In the 1950s, the Slade School of Fine Art fostered a new generation of figure painters. Long hours in the life room instilled in these artists a lasting desire to interrogate the real thing – the human body – from close quarters at first hand.

Euan Uglow

Seated Nude, circa 1954

Unlike the dramatic poses of yesteryear, the Slade life room of the 1950s typically involved more naturalistic attitudes. Quite often a female figure was seated in a chair or on a stool, her arms held at her sides or her hands clasped together in her lap, her figure sometimes slumped and sometimes poised. The gestures were chosen by a tutor. Students drew straws to determine their position in the room, though conniving students like Euan Uglow (1932–2000) developed ways to cheat and gain their preferred spot. As Craigie Aitchison later explained, in the life room, ‘what they taught was all to do with getting the marks in the right place. It wasn’t to do with painting a mouth or an eye, it was putting a mark on a canvas in the right place as an equivalent to a mouth or an eye.’

During William Coldstream’s tenure as Professor of Fine Art between 1949 and 1975, the Slade enjoyed a renewal of creative spirits (see InSight 26). There was a moment of especially intense activity in the early 1950s when many young men returned from national service to mix with a younger generation. Three nudes painted by three different students – Uglow, Craigie Aitchison, Michael Andrews – show the opportunities for artistic experiment which Slade students discovered in the life room format at the time.

Uglow’s painting shows a woman seated in a three-quarter-length pose, her eyes heavy-lidded and her expression impassive. A folding screen is present at her back and the work was most likely executed while Uglow was still studying at the Slade, shortly before he graduated in 1954. The figure is modelled in substantial, panel-like areas of naturalistic skin tones. The heightened sense of naturalism is belied by the careful construction, however, with areas of modelling delimited by measuring marks which form an armature of dark outlines and dots. These criss-cross the torso, appearing around the breasts and collar bone, providing a wiry structure in relation to which the lively, rounded, three-dimensional forms are constructed.

Uglow’s close friend Craigie Aitchison also portrayed his seated model in a three-quarter-length pose. As in all three of these nudes, Aitchison’s figure is evoked using a narrow, highly refined palette of skin tones. Unlike the other two, however, the canvas glows with thinned out, scrubbed in colour: a spectrum of green, blue and pink hues surround the figure and blur its silhouette. Andrews’ treatment is cool and open-grained by contrast. As in Uglow’s painting, the vague background of the room is freely brushed and offers a compositional framework against which the main figure looms forward.

Beyond the life room, the female nude continued to be a source of fascination throughout Uglow’s career. It brought together purely artistic concerns – a legacy of classical tradition, the academic challenge of achieving verisimilitude – with a thrilling undertow of eroticism. The precise mixture of these elements invested Uglow’s nude paintings with an unfailing ambivalence and a tension between form and content which continues to intrigue.

Images:

1. Euan Uglow, Seated Nude, circa 1954, oil on board, 55.3 x 40.4 cm | For Sale

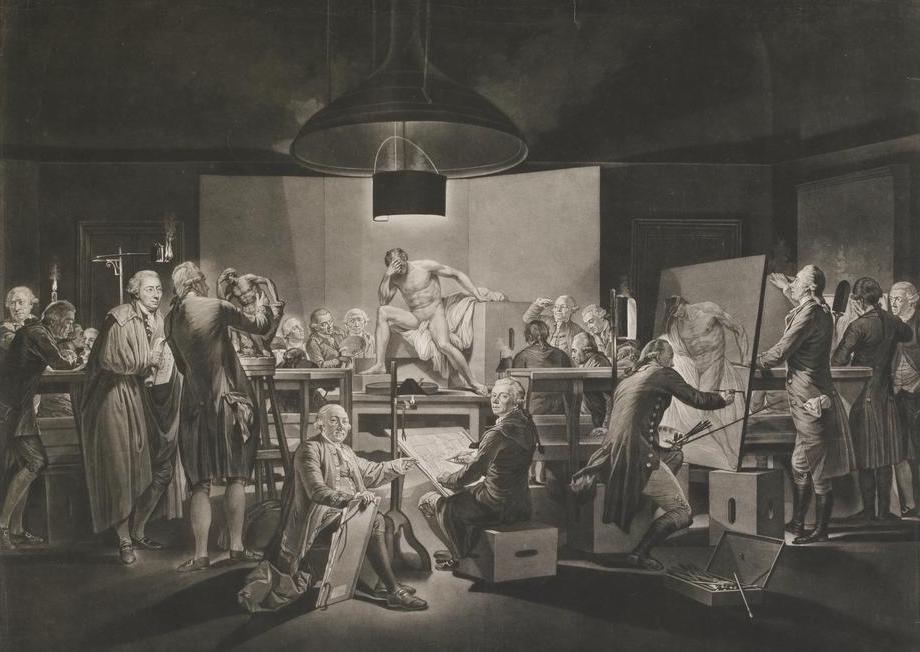

2. Johann Jacobé after Martin Ferdinand Quadal, La Salle du modèle de l'Academie Imp Roy des Beaux Arts à Vienne, 1790, British Museum © Trustees of the British Museum

3. Seated Nude (detail)

4. Craigie Aitchison, Nude, 1954, Private Collection

5. Michael Andrews, Seated Nude, 1952, Private Collection © The Estate of Michael Andrews

6. Euan Uglow, Curled Nude on a Stool, 1982-83, Ferens Art Gallery, Hull © The Estate of Euan Uglow