Though Frank Auerbach received his formal training at St Martin's School of Art, the evening classes of David Bomberg which he attended were of much greater importance to his artistic development.

Frank Auerbach

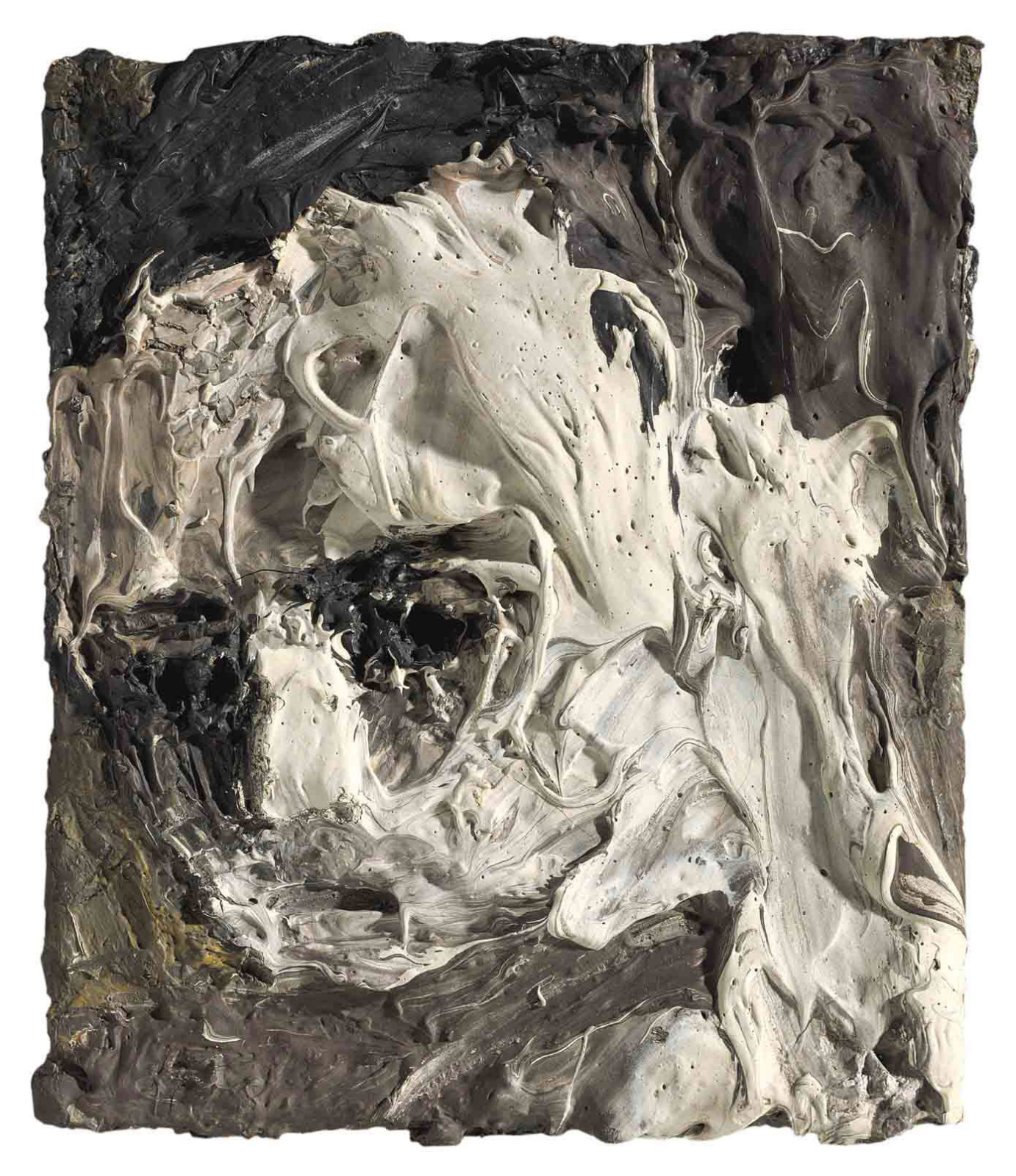

Reclining Nude, 1954

Auerbach (b. 1931) has spoken several times about Bomberg’s classes, which he attended at the Borough Polytechnic between 1948 and 1953. In 1978, he said to Catherine Lampert that Bomberg himself was ‘probably the most original, stubborn, radical intelligence that was to be found in art schools’. Speaking to the art critic Robert Hughes a little later, he said,

What happened was that people would draw. As soon as they seemed to be drawing in a way that was bitty, affected, mannered or using a cliché learned from art, he would refer them to the model and… suggest a total destruction, and they would destroy it and go on; […] I absolutely needed the feeling of breaking through into uncharted territory, and working in a world where no rules were known and anything was possible. I had caught a glimpse of that in Bomberg’s classes: a larger improvisation of gestures that might pull forms out of thin air.

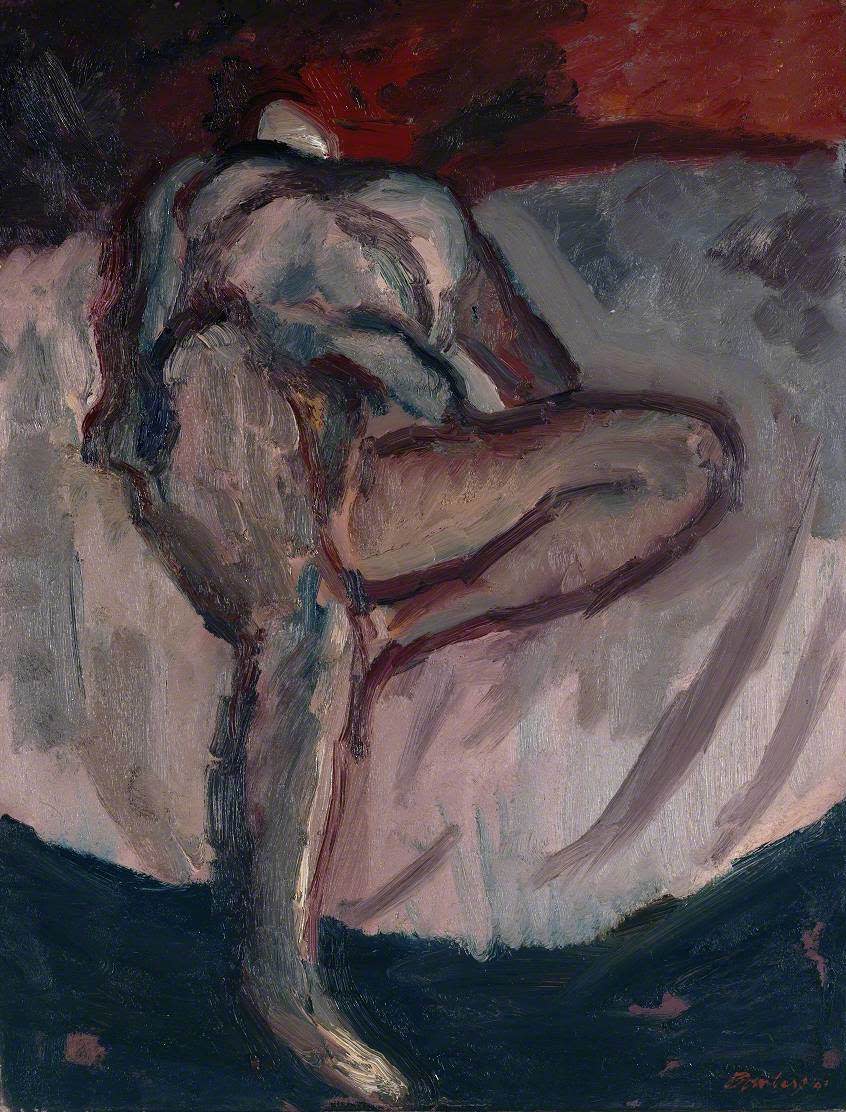

Though Bomberg is better known for his other work, especially landscapes, his images of the female nude are striking, intimate and often brooding. A life study in oils from 1943 has some of the immediacy and informality more usually associated with the next generation of figure painters, including Auerbach and his friends Lucian Freud and another attendee of the Borough evening classes, Leon Kossoff. The reclining figure – its torso steeply foreshortened, its chin viewed in profile from below – has some of the qualities apparent in a work like Auerbach’s charcoal drawing Reclining Nude.

Auerbach has long acknowledged the effect that Bomberg’s ‘practical instruction’ had on his development. He made Reclining Nude in the life room of the Royal College of Art, just a year after he ceased to attend the Borough classes, and it shows the scabrous charcoal medium and inventive mark-making encouraged by his former teacher. This is evidently a work of Auerbach’s, however, and not Bomberg’s. The heavily emphasised contours are worked into the paper repeatedly. Even as they outline the figure and suggest its weight and presence, they act like lines of force, creating new and unfamiliar contours within the human body. (‘[T]he marks that seem to stand for something nameable and those marks which seem to you to be inventive ones, are not in my mind separate.’) The layered construction of the drawing also differs from anything of Bomberg’s. Beneath the body, a skin of scribbles and hatching evokes the structure against which it reclines. These marks grin through the figure, enriching its vital, flickering substance.

Early on in Auerbach’s career, colour was mostly limited to a narrow range of paints. Brown, black, ochre and white were ubiquitous. The art critic Martin Gayford has explained that, as a poor art student, ‘Auerbach could only afford sombre earth colours – so ochres and browns predominated’. His use of charcoal, first taken up under Bomberg’s tutelage and continuing through much of his career, indirectly relates to his monochrome paintings and most especially those executed exclusively in black and white oils. In each case, the heavily worked appearance of such singular materials – charcoal and monochrome paint – delivers an art which is undressed and unadorned, revealing the scaffolding of its construction.

This quality of something unadorned is closely connected to Auerbach’s depiction of naked bodies that are care-worn, unconceited, vital. His intention was not only to avoid ‘the ideal’ in art, but for the artist to behave as if they had no awareness of it. As he said in 1959, a few years after Reclining Nude was made, ‘one has to be to be true to [the object], then one’s more likely to get a unique result.’ Nearly seventy years after it was made a charcoal like Reclining Nude still jolts the viewer, proving the forceful technique and assiduous observation of its maker.

Images:

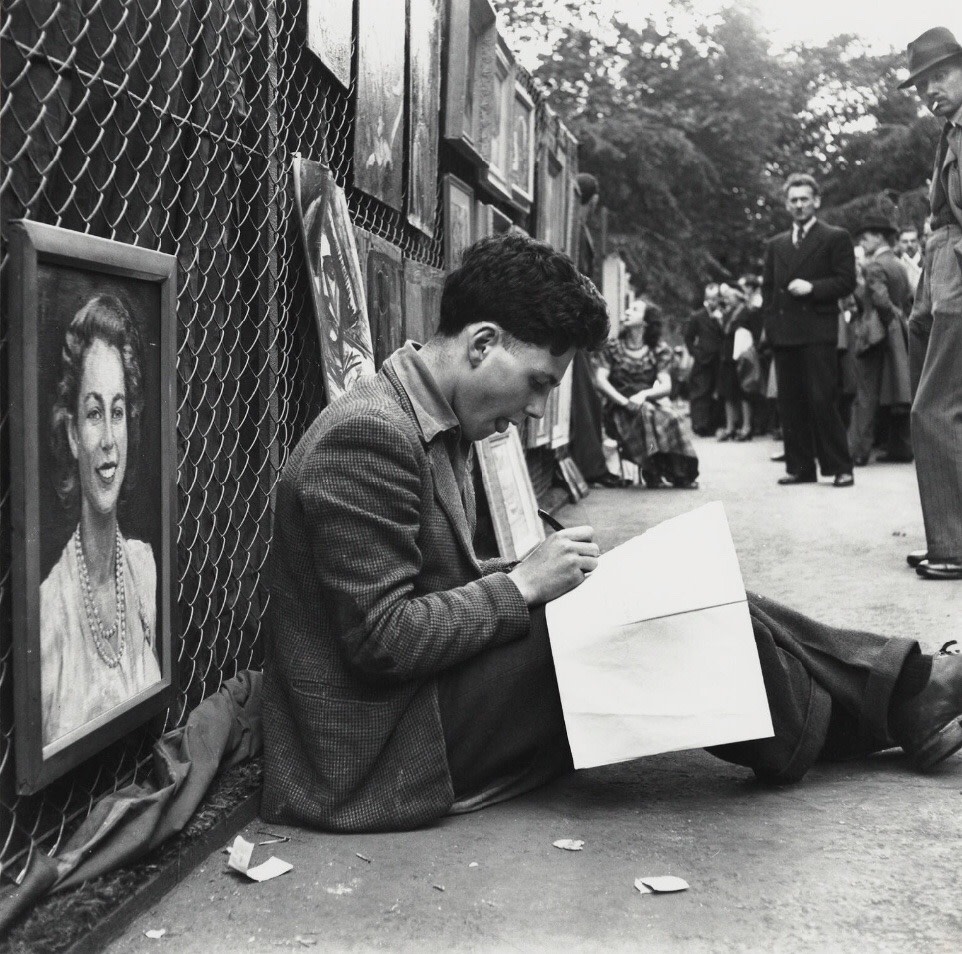

1. Frank Auerbach, 1948, photographed by Daniel Farson © The Estate of Daniel Farson

2. David Bomberg, Nude, 1943, Tate Collection

3. Reclining Nude (detail)

4. Frank Auerbach, Portrait of Leon Kossoff, 1953, Private Collection © Frank Auerbach