SICKERT: THE THEATRE OF LIFE opens at Piano Nobile this week. InSight focuses on a highlight from the exhibition, a war-time masterpiece from 1914.

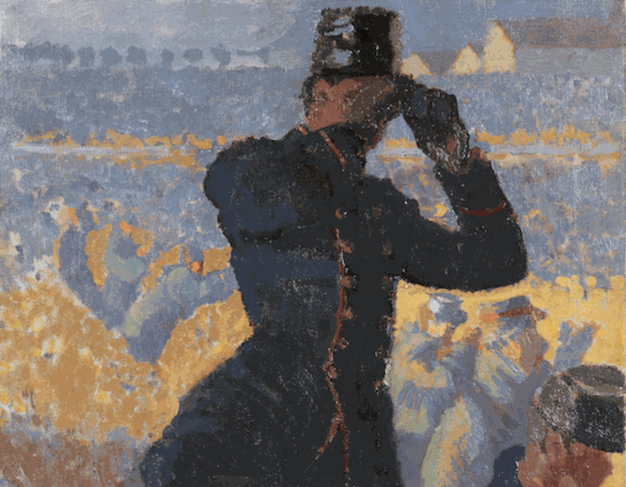

Walter Sickert,

The Integrity of Belgium, 1914

When the Great War arrived in September 1914, Walter Sickert (1860–1942) greeted it with a mixture of tense apprehension and jingoistic enthusiasm. He paid close attention to unfolding events at the outset. In November 1914, a moment of considerable uncertainty in the conflict, he reported a stream of war-related gossip in a letter to his friend Ethel Sands: Poincaré was rumoured to be planning a peace treaty with the Germans if Paris fell; the wife of a Belgian officer had expressed reservations about establishing voluntary hospitals there; contrary to some rumours, Rheims Cathedral was still standing (though heavily damaged). The letter also referred to Sickert’s pupil-to-be, Winston Churchill, who was First Lord of the Admiralty at the time. ‘Winston was at Antwerp. My Belgian friend saw him there. Our expedition is regarded as a bad gaffe.’

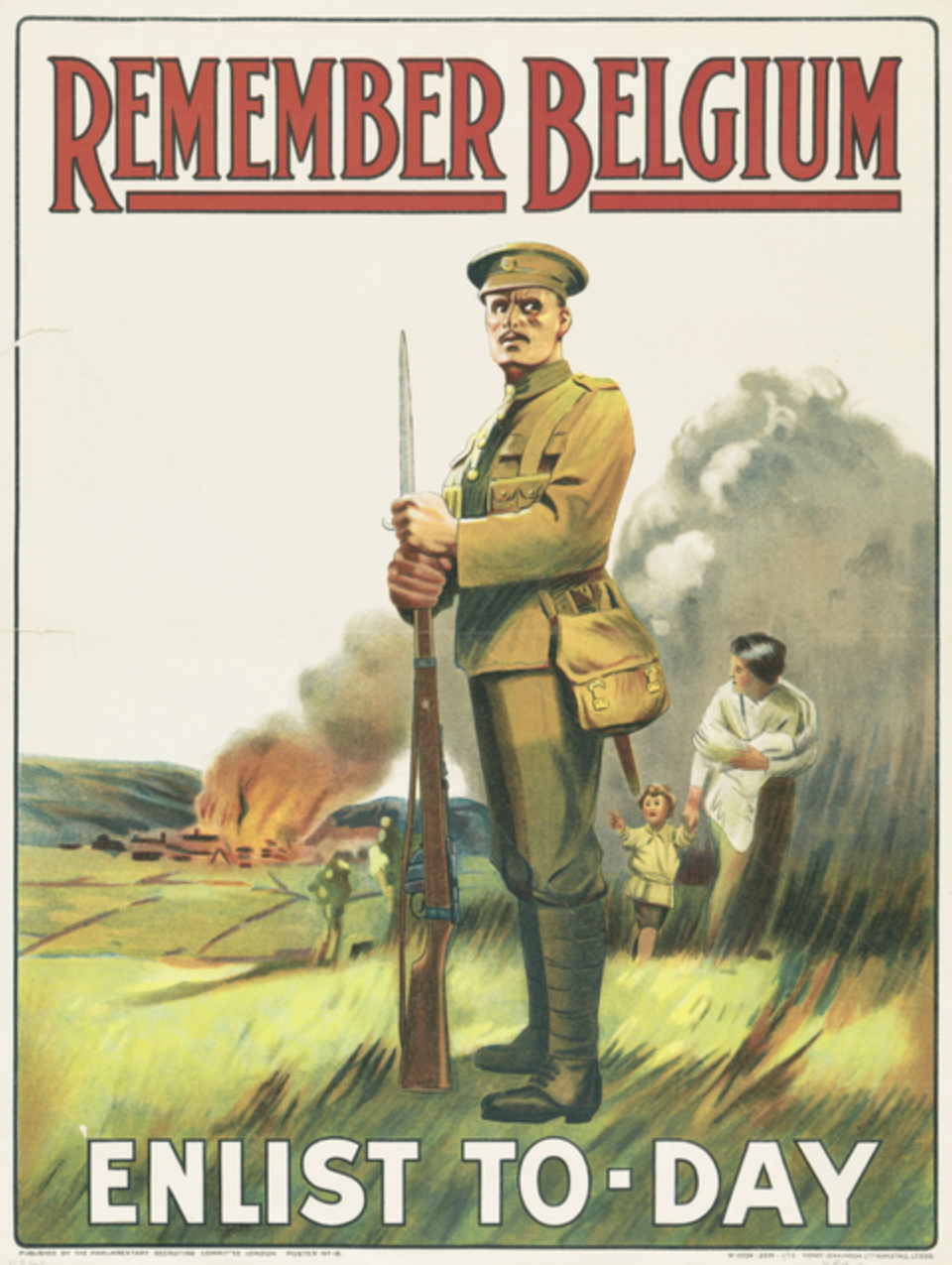

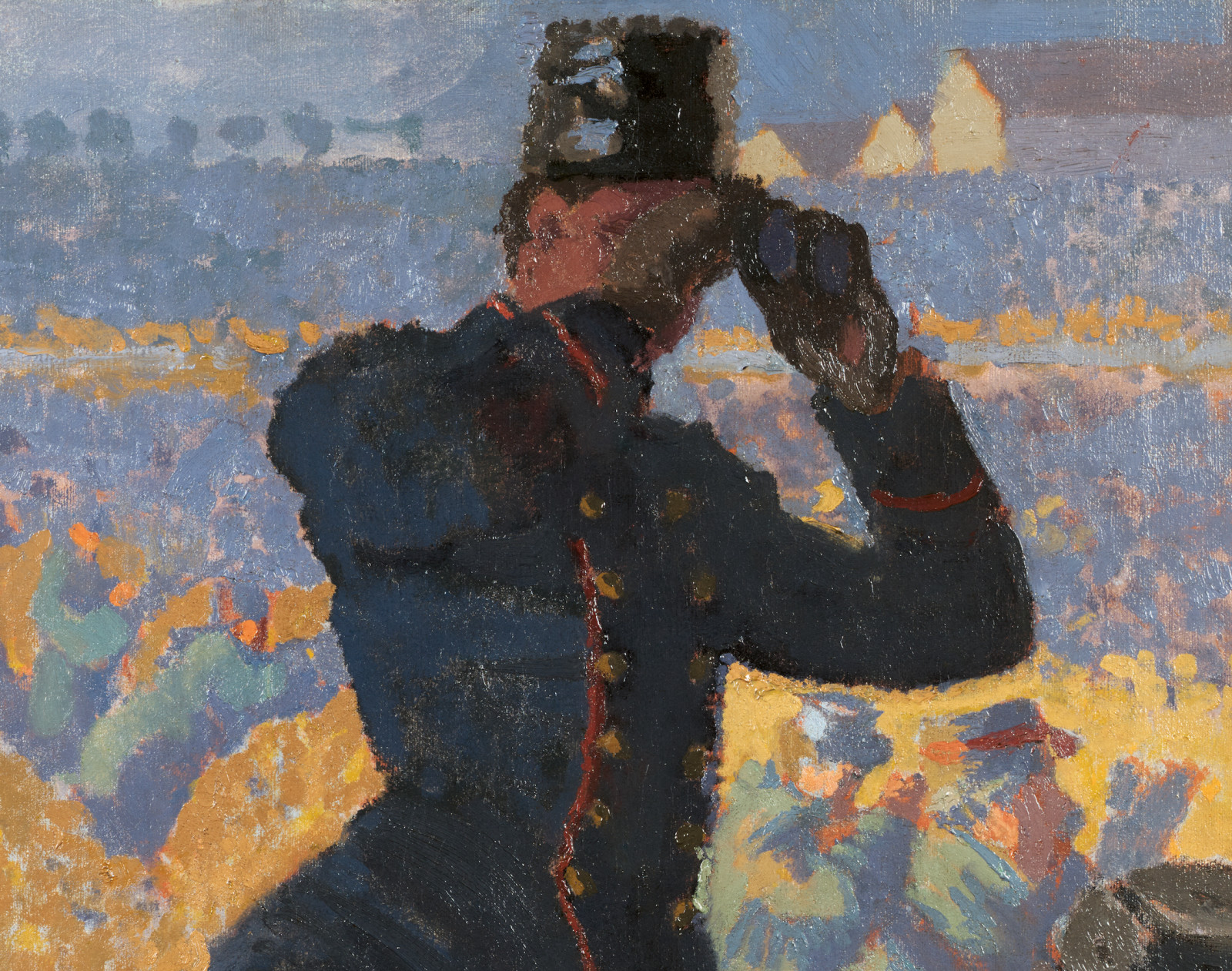

During this period of heightened excitement and activity, before the horrific implications of mechanised warfare became apparent, Sickert made two overtly propagandist paintings. The Integrity of Belgium depicts a Belgian officer half-kneeling in the foreground, ‘leading the attack’ as The Sunday Times critic wrote in 1915. Six other Belgian soldiers fill a trench which stretches away into a glistening, mist-shrouded landscape. While it bears a passing resemblance to the compositions of contemporary propaganda posters, The Integrity of Belgium addresses the plucky valour of Belgium’s army rather than emphasising the innate villainy of German soldiers. (Elsewhere, Sickert expressed unease at the frankly xenophobic profiling of German nationals then taking place in England.) Even as the work communicates a stirring message of war-time heroism, the veiled eyes of the central figure – concealed behind flashing binoculars – provides a Sickertian touch of studied ambiguity.

The other of Sickert’s propaganda pieces was Soldiers of King Albert the Ready. The painting depicts Belgian riflemen, studied (as Robert Emmons recounted) from ‘Belgian soldiers, whom he had met at cafés and invited round to the studio’. ‘For a while [Sickert’s studio] was tripping-full of ripples, boots and other military accoutrements.’ According to Sickert, ‘The artilleryman’s forage cap with a little gold tassel is the sauciest thing in the world.’ The picture measures nearly seven feet in height – an extraordinary size for Sickert, who self-consciously followed the dictates of the market and typically made paintings to suit the scale of modern domestic spaces.

Both Soldiers of King Albert the Ready and The Integrity of Belgium were executed using Sickert’s tonal ‘camaïeu’ method (see InSight LII). Because of its great size, however, Soldiers of King Albert the Ready failed to achieve the richly painted, imaginatively executed surface found in The Integrity of Belgium. In this work, the contrasts of unmodulated lilac, green and orange are redolent of the ‘Post-Impressionist’ art exhibited a few years earlier at the Grafton Galleries, as are the broken dabs and strokes of impasto which make the work crackle and hum. Despite publicly criticising the exhibitions at the time, Sickert was evidently affected by a change in the artistic climate which the Grafton exhibitions brought about.

The Integrity of Belgium was painted at a moment of transition in Sickert’s career. The year 1914 not only saw him adopt a much lighter palette; he had after all been observing ‘colour in the shadows’ under the influence of Pissarro and Spencer Gore for some years. The war disrupted his long habit of summering in France, his pleasant scenes of Dieppe all but ceased, his Camden Town period of quiet domestic tragedy came to a close, and a streak of vibrancy emerged in his work with new subjects and greater painterly freedom than before. Sickert’s late masterpieces of the 1920s and ‘30s – works like Victor Lecour, The Tichborne Claimant and La Louve – stand on the shoulders of great paintings made in this transitional period. Foremost among them is The Integrity of Belgium, the artistic vitality and striking imagery of which is still impactful over a century after its making.

Images:

1. Walter Sickert, The Integrity of Belgium, 1914, UK Government Art Collection

2. ‘Remember Belgium’ propaganda poster, 1914

3. The Integrity of Belgium (detail)

4. Walter Sickert, Soldiers of King Albert the Ready, 1914, Museums Sheffield

5. An installation shot from SICKERT: The Theatre of Life

6. Walter Sickert, The Tichborne Claimant, 1931, Southampton City Art Gallery

(Also on view in SICKERT: The Theatre of Life)