Described by his friend Sickert as ‘a perfect modern’, Spencer Gore’s early paintings belong to the world of Impressionism.

Between 1907 and 1910, Spencer Gore paid regular visits to his mother Amy and sister Kate in the village of Hertingfordbury, near Hertford. The Gore family was comfortably middle class, being distant relations of the Earl of Arran and (by marriage) the Earl of Bessborough and including among their number a bishop of Oxford and the first player to win the Lawn Tennis Championship at Wimbledon. Amy Gore lived at Garth House from 1904 and (as might be expected) it was a well-appointed property, complete with large sash windows and a tree-lined garden path. Both of these features appeared in Gore’s paintings of the period, along with many scenes of nearby Panshanger Park.

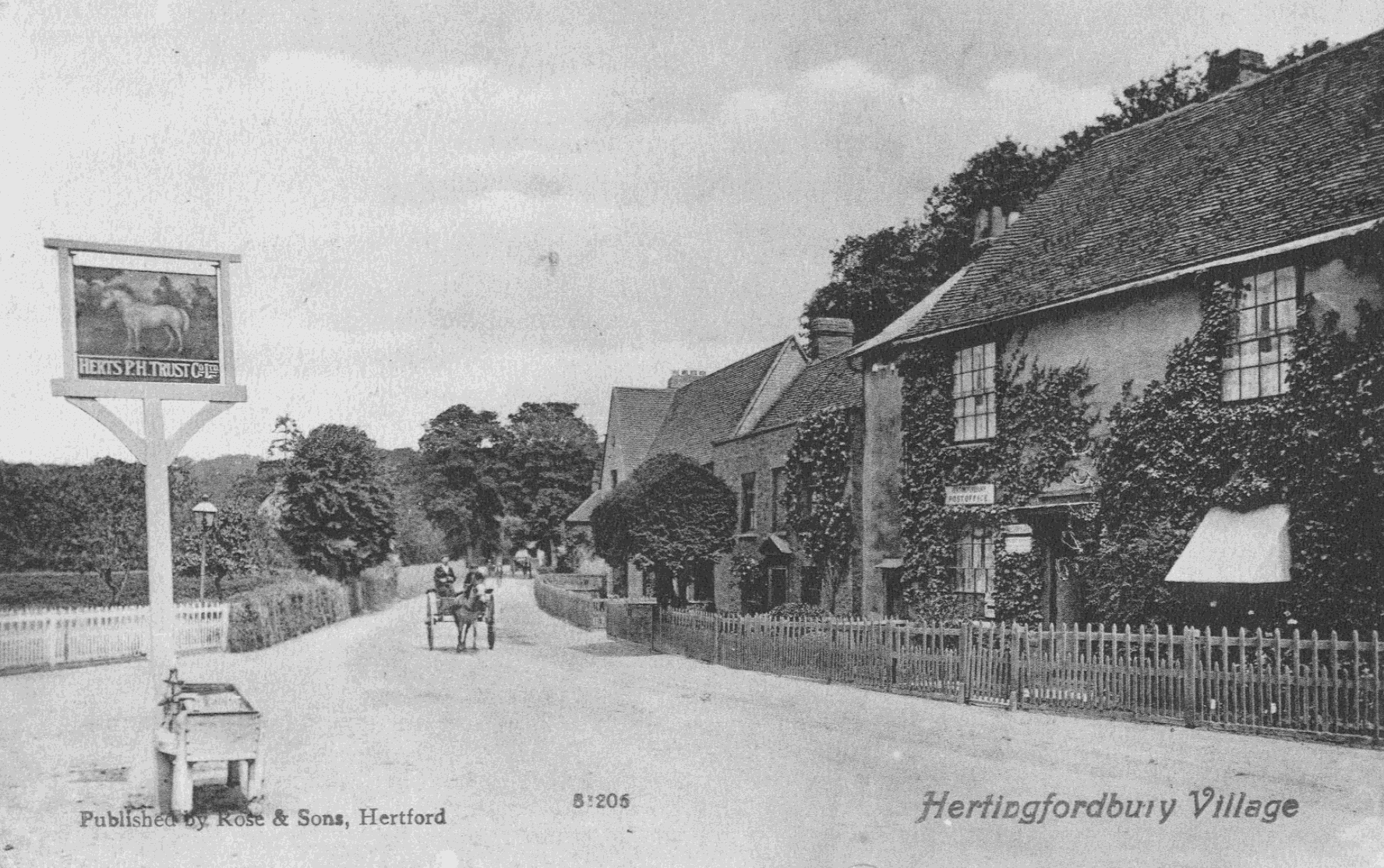

According to Domesday Book, compiled in 1086, the settlement of Hertingfordbury consisted of five villagers, six smallholders, eleven cottagers, four slaves and one Frenchman. To judge from Gore’s bucolic winter scene The White Horse, Hertingfordbury, which obliquely depicts the main thoroughfare nearly a millennium later, the village does not appear to have grown significantly in the meantime. The 1911 census shows that around 210 families were living in the parish – a relatively modest tenfold increase in the number of households since 1086. Despite its proximity to London, contemporary postcards suggest that the village still had an Edenic character at the time of Gore’s visits. Though today Welwyn Garden City is just four miles from Garth House, construction work on that town did not begin until six years after Gore’s death.

In a review of Anthony d’Offay’s 1983 exhibition of Gore’s work, selected by the artist’s son Frederick Gore and Richard Shone, Quentin Bell suggested that historical distance has made it difficult to appreciate the modernity of Gore’s work.

Looking again then, and remembering what landscape meant to art lovers who had been raised on a diet of [Benjamin Williams] Leader, it will be apparent that the harsh new-laid tiles of Letchworth, the fierce angularity of new built villas and the utter banality of a suburban railway station must have been sufficiently ugly and disconcerting in the year 1912. [...] Spencer Gore, in fact, encountered difficulties of which we are hardly aware.

At the time, English artists of ‘a modern character’ were tied into a network of stylistic influence which centred on Paris. Beside Sickert, who conversely admitted a debt to Gore’s colourful treatment of shadows, a key influence on Gore was Lucien Pissarro. Settling at Chiswick in 1897, Pissarro produced easeful and technically self-aware pictures following the model of the archetypal impressionist, his father Camille.

Taking as their subject the village church, the back garden, the farmyard or, indeed, the local inn, the Pissarros and their admirers transformed these pleasant scenes into challenging modernist visions. The novel aspect of their paintings came from broken brushstrokes, heightened colour (especially in the shadows), and the occasional use of textured impasto. Though the Post-Impressionist tropes of angular compositions and encrusted paint surfaces subsequently came to typify modernist practice, The White Horse, Hertingfordbury belongs to the moment before the Post-Impressionist wave came crashing in. In that moment, pictures like this were at the vanguard of modernist painting in England. A work of sensuous impressionist sensibility, it is distinguished by the atmospheric haze of wintry daylight and the dry, wisp-like brushmarks that evoke the unadorned tree branches. It aligns closely with a picture like Lucien Pissarro’s Hoar Frost, Chiswick.

An earlier undated drawing, donated to the Victoria & Albert Museum in 1936, shows that Gore’s loose handling of the trees at Hertingfordbury was preceded and underpinned by a rigorous observational method. Wholly devoid of schematic generalisation, the drawing shows the tree’s richly incidental branching pattern. This observational acuity was hard-won by Gore and his contemporaries in the Slade School’s life room. Far from being the spontaneous decision of a moment, Gore’s painterly manner followed from a thorough training. With an inimitable turn of phrase, writing after Gore’s premature death in 1914, Sickert described him as ‘a perfect modern’ who ‘built his astonishingly accelerated and fragrantly personal development on the good and stable foundation of a faithful, reverent and obedient studentship.’