing more and more over long periods spent with the same models. Ageing brings about changes in a sitter, and this has in part provided Auerbach with new material and inspiration when working with the same individuals over weekly two-hour sessions. The longer he spends with a sitter, the richer his sense of them as a subject, the more pictures he is compelled to make.

In Head of Julia – Profile and Head of Julia – Profile II, although their every mark is placed differently, the evocation of the subject is remarkably uniform between them. There is the same precise suggestion of the visible cheek bone, the ripple of sinews in her neck, the weight of piled-up hair. A deep familiarity was evidently needed for Auerbach to complete these works: only a detailed visual conception of his subject could permit the creation of two such similar, such differently constructed pictures. Both drawings map out the same image, the same phenomenal imprint, using an entirely different set of marks. Unlike most pictorial artists in art history, he does not develop codified, repeatable schema. Rather, through an unspecified number of erased rehearsals—the residue of which underlies and reiterates the final image—Auerbach deepens his sense of the sitter’s physical presence until he can realise it in a final feverish effort.

Auerbach became interested in profile views in the later nineteen-eighties. From the mid-sixties and for twenty years or so, he had used the ‘reclining head’ as a motif by which to represent a sitter’s head in especially unfamiliar and strange pictorial configurations: ‘The whole point of having a model in front of you is that it continually surprises one’, he has said. Then around 1987, he began exploring the unfamiliarity and strangeness of the profile. He immediately made a cycle of five sequentially numbered paintings entitled Head of J.Y.M. – Profile. To a heightened degree, these and subsequent ‘profile’ paintings and drawings abrogate human sensibility in favour of literal shapeliness, the mechanical torsion of the head connecting with the neck, jarring recessions and lunges across the face and around the ‘lump’ of the whole head, the ‘flag-like’ quality of the head as a flattened outline on a coloured background. In these works the focal point is usually the tip of the nose, emphatically beak-like and sharply delineated.

Auerbach’s remarkably static lifestyle has permitted his pictorial interests to shape his work, unlike those who make the mistake of moving around too much. In 1983, he wrote to his friend R.B. Kitaj—then sojourning in Paris—‘suggesting that there have been very few good peripatetic artists’. Yet Auerbach’s own life has involved some change, as when he took a second studio in Finsbury Park in 1987 and subsequently worked there in acrylic rather than oils. Julia sat for him forever thereafter in Finsbury Park, and this is where the two Head of Julia – Profile drawings were made. Finsbury Park is not so far from his first studio in Mornington Crescent, however, and Auerbach is an outstanding example of his own rule that ‘very good artists’ tend to stay put.

Images

1. Frank Auerbach, Head of Julia - Profile II, 1989, charcoal on paper, 30 x 22 in

2. Frank Auerbach, Head of Julia - Profile, 1989, Private Collection © The Artist

3. Head of Julia – Profile II (detail)

4. Head of Julia – Profile II (detail)

5. Frank Auerbach, E.O.W.'s Reclining Head, 1969, Private Collection © The Artist

6. Frank Auerbach, Head of J.Y.M. - Profile V, 1987, Private Collection © The Artist