For many people, a trip to the Sussex coast is a holiday. Piano Nobile’s new exhibition Jean Cooke: Seascapes & Chalk Caves shows that for Cooke, it was vital to her life as a painter.

InSight No. 120

Jean Cooke, Seven Sisters, 1992

At the age of thirteen, Cooke (1927–2008) travelled with her family from Lewisham to Sussex under duress of war. Anticipating the Blitz, they went to live near the coast in the village of East Dean, a locus amoenus of flint-built cottages just a mile inland from the sea at Birling Gap. Cooke formed a lasting attachment to the place and when the war was over she moved by herself to live in nearby Seaford, where she ran a pottery workshop making toys and ceramics. Business was bad, however, and she was forced to supplement her income by picking winkles off the beach. After returning to London and training at the Royal College of Art between 1953 and 1955, she eventually made her way back to the Sussex coast.

The coastline between Seaford and Eastbourne was a special concern of hers. Just beyond the historic cinque port of Seaford lies the Cuckmere Valley, famous for its winding estuary. Beyond that sheer chalk cliffs – the Seven Sisters – run along to Birling Gap, where an area of coombe rock – a mixture of chalk, flint and clay silt – has caused dramatic erosion far greater than that affecting the neighbouring chalk. To the east lies another famous chalk cliff, Beachy Head. It was here that she began making art in the mid-sixties, exhibiting works called ‘Cave (Birling Gap)’, ‘Beachy Head’, ‘Downs’ and ‘Seaford’ in her 1967 solo exhibition at the Lane Gallery, Bradford. Cooke responded to this landscape, and after making regular holidays there she began renting one of the former coastguard cottages at Birling Gap in the early seventies.

From there she could look out to sea and become engrossed in her surroundings. Speaking to her friend the playwright Nell Dunn in 1986, Cooke explained:

I had an obsession building up with this landscape in Sussex. I need to go back (whether the children like it or not) and just paint. I think about it a lot. But it isn’t only landscape; I also get possessed by people when I’m painting them. With landscape paintings, the wind’s always blowing, the light’s changing, the tide’s going in or out […].

She went on, saying: ‘I love the beach because it’s so clean – washed twice a day.’ When coastal erosion brought the sea dangerously close in 1995, forcing the demolition of her cottage, Cooke was outraged and distressed. She was undeterred, however, and soon afterwards purchased the neighbouring cottage. ‘That will see me out’, she said – and it did. It too was demolished, but not until after her death in 2008.

In the catalogue to accompany Piano Nobile’s exhibition, the curator Jane Alison has discussed Cooke and her work in the context of ecofeminism. Alison suggests that the artist’s situation enabled the art she made:

It was here on the cliff edge, or in her overgrown garden among the cherry blossoms and doves at her gloriously shambolic London abode in Blackheath, that Cooke could be at one with nature. She could be herself, a free spirit. […] With any one of her four children, David, Jason, Dayan and the youngest, Wendy, she blended in seamlessly with her surroundings. Painting on the beach or in her cave, windswept and dogged, she must have been part of [Birling Gap’s] attraction.

To live in Birling Gap was not merely a convenience, connecting the artist to an inexhaustible pictorial resource, but a vocation. For several months of the year, typically through the summer, Cooke lived there because her raison d’être was to absorb the place and depict it truthfully.

To date Cooke’s public profile has largely rested on her frank, sometimes painfully honest self-portraits and portraits of her one-time husband John Bratby. The most startling of these shows her bruised from Bratby’s acts of domestic violence. When some of these works were exhibited in the Barbican’s Postwar Modern exhibition in 2022, the critic Adrian Searle took them to show that Cooke was ‘a far better painter’ than Bratby. But these works do not reveal the full range of Cooke’s ability, a further key aspect of her artistic identity being a sensibility for this particular coastal environment. Jean Cooke: Seascapes & Chalk Caves shows she was not just an astute painter of people but an imaginative painter of landscape, uniquely attuned to the shifting conditions of life at the cliff’s edge.

Images:

1. Jean Cooke, Seven Sisters, 1992, oil on canvas, 45.1 x 54.6 cm

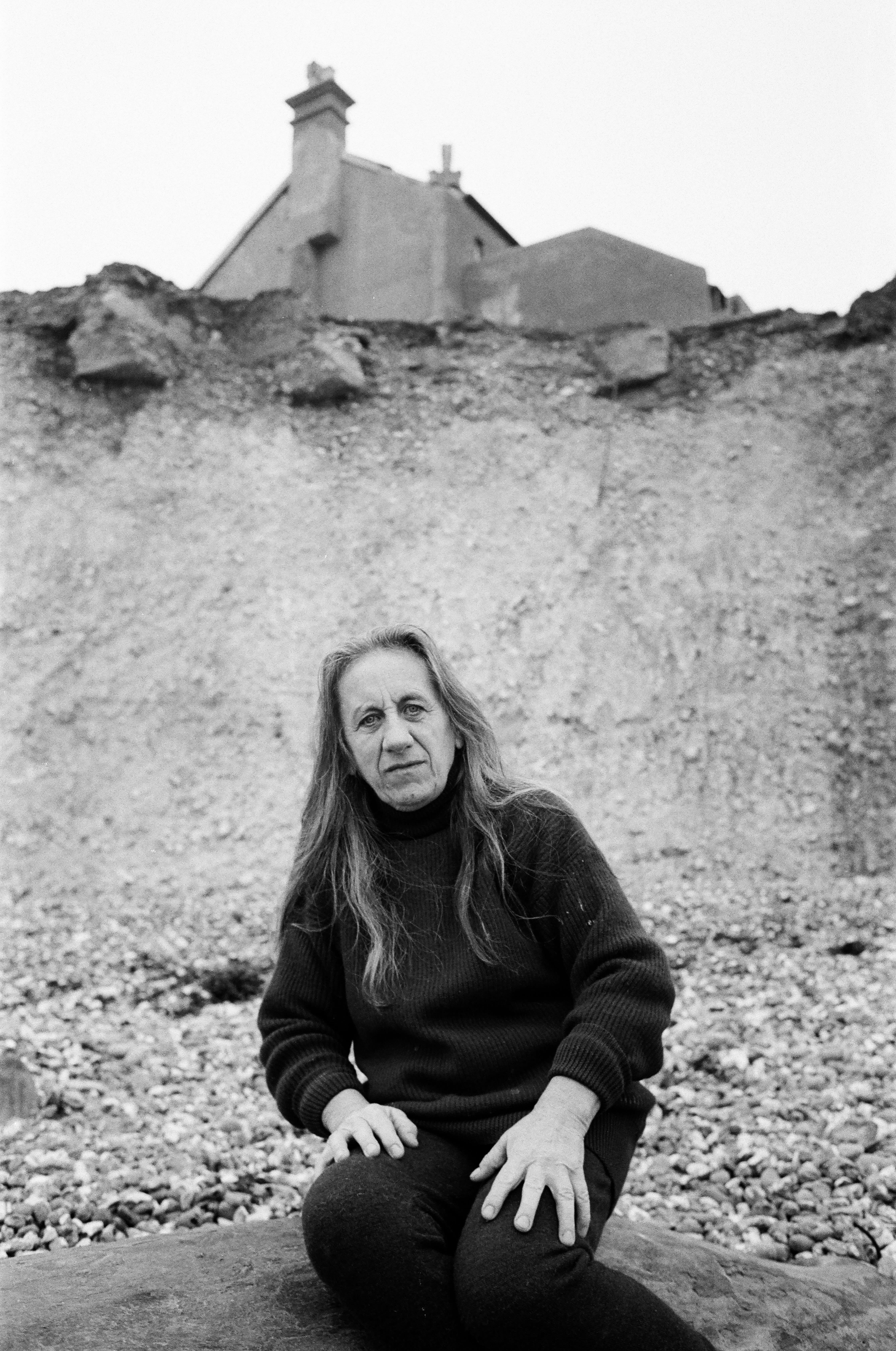

2. Jean Cooke at Birling Gap, circa 1995, photographed by her friend Linda Sole © Linda Sole

3. Jean Cooke, Cave Painting, 1965, oil on panel, 28.6 x 27.9 cm

4. Installation shot of Piano Nobile’s exhibition Jean Cooke: Seascapes & Chalk Caves

5. The beach at Birling Gap, circa 1975, photographed by Jean Cooke

6. Installation shot of Piano Nobile’s exhibition Jean Cooke: Seascapes & Chalk Caves

7. Jean Cooke, Verde, Verde, circa 1980, oil on hardboard, 32 x 37 cm