In the late 1940s and the early 1950s, Graham Sutherland experienced a burst of artistic invention and critical recognition.

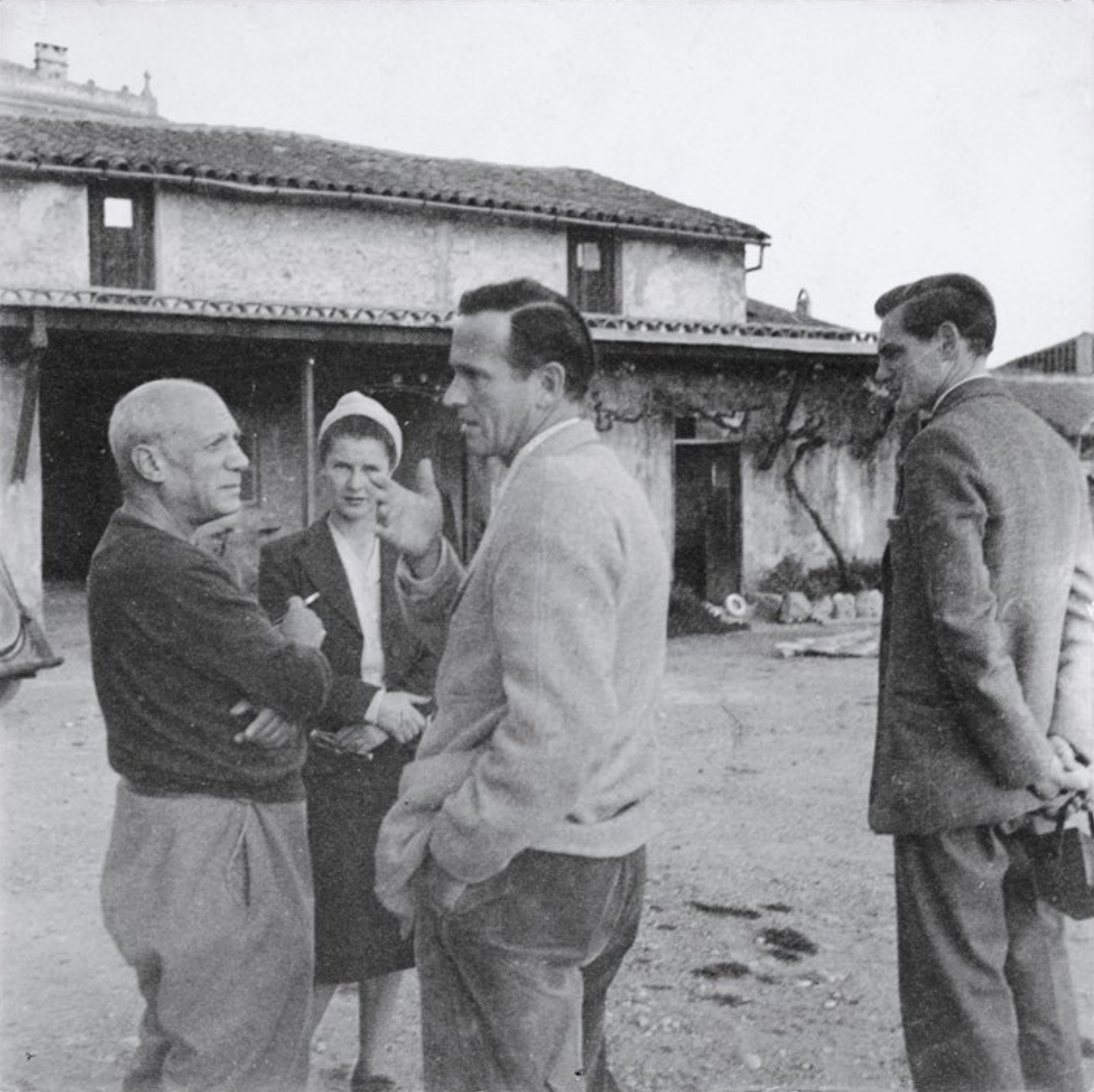

In 1947, Graham Sutherland (1903-1980) paid a seminal visit to the south of France. Though it was prompted by his wife Kathleen's poor health, the trip was revelatory: the climate, colours and artistic connections all had a decisive effect upon Sutherland's art. He met Picasso and Matisse for the first time, personal connections which raised his awareness of their art, and he subsequently commented that 'one would have to be blind not to profit by the new role of colour invented by Matisse'. Every year thereafter, Sutherland spent part of the year in France. As John Richardson later commented, by the mid-1950s he was 'on the friendliest terms with most of the top froth of the Riviera'.

This period marked not only Sutherland's social, but also his artistic, ascendancy. Following his first portrait in 1949, which depicted Somerset Maugham, a new clientele emerged. More than this, his powers of invention surged - acid tones of pink, orange, blue and green complemented a new cast of forms and presences, vines and palms. The end of the 1940s and the beginning of the 1950s was a time of mid-career vitality, the height of Sutherland's celebrity and creativity. The accolades grew in number and significance, from his prize-winning contributions to the Venice Biennale in 1952 to a commission for the east wall tapestry of Coventry Cathedral, a work which is still reputed to be the largest tapestry ever made.

A seminal series of work from this time, 'Standing Forms', cont

ributed to the excitement and energy around Sutherland and his art. One of the earliest paintings from this group, Standing Form Against a Hedge, was immediately acquired by the Arts Council Collection when it was shown at the Hanover Gallery (see InSight 18) in 1951. These paintings created abstract, sculpture-like figures, sometimes raised on a pedestal and given a clear spatial relationship to a colourful, decorative background. Consistent lighting and resulting effects of surface modelling are implied by arrangements of colour and shape, and in one work from the series, Armoured Form, the central figure throws a looming shadow against the back of the tightly defined setting.

The success of the Standing Form paintings is underpinned by their subtle morphology. Each figure suggests a wide range of associations and permits many possible readings. Despite its title, Armoured Form has an arresting mixture of anthropomorphic and insect-like qualities. Several closed eye lids, such as they appear, presumably derive from the epaulets of a suit of armour. The extended, orb-like head performs a similar visual pun, flickering between a metallic visor and a sharp-toothed monstrosity; some aspects of the form resound with echoes of violence and conflict. No reading is definitive, however, and other writers have discerned more sensual, sexualised connotations in the Standing Forms.

The themes of Sutherland's series, ranging from violence to sexuality via organic humanoid forms, were also of interest to the other eminent British artist of the time - his one-time friend Francis Bacon. It was in fact Sutherland who introduced the great painter to Lucian Freud, as Freud later recalled. I said, tactlessly, "Who do you think's the best painter in England?" He said, "Oh, someone you've never heard of: he's like a cross between Vuillard and Picasso; he's never shown and he has the most extraordinary life: we sometimes go to dinner parties there." In 1944 or '45, Sutherland had come across Bacon as 'a quiet roulette-playing gent who lives in South Ken'. Though the friendship later soured, a victim of Bacon's merciless tongue, the connection is telling; Sutherland's place is at the highest level of British painting in the twentieth century and works like Armoured Form go some way towards explaining why.