A pioneering abstract painter of the post-war years, Albert Irvin OBE RA made some of his most ambitious and inspiring works in the 1980s and ‘90s.

Albert Irvin OBE RA

Lexington II, 1989

From the late 1950s until his death, Albert Irvin (1922–2015) was an abstract painter. As for many artists of his generation, his early career and training were interrupted by the Second World War. Nevertheless, by the early 1960s he had achieved a degree of distinction, making turbulent transatlantic canvases which related as much to Roger Hilton as to Willem de Kooning. A work of this period called Evening was purchased by the Arts Council in 1961 and, more recently, the Tate Collection acquired another painting with fraught energy from the early 1960s, Enclosed, which was in Irvin’s personal collection until his death.

Image: Albert Irvin, Enclosed, 1963, Tate Collection © The Estate of Albert Irvin

In the mid-1960s, Irvin’s work changed. Between 1964 and 1966, his palette lightened dramatically as he began to use pure, unmixed colour. The definitive hues of his palette were green, orange, and red, and his personally distinctive use of these colours continued for the rest of his career. In retrospect, this vibrancy and clarity of colour is comparable to the painterly abstraction of his contemporaries such as Gillian Ayres and Howard Hodgkin.

Image: Howard Hodgkin, Dinner in Palazzo Albrizzi, 1984-88, Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth © The Estate of Howard Hodgkin

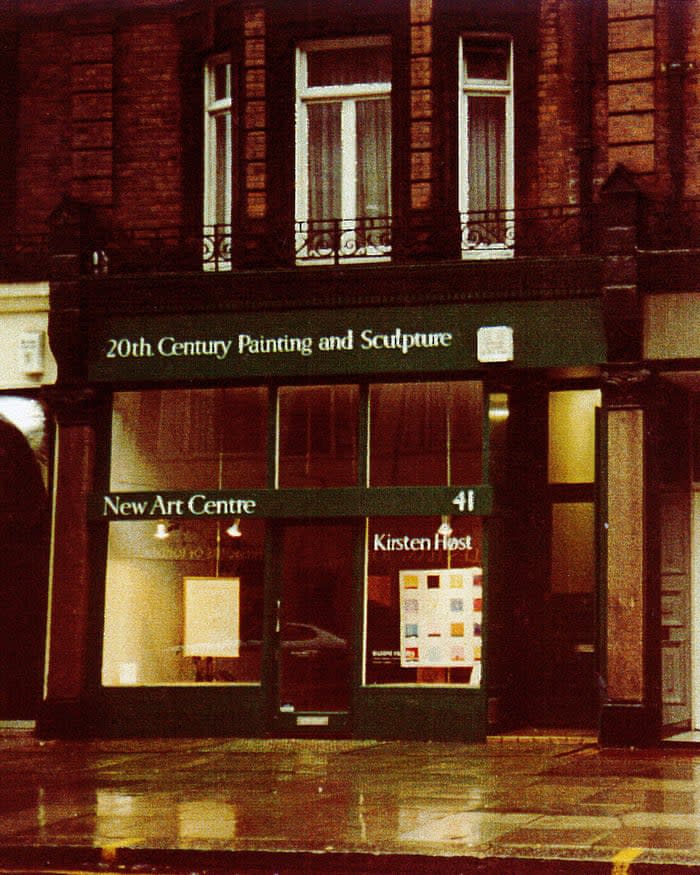

Irvin was one of the pioneering abstract artists exhibited by the New Art Centre at 41 Sloane Street. The gallery was founded as a not-for-profit organisation by Caryl Hubbard and Madeleine Bessborough in 1958. It tended to show abstract work at first – Irvin had five exhibitions there between 1963 and 1975, and its other artists included Sandra Blow and Ian Stephenson. There was no overt programme, however, and the work of talented figural painters like Mary Potter, Jeffery Camp and Prunella Clough was also exhibited.

Image: The New Art Centre, 41 Sloane Street

Though he had used water-soluble acrylic paint since the early 1970s, Irvin enjoyed a resurgence of creativity with this medium in the 1980s and ‘90s. At that time, he explained, ‘I wanted something more direct. I wanted [my work] to have an immediacy of contact with the spectator like music does.’ In a new and visually arresting composition, devised around this time, he began coating large canvases in a uniform ground colour. This underlayer was often in red or blue and, owing to the medium’s translucency, it resounded through the upper layers of paint, causing the entire painting to glow with striking intensity.

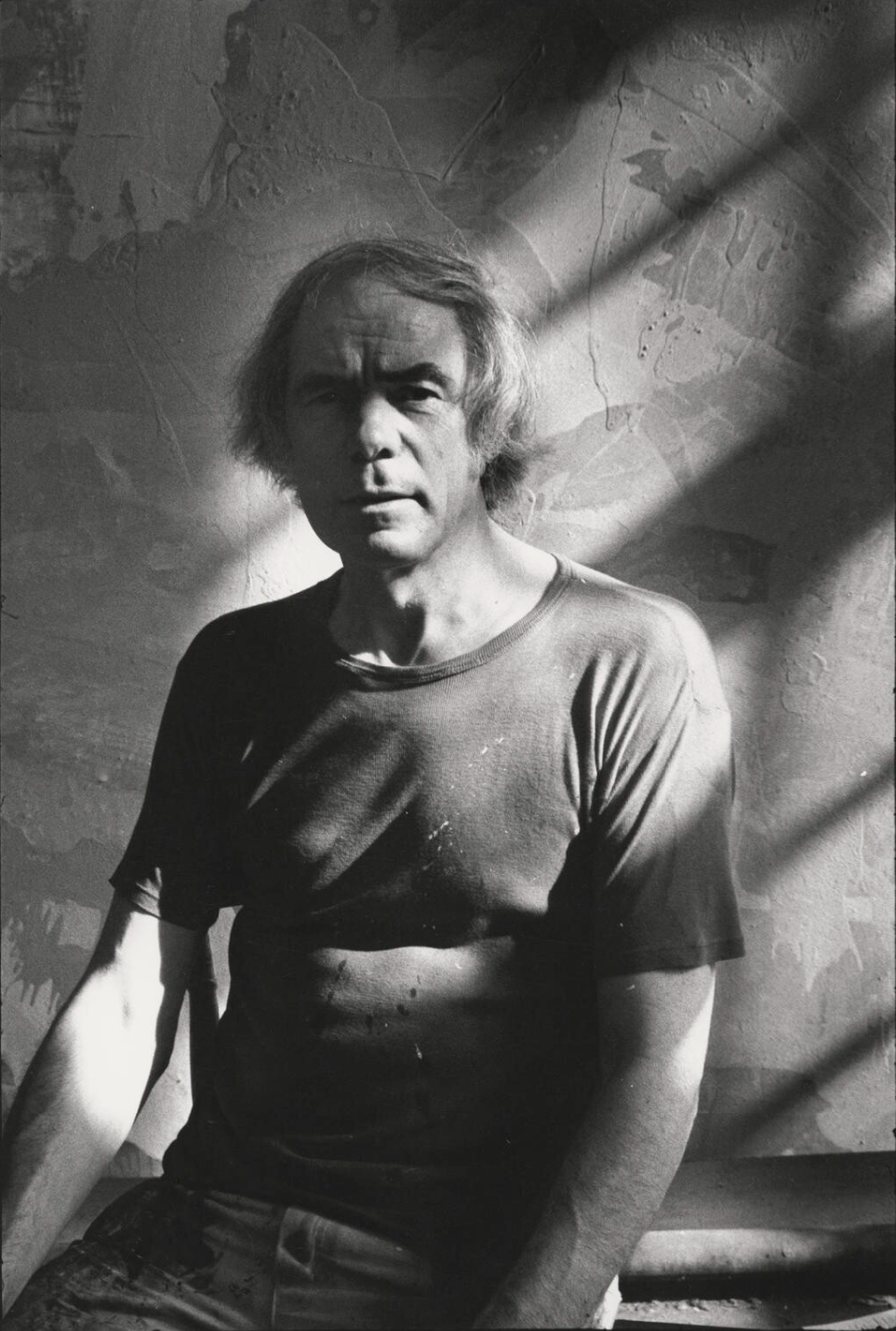

Image: Albert Irvin, 1980, photographed by Harry Diamond © Harry Diamond

At the same time as applying a uniform underlayer, Irvin devised a distinctive language of brushstrokes. Vast, singular applications of paint – what he called ‘autographic marks’ – were built up in elementary patterns of parallel lines and cross hatching, often using a simple # layout. These patterns were often layered one on top of another, creating a lively visual cacophony. Large scale, effervescent works such as Lexington II and St Germain have an all-over composition and were executed in an improvisatory mode. The trance-like richness of their contrasting colours – pink beside orange, purple beside red – delivers a straightforwardly sensational response in the viewer: immediate, satisfying, and unfailing.

Albert Irvin, St Germain, 1995, Tate Collection © The Estate of Albert Irvin