Ben Nicholson returned to relief carving with gusto shortly before moving to Switzerland in 1958. Throughout his Swiss period, his highly original reliefs won him more critical recognition and international attention than he received at any other time in his career.

Ben Nicholson

November 1960 (Anne), 1960

In December 1933, a chip fell from one of Ben Nicholson’s (1894–1982) prepared gesso grounds. The accident was propitious and encouraged him to explore the literal depth which a picture could sustain. He started systematically excavating circles and rectangles from deep wooden boards and progressed rapidly to a distinctive abstract style. By carving into these wooden surfaces Nicholson increasingly found he could create nuanced effects of texture and relief. Though for a time white washing was integral to the carved reliefs, this was not a permanent feature and he later used both colourful and unpainted finishes.

Writing in 1981, the art historian Charles Harrison estimated that in the 1930s ‘Nicholson’s work and activities [were] central to the promotion of abstract art in England’. He went on to suggest that ‘no other English painter exploited the technical aspects of Braque’s and Picasso’s work to the extent that Nicholson did.’ With time Nicholson’s reliefs have become totemic, being widely regarded as his artistic signature and recognised in histories of the period as an original development from the scratched incisions of the Cubists. The reliefs of the 1930s epitomise nascent modernist aspirations in Britain at the time, with examples being acquired by significant individuals such as Kenneth Clark (who kept it in his bedroom) and John Piper (who kept it on top of his piano).

Though Nicholson temporarily moved away from relief carvings during and after the Second World War, he later returned to the method with gusto. From 1955 until the early 1970s, he made reliefs in a new idiom distinguished by more curvaceous forms, more complex relations of rectilinear planes, and a muted palette suggestive of natural materials. His return to relief carving coincided with his period living in Switzerland between 1958 and 1971. Swiss-manufactured ‘Pavatex’ became a definitive aspect of the new reliefs, as Nicholson wrote to his friend Adrian Stokes.

The new material is a universal building material […] – it’s very hard and unless reinforced is brittle. It is not pleasant to carve like wood [because] it’s a ‘dead’ material but one becomes so keen on one’s idea that the dead material quickly becomes alive. […] I like the hard physical work [because] it’s all towards an end and I can become more and more identified with the material.

The relief November 1960 (Anne) was made using the self-same Pavatex. The distinctively pitted, fibrous surface of Pavatex at lower left contrasts with a freely brushed wash of thinned oil paint, a painterly addition which frames the work’s rectilinear structure and provides an elemental contrast. Despite its title, the work itself gives no hint of personality or individual character. As he explained in a letter of 1968, his titles were not to be regarded as descriptions of any apparent subject-matter. They were rather ‘a luggage tag often deriving from some book […] – or from a radio programme or gramophone record’. Nevertheless, place names are far more common ‘luggage tags’ than the names of people in his work. The title November 1960 (Anne) naturally raises a question about Anne’s identity. Alas, InSight has no definite answers. Though Nicholson’s paternal grandmother was known as Ann or Annie, she died when he was just five years old.

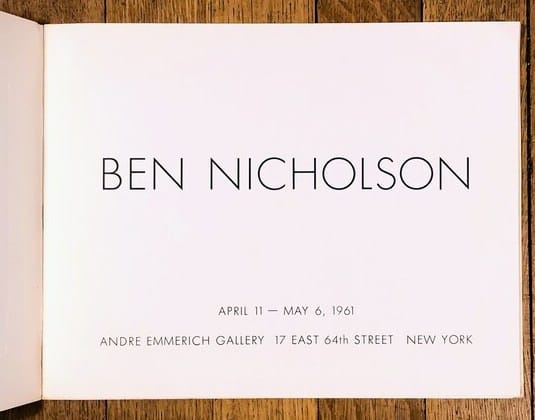

An American audience was kept abreast of Nicholson’s Swiss developments by André Emmerich Gallery in New York. Shortly after completing November 1960 (Anne), a solo exhibition of Nicholson’s work opened there in April 1961. (The gallery sold this particular work to Robert M. Benjamin, a corporate lawyer, and his wife Helena W. Benjamin, who collected contemporary art and took an interest in the Whitney Museum of Art where Helen served as a trustee on the Painting and Sculpture Committee.) Emmerich also showed in 1961 the work of Helen Frankenthaler, Theodoros Stamos and Hassel Smith – company which suggests how readily Nicholson’s work was assimilated into the high noon of American abstract painting. This was the period in which Nicholson’s work received more critical recognition and more international attention than perhaps any other of his career. The continuing quality and free invention of his reliefs were to thank.

Images:

1. Ben Nicholson, November 1960 (Anne), 1960, oil on carved board, 34 ½ x 20 in | For Sale

2. Ben Nicholson, 1935 (white relief Quai d’Auteuil), 1935, The Hepworth Wakefield © Angela Verren Taunt

3. Photograph of Ben Nicholson and Barbara Hepworth in the Mall studio, circa 1932

4. Pavatex factory at Cham, Switzerland

5. November 1960 (Anne) (detail)

6. The catalogue which accompanied Nicholson's 1961 André Emmerich Gallery exhibition