Grinding his own pigments and working from his own image, Tony Bevan is a self-sustaining artist of inventive means and personally distinctive imagery.

Over the last few centuries, many visionary artists have enhanced their paintings with an injection of texture. They often used materials other than paint to do it. Joshua Reynolds used wax to achieve a skin-like shine on the picture surface; Turner used mastic gum in his late sunsets; Braque and Picasso reorganised their paintings around added collage and papier collé; Sickert sometimes left his canvases in the rain, relishing the resultant stains and pockmarks; and Michael Andrews famously infused his paint surfaces with sand from Uluru and mud from the riverbank of the Thames. In each case, the desire was to create new and richer visual effects. One artist still living with this desire is Tony Bevan (b. 1951).

Bevan studied at Goldsmiths’ College and the Slade School of Fine Art in the mid-1970s. In the 1980s, he quickly became a central contributor among a generation of figurative painters which included Lisa Milroy, Ansel Krut and Stephen Farthing. The challenge for these artists was not to undermine the image-in-paint breakthrough made by Bacon, Freud, Kossoff and Auerbach, but to reconnoitre territory beyond it. Despite the prominent material qualities in their work, Bevan and his contemporaries also sought out new imagery and were more open to overt iconographic references, in this respect developing hints found in the art of Michael Andrews and R.B. Kitaj.

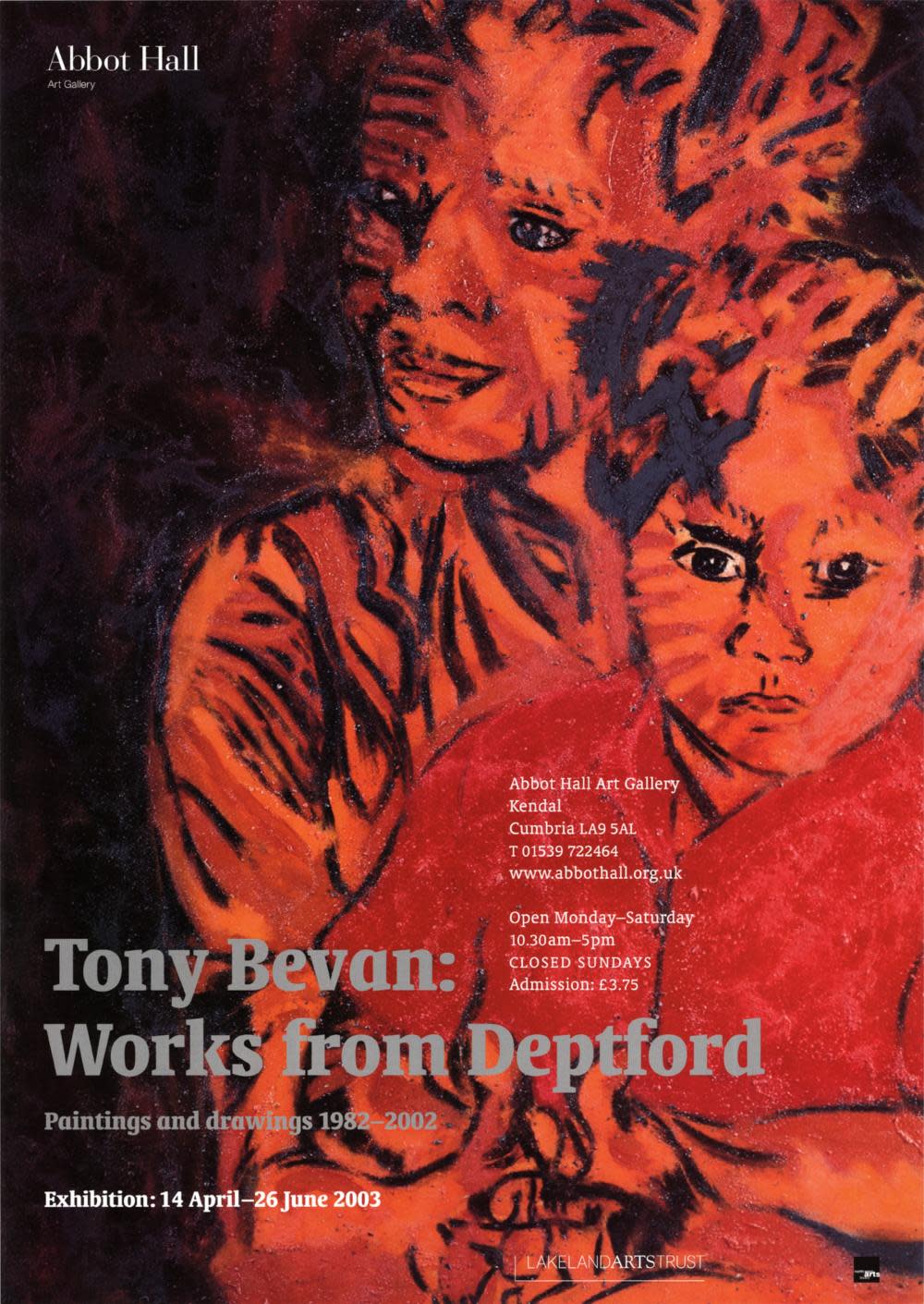

Not since the nineteenth century have advanced artists been allowed to assume the basic components of painting; it is no longer as simple as brush, paint, primer and canvas. This is not least because painting’s detractors have claimed to possess more interesting artistic means, with painters responding in turn by discovering new idiosyncrasies in the basic components of their craft. Bevan’s work is notable for certain bespoke technical innovations. Preparing his canvases with a clear and glossy sizing medium, he emphasises the texture of the underlying support, and by grinding his own pigment and suspending it in an acrylic medium, he gives the paint itself a rich granularity. Writing of Bevan’s Abbot Hall exhibition in 2003, The Guardian critic Alfred Hickling referred to the artist’s ‘vast, floury canvases caked in hand-ground pigment.’

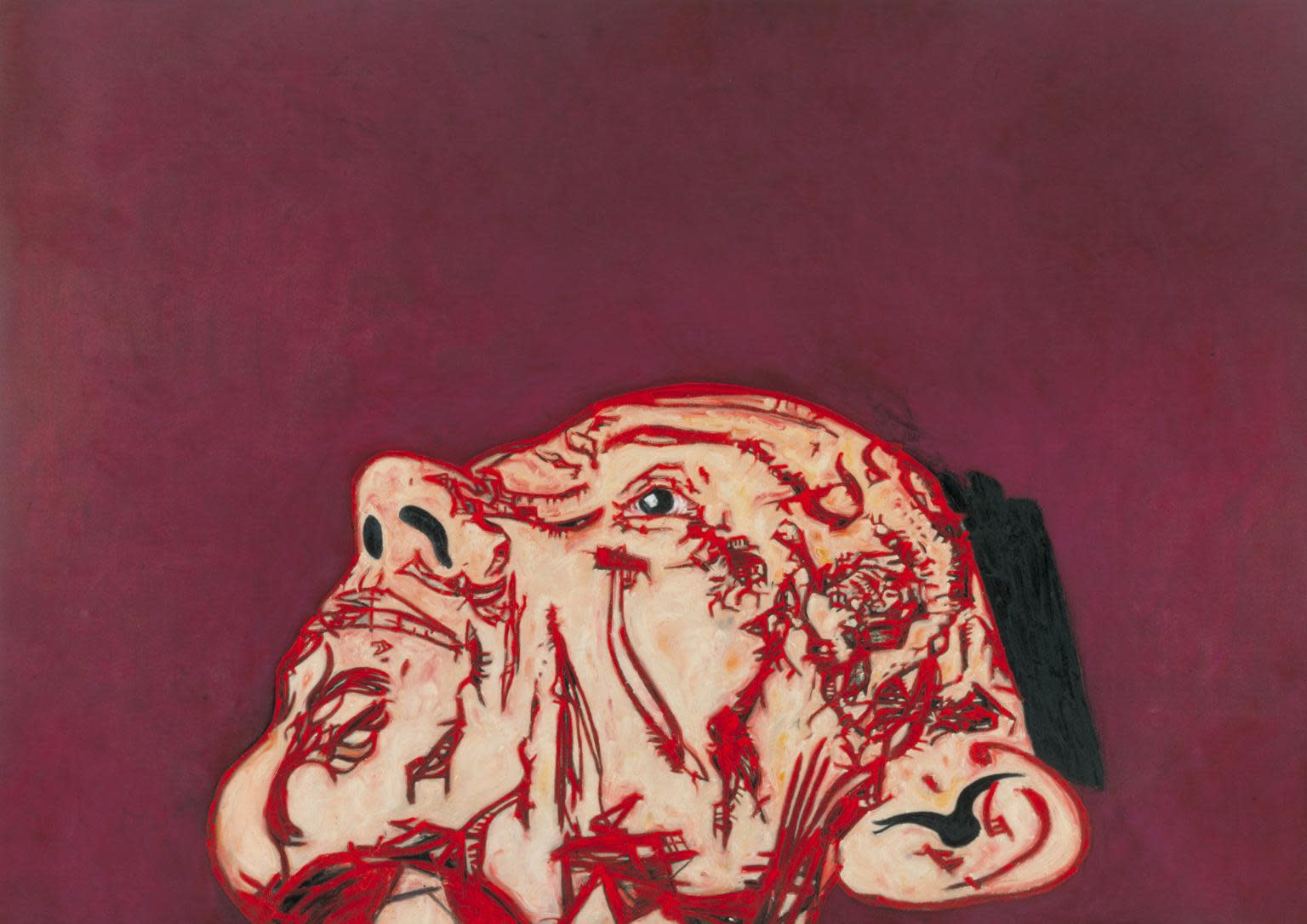

In an interview in 1993, Bevan spoke about using his own body as a subject for his figure paintings.

I don’t find my subjects divorced from me. On the contrary, in many of the works I use myself as the subject. But when I’m working on a self-portrait, I’m not constantly looking in a mirror and correcting. I still work from drawings and there is an evolution through the work itself. It’s not a matter of going back and correcting and formulating some kind of a replica of a person. There is a lot of stripping away. There isn’t a lot of excess baggage.

The hands in Locked Fingers are most likely the artist’s own. (An intriguing difficulty is posed here about how an artist performs a life study when the relevant limbs are also those required to make a mark.)

Locked Fingers was made in Bevan’s studio in Deptford, South-East London. The artist’s distinctive process, used in this work and others from the 1980s and ‘90s, was recently described in a Tate Collection catalogue entry.

He began work […] by making preliminary studies in charcoal, after which he drew the image in charcoal onto the canvas while it was still wet with the sizing medium so that the dark lines would be absorbed into the canvas’s fibres. The painting was positioned flat on the floor of his studio in order to be painted, with the artist working on his hands and knees, and it was only placed loosely onto a stretcher once complete.

This highly original process is just one half of Bevan’s achievement. Without his work’s striking imagery – the strained sinews of hands and neck, for instance – the process in itself would be of little value. As it is, works like Locked Fingers belong to a history of textured painting, their place secured by both an inventive process and vivid subject-matter.