Paul Nash was a poet painter whose landscape paintings evince a hidden world, overflowing with Blakean imagery and fragmentary historical remains.

InSight No. 112

Ruin in the Forest of Dean, 1946

Paul Nash (1889-1946) was a modernist advocate of Horace's dictum 'ut pictura poesis': as in painting, so too in poetry. Nurtured by his reading of English poet artists such as William Blake and his connections with contemporary visionary writers such as H.J. Massingham, Nash did not simply paint the landscape as he found it but transfigured it through the prism of imagination. In his 1942 monograph British Romantic Artists, John Piper situated Nash's work in an unbroken tradition leading from Blake, Constable and Turner through to the nascent neo-romantic art of his own generation. But Nash was a progenitor of neo-romanticism rather than a participant, and his work was highly individualistic. In pictures such as Ruin in the Forest of Dean he composed scenes that did not literally depict a specific place. An element of fantasy was often at work, whether in the excavation of some imagined past or the playful combination of anachronistic features.

One of the visionaries in Nash’s circle of friends was the ‘ruralist’ writer H.J. Massingham. In the preface to his book The Tree of Life, published in 1941, Massingham wrote:

I have no doubt in my mind that a powerful new movement is stirring, though as yet unsure of itself, towards a reconciliation between the religious and the organic views of life, and it comes both from the Churches and the ruralists. We earth-men need the sanction of religion for our efforts to rediscover the true England [...].

Although Nash may not have identified himself as an ‘earth-man’, like Massingham he took a profound and sometimes spiritual view of life. A streak of idealism animated Nash’s thinking and fostered in his pictures of the English landscape a sense of peace, hope and emotional renewal.

Ruin in the Forest of Dean was inspired by a visit to another of Nash’s free-thinking friends, Clare Neilson. She and her husband Charles lived at a house called Madams in Gloucestershire, where Nash stayed in the nineteen thirties and forties (see InSight 105). On one of his visits to Madams he went to explore the Forest of Dean nearby, and at that time Nash took a photograph that later served as the source for his ‘Ruin’ watercolour of 1946. As his health began to fail in the 1940s, Nash was kept at arm’s length from his landscape motifs and increasingly used his back catalogue of photographs as a starting point for his pictures. A comparison of the watercolour Ruin in the Forest of Dean and a related photograph shows how the source image was cropped and elaborated upon, with a hilly landscape and atmospheric fair weather clouds added at the right-hand side, and the drystone wall at the left-hand side of the photograph omitted.

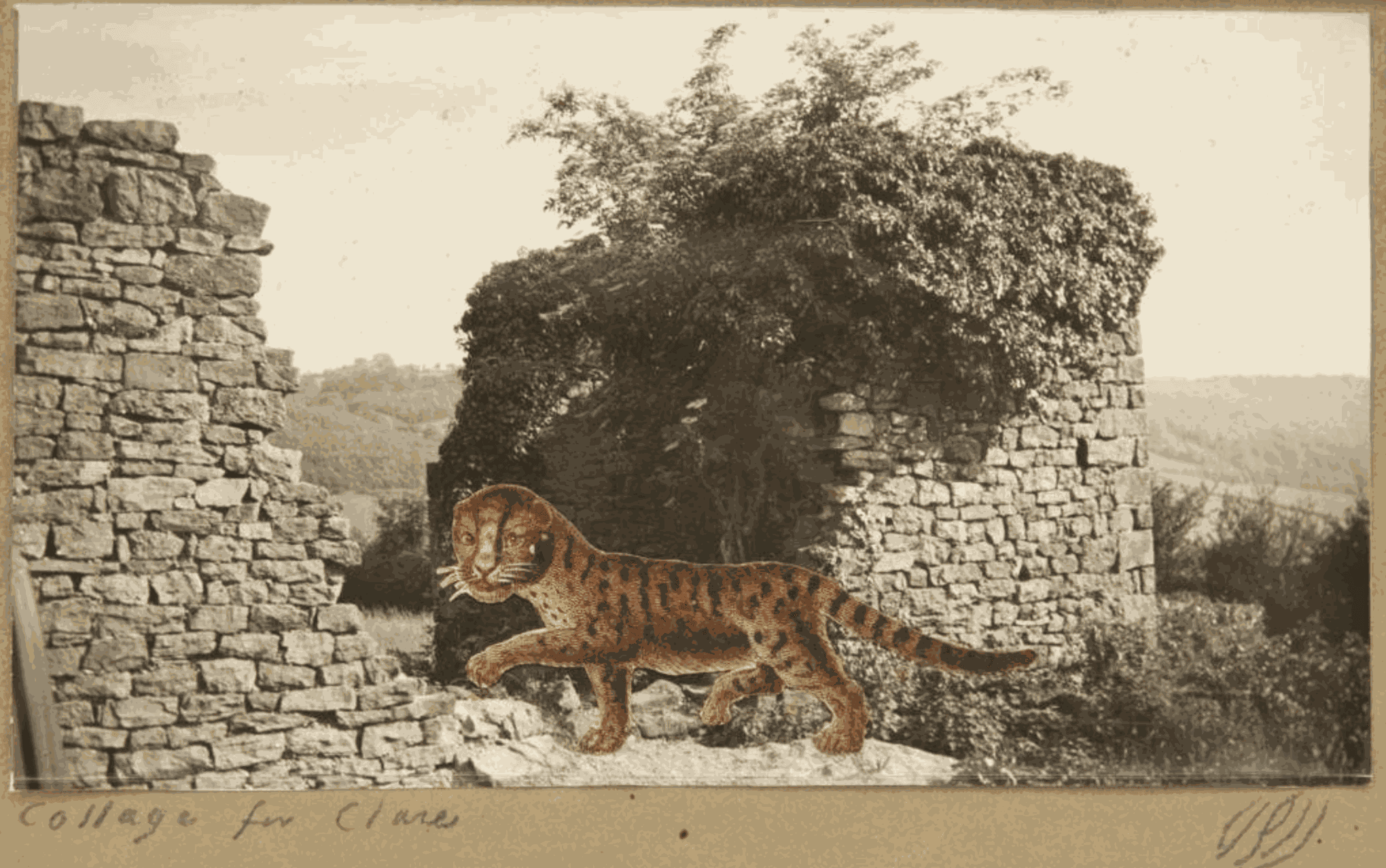

Some of Clare Neilson’s collection, including many prints, photographs and items of ephemera relating to Nash, is now owned by Pallant House Gallery, Chichester, having been donated by her godson Jeremy Greenwood in 2013. Amongst her papers is a print of Nash’s photograph showing a ruined structure in the Forest of Dean, transformed by the collaged addition of a colour-engraved tiger, who seems to be making his way into the decrepit structure. This collage is entitled Tyger, Tyger.

Nash’s poetic sensibilities were in sympathy with those of William Blake, and the collage’s title evokes Blake’s eponymous poem, the opening and closing stanzas of which are famous:

Tyger Tyger, burning bright,

In the forests of the night;

What immortal hand or eye,

Could frame thy fearful symmetry?

Nash was captivated by the ruins he found in the Forest of Dean – remnants of the iron and steel industries that sprang up in the eighteenth century and were largely derelict by the early twentieth. For him and his friends, the Forest was a place of imaginative fancy and one that answered Blake’s ‘forests of the night’. Nash wrote in a letter to Clare Neilson: ‘I am sure nothing would be less surprising in that queer part of the world than that a tiger should come out of the forest and eat his way through a stone wall.’ In Ruin in the Forest of Dean, Nash painted a landscape loaded with narrative possibility, historical undertones and poetic mood.

Images:

1. Paul Nash, Ruin in the Forest of Dean, pencil and watercolour, 18 x 25.5 | For Sale

2. Paul Nash, 1930s, photographed by Lance Sieveking, National Portrait Gallery © National Portrait Gallery

3. Paul Nash, dust jacket for Remembrance: An Autobiography by H.J. Massingham, 1941, Victoria & Albert Museum

4. Paul Nash, A stone wall and overgrown structure in the Forest of Dean, 1938, Tate Gallery Archive

5. Paul Nash, Tyger, Tyger, circa 1938, Pallant House Gallery, Chichester

6. William Blake, ‘The Tyger’, plate 42 from Songs of Experience, printed circa 1824, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

7. Framed image of Paul Nash, Ruin in the Forest of Dean, pencil and watercolour, 18 x 25.5 | For Sale