In 1965, Ben Nicholson discovered a remarkable field of ancient standing stones in Brittany. For the next six years, he evoked the stones in his work using round-edged squares and rectangles.

From the time of his first sustained abstract period in the 1930s, Nicholson (1894–1982) made use of irregular shapes. Though his squares and circles are archetypes of purist Modernism, the geometry of his work is often non-Euclidean. A gentle curve often creates a subtle irregularity which the artist’s friend David Lewis once ambiguously referred to as ‘near-geometries’ (as opposed to ‘precise’ geometries). In a well-known work from the Tate Collection, 1935 (white relief), the central panel is not a rigid rectangle with two sets of parallel lines. Rather, the sides of the panel taper very gently from top to bottom – a natural curvature that suggests the artist’s dominant hand and the direction in which the line was carved.

The use of curved forms was not an incidental quality in Nicholson’s work. As well as giving forms in themselves an appearance of character and liveliness, round-edged shapes helped to evoke naturally occurring or time-worn, human-made edifices. After his first visit to the Stone Age megaliths at Carnac, Brittany, in 1965, Nicholson began to experiment much more extensively with round-edged squares and rectangles. The taper grew more pronounced, sometimes appearing on all four sides of a shape, and the resulting impression is of a presence worn by time and shaped by natural forces.

In a statement published in 1968, Nicholson explained his attraction to the stones at Carnac.

I feel very much at home with the huge standing stones at Carnac in Brittany and the quoits of West Penwith in Cornwall in which the sea also plays a big part. There is perhaps an especial feeling of life because these are not considered ‘works of art’.

This ‘feeling of life’ was precisely the quality he sought to achieve in his work generally and in a series of carved reliefs exploring round-edged forms particularly. Having resumed his practice of carved relief after moving to Switzerland in 1958, Nicholson used the medium for a group of Carnac-related works. The titles of these works vary between formal language (‘squares’, ‘curved form’, etc.) and explicit references to the Carnac stones.

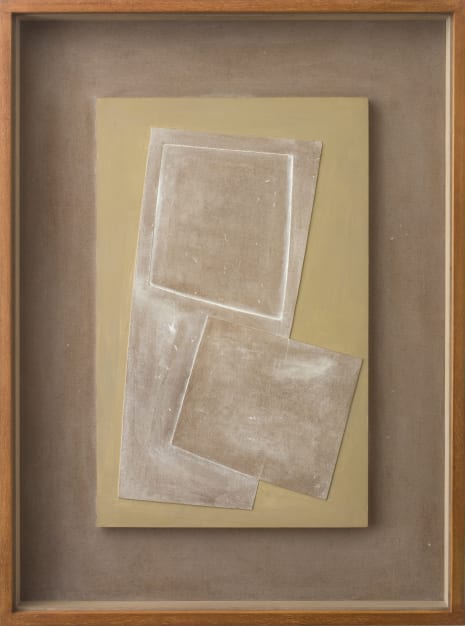

In all of the carved reliefs made between 1965 and 1971, curved forms frequently carry an association with Carnac. Works from this period were exhibited at Marlborough Fine Arts in 1971 and included amongst them was 1971 (two squares and very green). While the two eponymous squares in this work carry no obvious association, the underlying columnar rectangle is redolent of contemporaneous works which make titular reference to columns or standing stones. (A closely related work, 1971 (Carnac with green), uses the same composition of two squares over a rectangle.) As Norbert Lynton wrote in the accompanying catalogue, these reliefs ‘look sharper, tougher and more physically imposing’ than earlier work from Nicholson’s career. A photograph of 1964 shows the artist in his Swiss studio with the kind of heavy-duty equipment that he was using at the time. Awls, chisels, a razor blade and a small hammer lie on a table beside pencils, pots and a tube of Durofix glue.

Nicholson returned to England permanently in April 1971, shortly after the breakdown of his marriage with Felicitas Vogler (the author of the aforementioned photograph). It is unclear how much unfinished work he brought over from Switzerland. Of 38 works included in the October 1971 exhibition at the Marlborough, ten were dated to 1971. Though it would be surprising if all of these were completed in the four months before he left for England, several may have been started in preceding years and only completed then. The ‘ph’ (photograph) numbers inscribed on the reverse of all ten works – including 1971 (two squares and very green), which is numbered 1189 – suggests that they were completed in Switzerland, since the ‘ph’ numbering is that of Nicholson’s Swiss photographer Alberto Flammer.

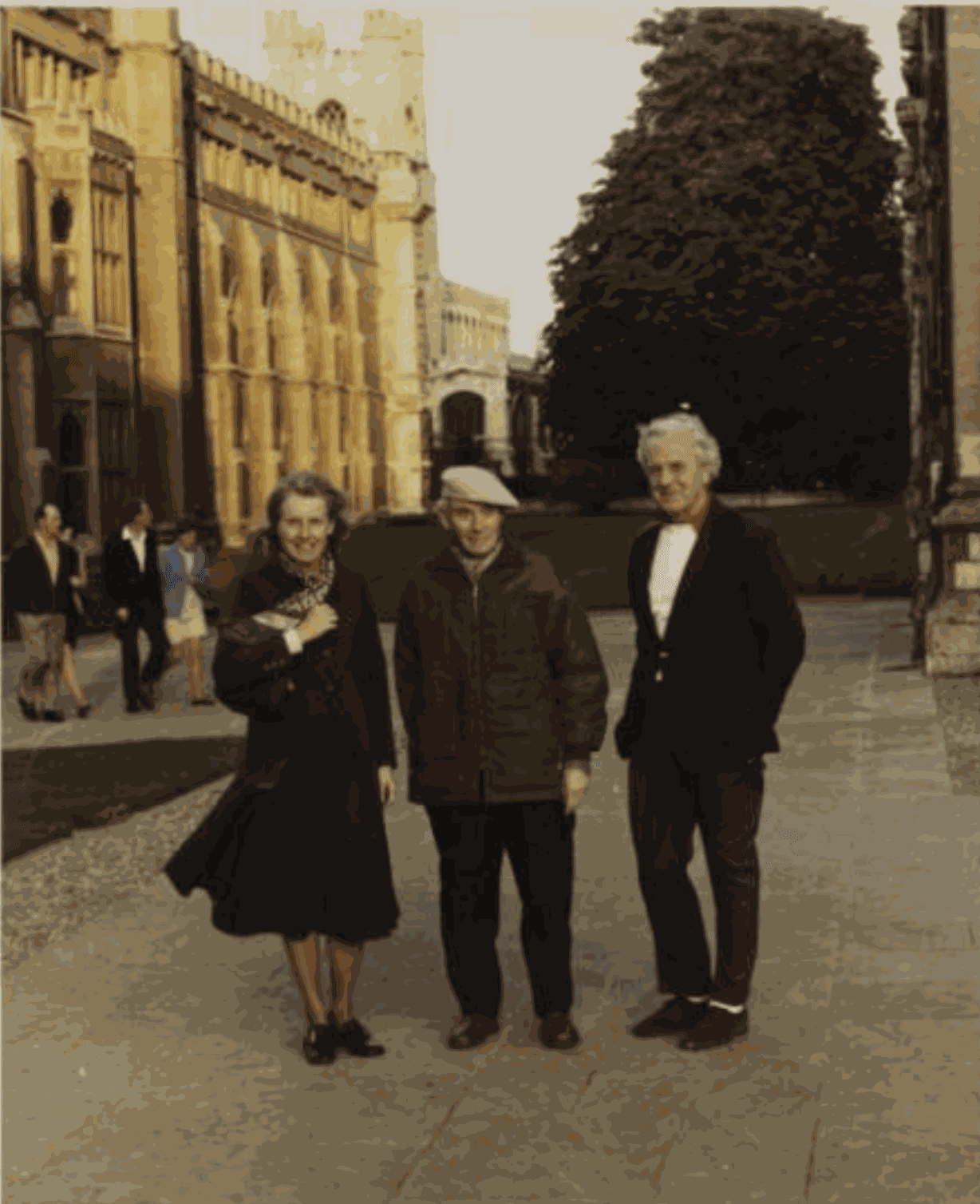

Back in England and with no place of his own to live, Nicholson called on his old friends Leslie and Sadie Martin. Leslie was a leading Modernist architect of his generation and Nicholson had collaborated with him and Naum Gabo to edit the publication Circle back in 1937. (There had also been a suggestion that Martin might design Nicholson’s new house in Switzerland, but the long-distance arrangement made this impractical.) Thankfully the Martins had a little space at their home in the village of Great Shelford, just south of Cambridge. The house was called The Flying Fox and Nicholson lived there until 1974, when he made his final move to a modest house-studio in Hampstead. Though he continued to work up until his death in 1982, Nicholson’s departure from Switzerland marked the end of his mastery of the carved relief. As such, the final Swiss reliefs of 1971 are the imaginative conclusion to a significant phase of the artist’s later career.