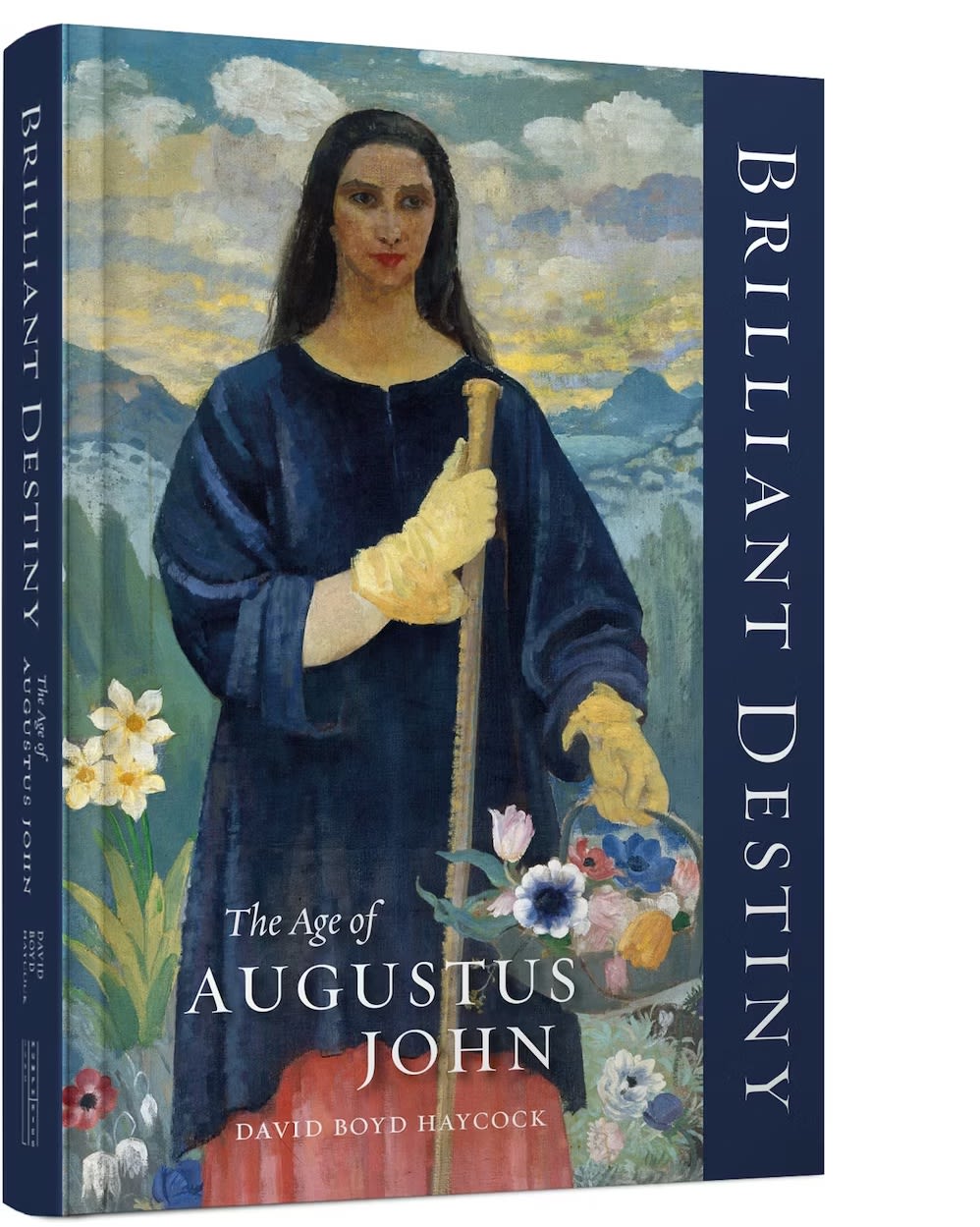

The archetypal muse, Dorelia McNeill inspired some of Augustus John’s most sensitive portraits in painting and drawing. One writer described how John intended to make of her ‘a modern Mona Lisa’.

InSight No. 131

Augustus John, Portrait of Dorelia, circa 1905

Augustus John (1878–1961) was an artist of extraordinary facility and a character of prodigious vitality. In a typically wry account, Kenneth Clark described the sudden emergence of his genius:

The legend began with that famous episode, John’s dive. He had been a silent, conscientious and, by all accounts, talented member of the Slade School. Then, in the summer holidays of 1897, he hit his head on a rock so violently that he tore half the scalp from his head. He recovered miraculously but slowly, fretting at a long convalescence which seemed like an imprisonment. When he returned to the Slade his fellow-students saw an entirely different man. He was no longer quiet, industrious and unremarkable; he was violent, daring and exceptional.

As the archetypal bohemian artist, he was also an archetypal chauvinist. He preferred his sexual partners to be several years younger than himself, some were vulnerable, most had “alluring” looks and figures, and few of them lasted in his affections.

Against this background of used and discarded women, Dorothy McNeill (1881–1969) stood apart as an unmarried partner of John’s who held his attention, captured his imagination and frequently thwarted his demands. Only the bond with his wife Ida was comparably deep. Dorothy was better known as Dorelia, her nicknames included ‘Dodo’ and ‘Ardor’, and their relationship endured until John’s death. In Brilliant Destiny, a new monograph about the young Augustus John published last month, David Boyd Haycock described the inception of John and McNeill’s relationship:

The regular flow of his domestic life was about to take an extraordinary new turn. It was his sister who introduced him to the woman who would change the course of his life. […] At a party in London, Gwen met a beautiful and rather enigmatic young woman who soon became the subject of another of her intense infatuations. Born in south London in 1881 into a large, lower middle-class family, Dorothy McNeill was an intelligent, quiet and darkly attractive 21-year-old typist in a City law firm. She was taking evening classes at the Westminster School of Art and lived in a basement flat in Fitzroy Street, not far from the Johns. When Augustus met her sometime in late 1902 or early 1903, he fell immediately in love.

After their meeting McNeill eventually came to join John’s household, which already included his wife Ida. An amicable ménage à trois was established, and this lasted until Ida’s premature death following the birth of her fifth child in 1907. McNeill herself gave birth to four of his children and more than once induced a miscarriage – a significant reclamation of agency from John’s uncompromising virility. She was one of his most constant sitters, modelling for a large number of paintings and drawings, and ‘his projection of her’, wrote art historian Keith Clements, ‘is still one of the most famous images in British painting’. Amongst those works of John’s to sell at auction, the highest prices have consistently been achieved by depictions – many of them drawings – of McNeill and her sister Edie.

John’s sister the painter Gwen John also developed ‘a strong attachment for’ McNeill, in the words of art historian Emmanuel Cooper. She made several portraits of her, including Dorelia in a Black Dress, which was painted during their fêted escapade to Rome in 1903 – a journey that began in earnest when they left the boat at Bordeaux and terminated prematurely in Toulouse. They apparently drew and sang for money and slept by night in the fields or stables, ‘lying on each other to feel a little warmer’, Holroyd noted, and living on ‘old bread, new cheese and middle-aged figs’, Clark wrote.

In the early forties, when John and McNeill’s life had settled somewhat, the prospect of a knighthood loomed for Augustus. However, the Palace became concerned when it discovered that the couple were not in fact married. It was suggested they did so. John proposed and Dorelia demurred. As John’s biographer Michael Holroyd put it: ‘She had no wish to be known as “Lady John”.’ So the knighthood fell through.

Notwithstanding the strength of her will, like other muses before her Dorelia became a ‘projection’ of those who sought her. She left little record of her outlook. Holroyd was occasionally puzzled by her motives, noting that ‘she seldom revealed her thoughts’, and she was an enigma to many of those who met her. In Portrait of Dorelia, a red chalk study from the early years of the twentieth century, she looks askance with a quick glance. It is John’s remastered, revitalised handling of a Renaissance staple – the naturalistic single-head life study as practised by Raphael, Michelangelo and so many others. She appears swathed to the neck in homemade, gypsy-inspired dress, and her hat is flowing and informal, the brim casting a shadow over her eyes. The dramatic chiaroscuro throws the delicate arch of her nose into relief, and the brightest highlight on her lower lip is registered by the unmarked whiteness of the paper. The ambiguous characterisation is underpinned by a vivid sense of human presence, conjured with the most exacting, inventively minimal use of chalk marks, which have been applied with a variety of sharply detailed finesse and gently smudged shading. Drawings such as this give force to the critic D.S. MacColl’s claim that John ‘scattered broadcast drawings with a wild flame of life in them.’

Images:

1. Augustus John, Portrait of Dorelia, circa 1905, red chalk on paper, 18.5 x 12.5 cm

2. Lady Ottoline Morrell, Emily Chadbourne, Dorelia McNeill and Augustus John, May 1909, possibly photographed by Philip Morrell © National Portrait Gallery, London

3. David Boyd Haycock’s new book Brilliant Destiny: The Age of Augustus John (2023, Lund Humphries)

4. Augustus John, Portrait of Dorelia, circa 1904, Private Collection

5. Gwen John, Dorelia in a Black Dress, circa 1903–4, Tate

6. Michelangelo, Study of a Man's Head, 1508–12, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

7. Portrait of Dorelia (framed)