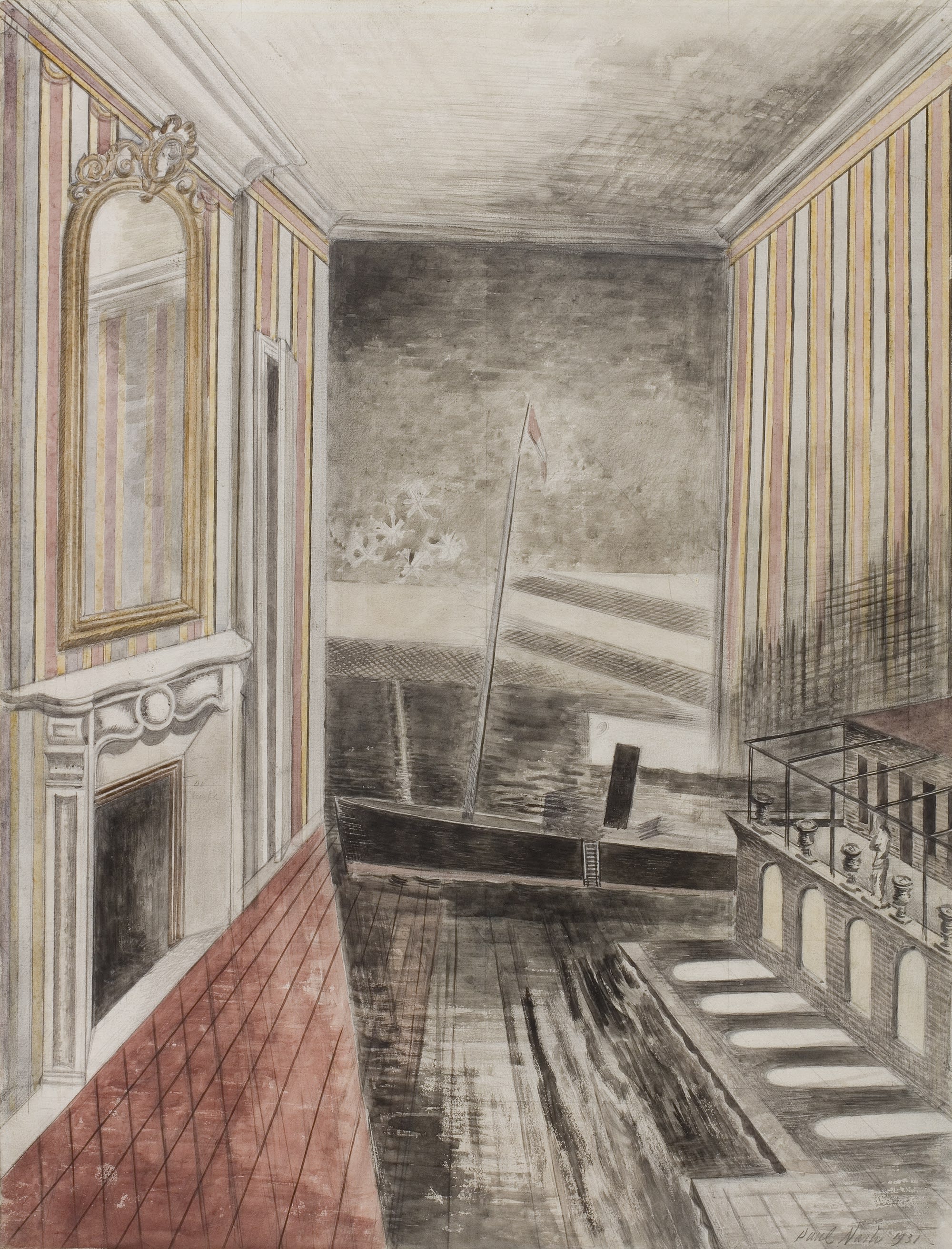

Darkest night enters an enclosed room. Dreams and the hinterland between waking and sleeping underlie Paul Nash’s surrealist masterpiece, which is now showing in Piano Nobile’s exhibition Drawn to Paper.

InSight No. 121

Paul Nash, Harbour and Room, 1931

Surrealism gave western art a mechanism for accommodating vivid fantasies within naturalistic imagery. René Magritte gave equivalence to pictures and their real-life subjects, and sometimes brought a landscape inside through a doorway or window. Paul Delvaux populated uncanny streets and arcades with women in varying states of undress. In Salvador Dalí’s dreamscapes, flowers hatched from eggs and clock faces melted on withered tree branches. This caustic, often deranged art was driven by the discomfort of a generation of artists, variously recovering from distress suffered during the Great War or in life more generally, and all striving for an art that would extract a response from indifferent or desensitised audiences. Some years after the first surrealist manifestos were published in 1924, the recovering war artist Paul Nash (1889–1946) entered the field with his own personally significant bricolage of fantasy and naturalism.

Harbour and Room shows a hotel room in which the back wall has disappeared. The inky waters of the harbour without are beginning to edge their way across the floorboards. Nash’s characteristic dry brush watercolour technique allowed him to achieve great detail – the fussy mouldings of a stone fireplace, a statue on the harbour redolent of Giorgio de Chirico’s – while the medium’s transparency facilitated the atmospheric rendering of the night sky, the liquid surface of the harbour, and the shallow tide that creeps over the long wooden boards. The picture’s strange fascination grows from the dissonance of an enclosed space, quotidian with sharply delineated furnishings, meeting the expanse of the wide world outside – the grand arcade of the portside architecture, drastically shrunken in its proportions, and the warship with its high foremast.

The shoreline is a well-established literary metaphor for the liminal space between waking and sleeping, living and dying, fixity and motion. In Richard II Bolingbroke bids ‘sweet soil, adieu’, and in Powell and Pressberger’s motion picture A Matter of Life and Death David Niven’s airman cheats death and washes up on a beach in Norfolk. Nash’s imagery in Harbour and Room grows from the same rich earth. His residency at Dymchurch, Kent, brought him close to the edge, as well as introducing him to the American writer Conrad Aiken, who lived nearby at Rye. Shortly before Harbour and Room was painted, Aiken wrote of:

[…] the double law

Of life and death; life and death;

Dust and breath; dust and breath.

Reflections of this kind contributed to Nash’s poetic imagination in the early thirties, and Harbour and Room exploits the period’s troubled preoccupation with sleep, dreaming, death and grief. Whereas today such troubles are readily characterised as symptoms of post-traumatic stress, at the time they were a motor for creatives such as Aiken and Nash.

Harbour and Room exists in two versions – a watercolour and an oil painting. The watercolour came first. A recently uncovered inscription on the reverse matches the date inscribed at the lower right-hand corner, 1931, although the eminent Nash specialist Andrew Causey suggested that it may have been started in 1930. Completed several years later in 1936 and almost a replica of the watercolour, the oil painting was owned for many years by the surrealist impresario Edward James, who was famed among other things for his remarkable home, Monkton House, an idyllic Lutyens design latterly converted into a green and lilac oasis with carved fibreglass palm trees and a stairway carpet imprinted with disembodied footprints. After James’s death his executors sold Harbour and Room to the Tate. It can currently be found hanging in Tate Modern, staking a claim for Nash’s place in the modernist movement.

Shortly before he made Harbour and Room, Nash had passed through Paris and was interested by the contemporary art he saw at Léonce Rosenberg’s gallery, including works by de Chirico, Max Ernst, Amédée Ozenfant and Gino Severini. However, although the oil version of Harbour and Room was included in the 1936 International Surrealist Exhibition in London, Nash did not subscribe to many tenets of the surrealist creed and held himself apart from the collective. He was altogether uninterested in the movement’s political ambitions. Writing in The Listener in 1931, he referred to ‘the dangerous charms of Surrealism’.

The imagery of Harbour and Room was inspired by a large mirror in the artist’s room at the Hôtel du Port along Quai Cronstadt in Toulon, where he and his wife Margaret stayed in early 1930. Nash was disconsolate to his friend Percy Withers about the town’s ‘bad or indifferent cooking’ and the rigmarole of ‘hunting hungrily up and down smelly streets for new cheap restaurants which weren’t too nasty’.

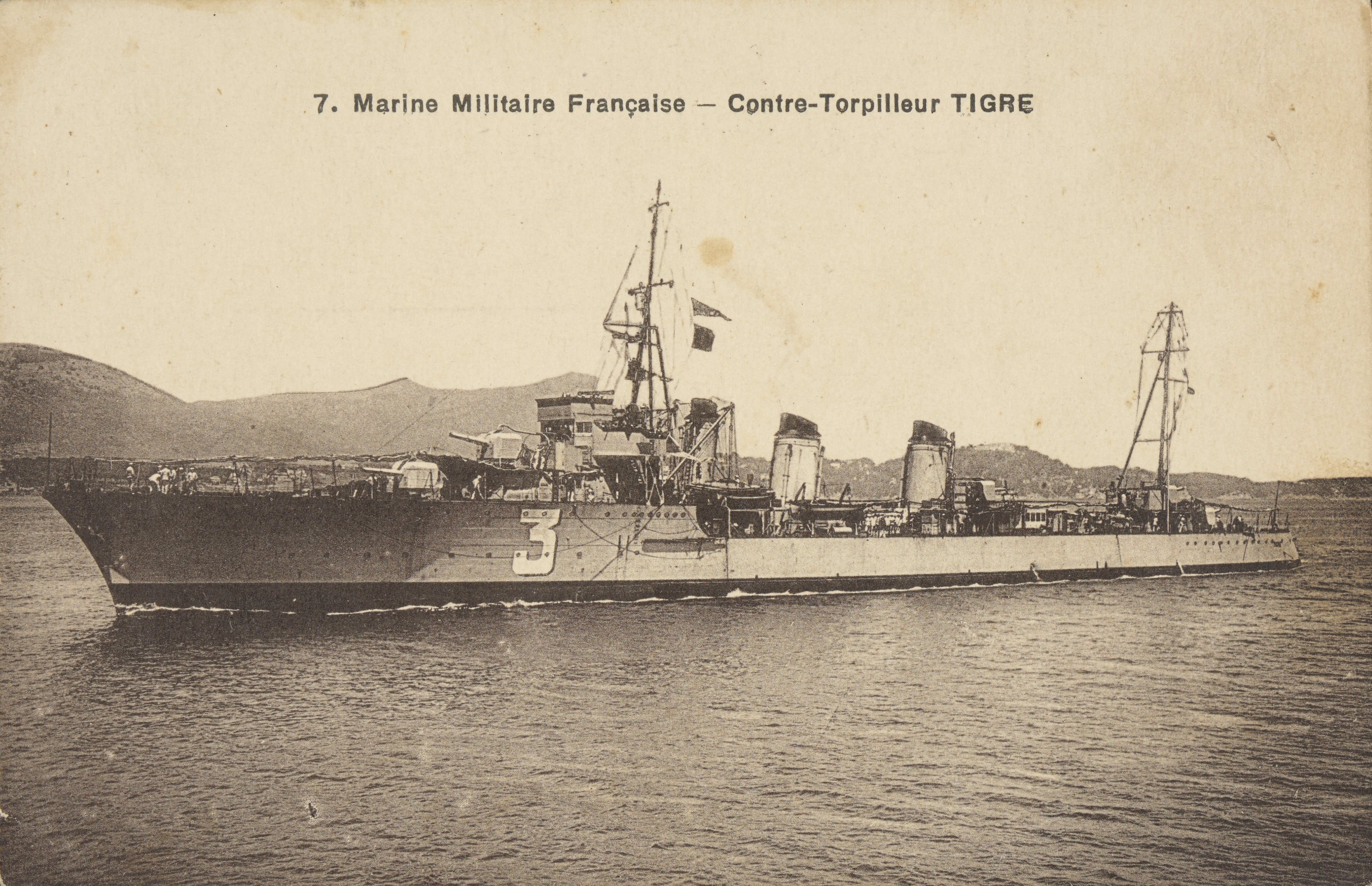

More auspiciously, Toulon was home to the French navy. (It was later the site of a strategically significant scuttling in 1942, in which seventy-seven vessels were destroyed.) The coming and going of destroyers gave Nash’s visual imagination pause for thought during their stay at the Hôtel du Port. As he wrote to Withers, ‘I drew valiantly from my window every day, baffled and desperate in my ignorance, tangled up in unsuitable rigging, bewildered yet fascinated by the strange architecture of ships.’ Margaret later described Harbour and Room as:

[…] to my mind a very beautiful picture, depicting a French Man o’ War sailing into our bedroom; the idea resulting from the reflection of one of the ships in the very large mirror which hung in front of our bed.

This ‘very beautiful picture’, perhaps the high point of Nash’s engagement with surrealism, was the product of long and careful study. Causey records the existence of eight sheets from a sketchbook used by the artist in Toulon. These studies are mostly squared for transfer, and the watercolour Harbour and Room is underpinned by a pencil-drawn latticework of vertical, horizontal and diagonal lines, which allowed the transposition of various components into a single coherent space. In Harbour and Room and many other pictures by Nash, this kind of sound technique and craftsmanship intersects with a numinous poetic vision. The result is a profound art that resonates with the timbre of its period.

Images:

1. Paul Nash, Harbour and Room, 1931, watercolour and pencil on paper, 51.5 x 39 cm

2. David Niven washed up in A Matter of Life and Death (1946, directed by Powell and Pressburger)

3. Paul Nash, Harbour and Room, 1932–36, Tate Collection

4. The staircase at Monkton House, West Sussex © Charles Holland

5. The Tigre, a French destroyer stationed at Toulon in the twenties and thirties

6. An RAF photograph of Toulon harbour after the scuttling in November 1942

7. Paul Nash, The Fleet at Toulon No. 1, 1930, Private Collection

8. Harbour and Room