To mark the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Good Friday Agreement, InSight considers the Irish artist William Crozier’s Figure in Landscape – a profound painting touching on life, death, and the Troubles.

InSight No. 122

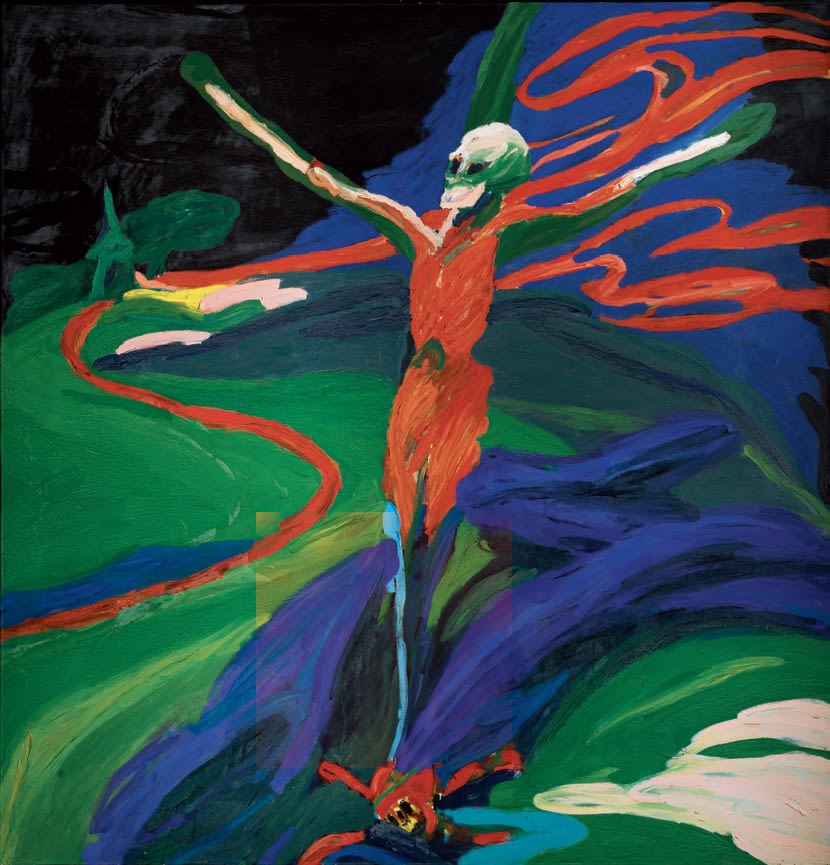

William Crozier, Figure in Landscape, circa 1972

On 10 April 1998, the Belfast Agreement was signed by political leaders from the UK and the Republic of Ireland. The text of the agreement acknowledged the tragedies of the past while looking forward to ‘a new beginning’, offering solutions to fundamental issues of sovereignty, policing and reconciliation. It was the key moment of the peace process in Northern Ireland, which brought an end to three decades of sustained sectarian violence between unionists and republicans. The Troubles affected everyone on the island of Ireland and in Britain, and the agreement was endorsed by a large majority both in Northern Ireland and in the Republic, who expressed their support in a referendum held on 22 May 1998.

William Crozier (1930–2011) was deeply involved with Ireland before, during and after the Troubles. His familiarity with the country and his empathy with its culture came through his paternal family from Country Antrim, who had emigrated to Glasgow. Although he was born in Scotland and lived in England for much of his professional life, Crozier’s sense of his Irish inheritance led him to adopt Irish citizenship at the height of the Troubles in 1973 – a public expression of his strong connection to the country. He subsequently acquired a property in West Cork in 1983 and became ‘a much-loved Irish painter’, as IMMA’s director Sarah Glennie described him in 2017. But in the early seventies, when he lived in London, Crozier’s view of the Troubles was at once that of an external observer, looking on from across the Irish Sea, and a disturbed participant, profoundly affected by the violent irruptions in a greater Celtic culture to which he belonged.

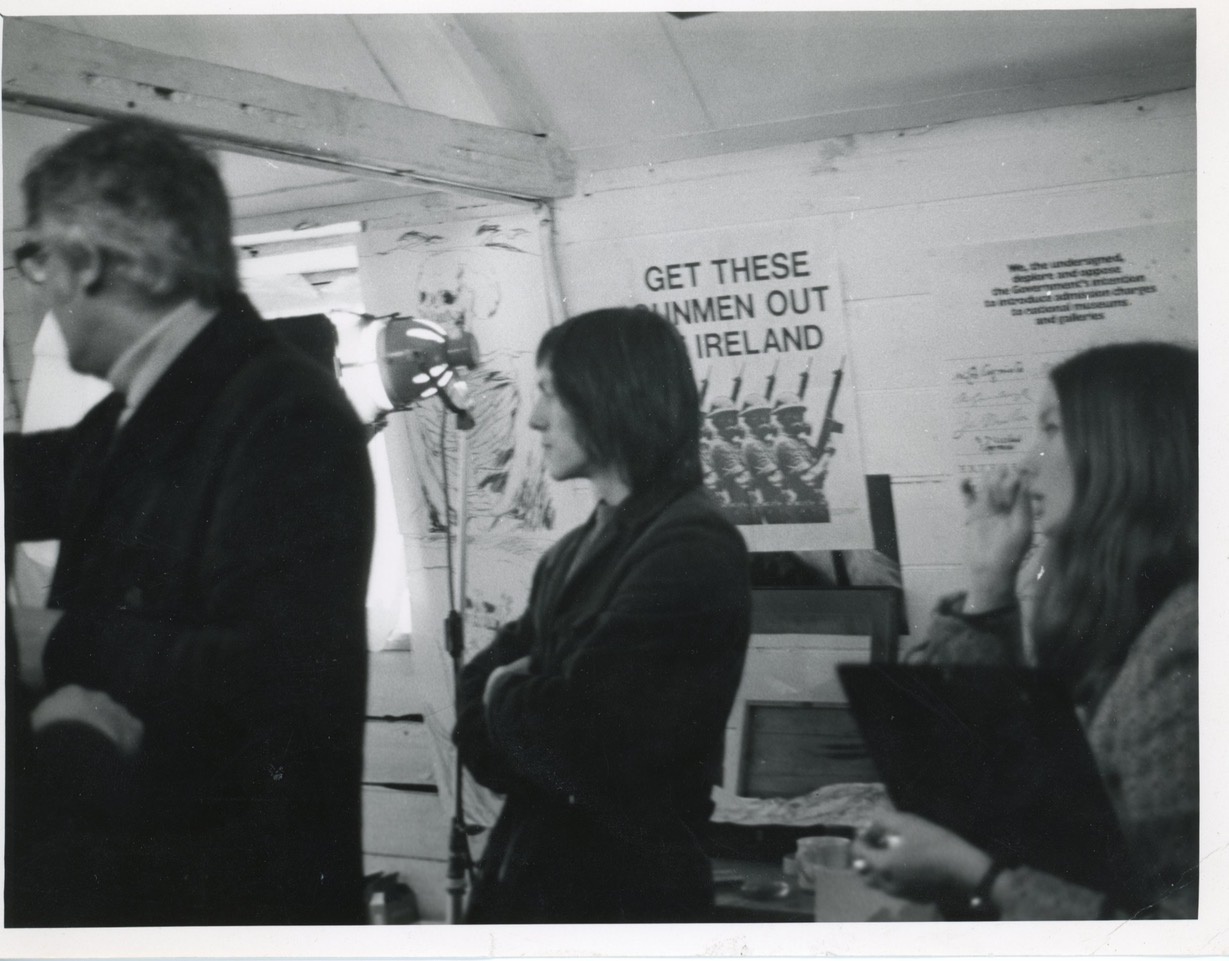

Crozier was a life-long pacifist and did not publicly align himself with either the unionist or republican cause. Nevertheless, his London studio was adorned for a time by posters expressing indignation at the presence of British Army soldiers on the streets of Northern Ireland. The slogan ‘GET THESE GUNMEN OUT OF IRELAND’ was a rallying cry among republicans, but also found a sympathetic reception among those such as Crozier who regarded with dismay the aggressive presence and concomitant violence of professional soldiers in civilian areas.

Figure in Landscape depicts an animated skeleton figure ensconced in a landscape of ambiguous proportions. A lightning bolt of red rainbow slices downward across a cloud of ultramarine blue at the upper right-hand corner, a rippling motion answered all over the painting by similar arcing shapes – not least in the pulled back knees of the figure, which shimmer and bleed into the surroundings. A darkened, ink-like stream issues from the figure, trickling downward from left to right. Areas of opaque colour – a narrow strip of yellow at the right-hand edge, strokes of red and green at the lower edge – are contrasted with thin, dry sweeps of the brush. Colour seems to be conditioned by the rainbow optics of dispersion, with each colour registering distinctly and in sharp contrast to neighbouring areas. Although the palette is wild and exaggerated, the painting is underpinned by the naturalistic shape of clouds, hills and streams. A tree at the upper left-hand corner is depicted with a fine outline in green paint, but there are no place-specific landscape markers: the fulgent colouring and amorphous terrain are sustained by the agonised skeletal figure and belong to it, either sharing its emaciated state of existence or helping to draw out the poison that afflicts it. As in the landscapes of Chaïm Soutine, emotions quiver in a zone beyond the reach of language.

A variety of reference points cluster around Crozier’s depictions of a skeleton in the landscape. While a painting such as Crossmaglen Crucifixion uses overtly Christian imagery, others make less specific connections to memento mori, a fear of nuclear holocaust, and the murder of Jews in concentration camps like Bergen-Belsen, which Crozier had visited in 1969. It is a reflection of Crozier’s artistic integrity that no single reference is transparent, and his imagery of the human skeleton continues to be allusive and richly coded. Amongst these references, however, the Troubles must be counted as one of the most pertinent and contemporary. Figure in Landscape was made at a time of significant violence in Northern Ireland. Nearly five-hundred individuals including victims of the Bloody Sunday shootings were killed in 1972 – the worst year in the conflict.

Much as Ulysses was written in Zurich, Trieste and Paris, notwithstanding its preoccupation with the street life of Dublin, Crozier’s landscape art pertains to Ireland but was made between studios in southern England and West Cork. Cultural separation was the condition needed for reflection in both cases. With Figure in Landscape, Crozier rummaged in the closet of his psyche and produced a skeleton with no simple meaning: it was at once monstrous and compassionate, baring its wounds but pointing a way to reconciliation with mortality and greater awareness of life’s preciousness. As the anniversary of the Belfast Agreement approaches next week, Crozier’s art offers a poignant reminder of both what was lost in conflict and what has been regained since that ‘new beginning’.

Images:

1. William Crozier, Figure in Landscape, circa 1972, oil on canvas, 172 x 172 cm

2. William Crozier's studio, 1970, photographed by the artist © The Estate of William Crozier

3. Figure in Landscape (detail)

4. Chaïm Soutine, Le Village, circa 1923, Musée de l'Orangerie, Paris © RMN-Grand Palais / Hervé Lewandowski

5. William Crozier, Crossmaglen Crucifixion, 1975, Private Collection © The Estate of William Crozier