After settling in Cape Town in 1920, Irma Stern started making regular painting trips to tribes around the Cape. Working at the height of colonial rule, an untroubled formalist approach yielded striking artistic results.

According to South African History Online, the Xhosa people are the second largest cultural group in South Africa after the Zulu-speaking peoples. At one time a settled agricultural society, between the late eighteenth and late nineteenth centuries the Xhosa suffered repeated attempts by European settlers to displace and dispossess them from their home in the Eastern Cape. When Irma Stern (1894–1966) drew this Xhosa woman in 1935, there was a state of relative peace between the settled European populations and long-resident ethnic peoples. Though Stern herself was born in the Transvaal, her parents were German settlers and she herself paid regular visits to Europe. Her attitude to subjects like this African woman – the figure fluently outlined, the skin tones subtly modelled – was that of a fascinated outsider peering in.

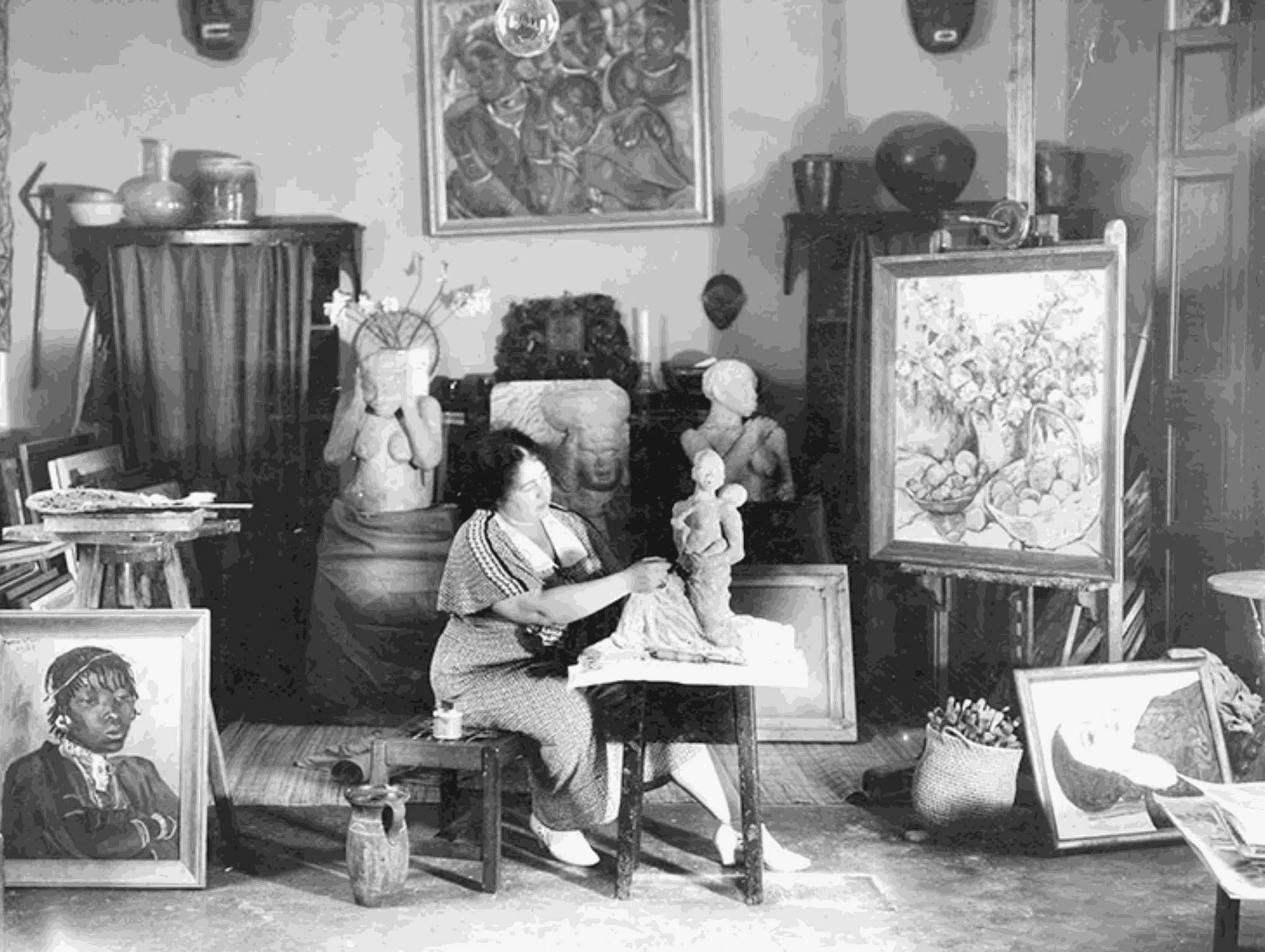

From 1939, Stern began travelling further into the wilds of southern Africa. Though she had started making regular painting trips around the Cape after settling in Cape Town in 1920, it was not until the late 1930s and ‘40s that she visited Congo and Zanzibar. She published a number of small books after these trips, presenting herself as an intrepid explorer in search of the ‘natives’. One of these, published in 1943, focused on her travels to Congo.

In a clearing of the jungle a circle of native huts is seen, all gaily decorated with a variation of geometrical ornaments, painted in fresco. I went out to meet the Sultan and asked his permission to stay. This chief is abundantly full of life; he does everything with an absolutely devastating overflow of vitality.

The relationship between white artists of European heritage and their African subjects was implicitly colonialist, and only in recent decades has this fraught subject been addressed critically. A retrograde attitude was still evident at the Museum of Modern Art’s famously controversial 1984 exhibition, “Primitivism” in 20th Century Art: Affinity of the Tribal and the Modern. Its failings were spelled out in the journal October by the critic Hal Foster, who criticised the curators for adopting the same unsympathetic approach to African tribal society as the early twentieth-century artists whose work was on display. Rather than treat African cultures as just that, the exhibition treated masks and tribal ‘art’ as a formalist sourcebook for western painting.

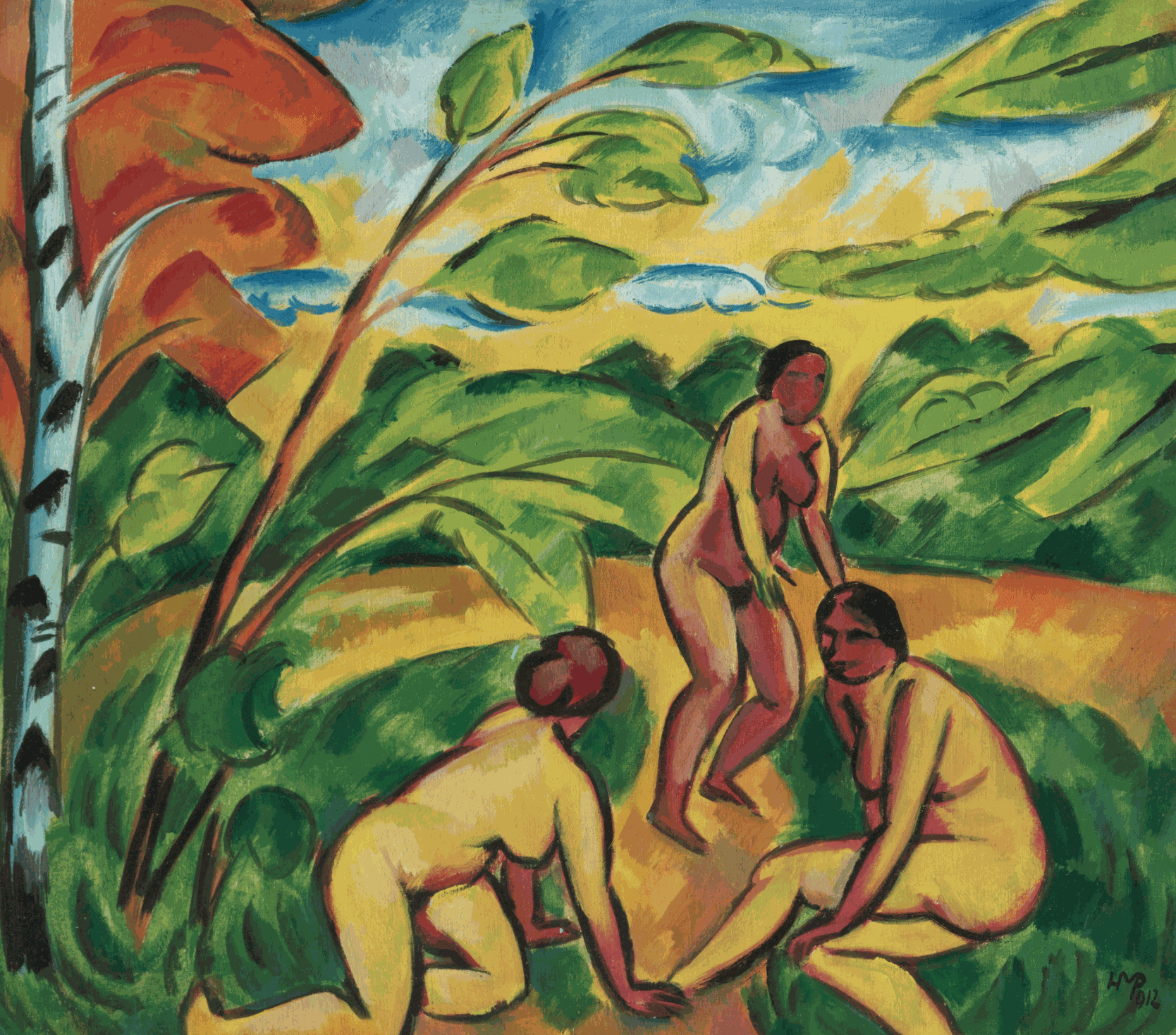

At the height of colonial rule, an untroubled formalist attitude yielded striking artistic results. Following from Picasso’s celebrated (if problematic) use of tribal masks in Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, completed in 1907, German Expressionist artists also began to experiment with African sources and figure types. One such artist was the academically-trained Secessionist Max Pechstein, who met Stern in 1917 and encouraged her studies. Stern’s later investigations of the African interior mirror the odyssey which Pechstein and his wife undertook in 1914, when they travelled to Palau, Polynesia, in search of adventure and subject-matter. Pechstein’s orientalist fantasias were a formative example for Stern.

In recent years, some of Stern’s supporters have preferred to praise her talents without addressing her problematic assumptions. Yet her life undeniably followed the paths of exchange and practices of appropriation created by colonialism; no complete discussion of her work today can avoid this. A recent monograph about Stern wrestles with how to reconcile an appreciation of her work while acknowledging its colonial implications. The book was published last month and its author, Sean O’Toole, touched on the conundrum in an article for Apollo magazine.

Dispossession is a recurring and unsolved dilemma of African life. Stern's realism, an important hallmark of her middle period, did not engage with this fact; her realism was purely formal, not social. [...] The decorous formalism that has long been the focus of writing on Stern threatens to render her art a relic. Yet her life and work, mired as they are in complication, speak loudly to our contemporary moment.

Where a lesser artist’s work might simply be forgotten, the controversy proving too great a distraction, an artist of Stern’s merit forces the issue. In work of such brilliance, the challenge demands to be addressed.