Ben Nicholson produced only a small number of intaglio prints in his career. Each example is marked by pictorial subtlety and a craftsman-like understanding of tools and materials.

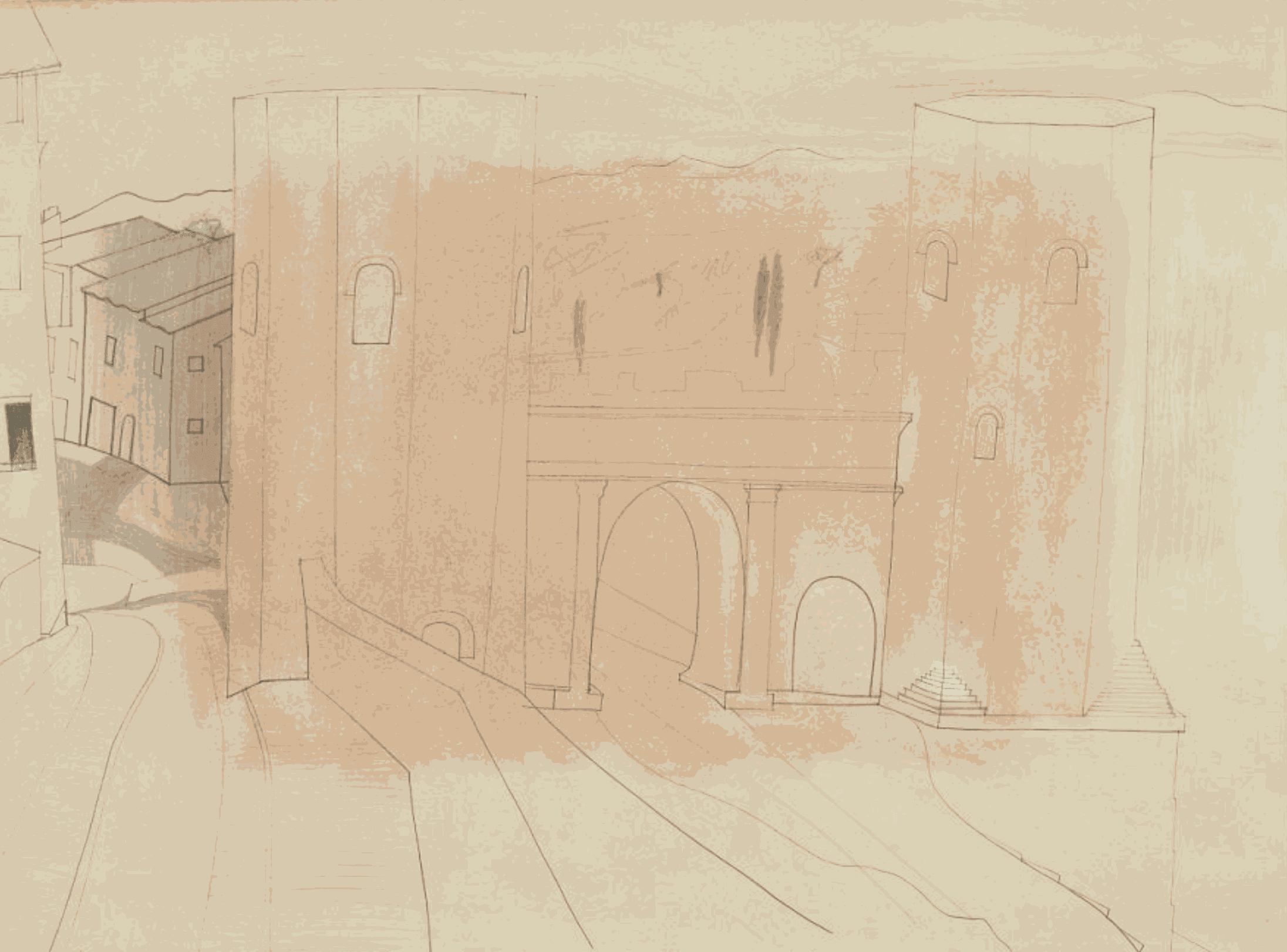

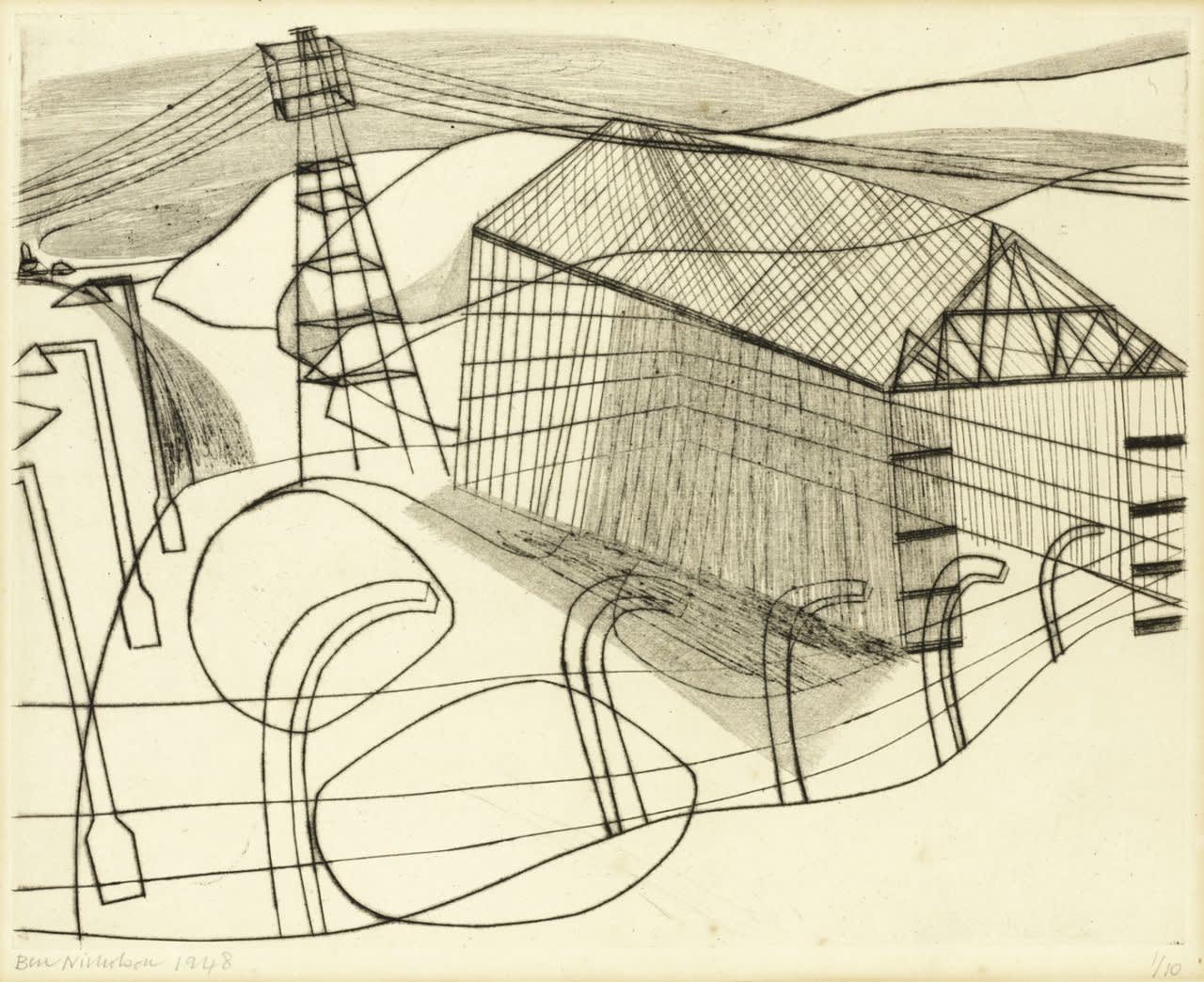

Like many acclaimed artists, printmaking was not Ben Nicholson’s principle creative outlet. Only after establishing a richly varied practice with oil painting and then carved reliefs did he start to experiment with intaglio printmaking. Between 1947 and ‘57 when he was living in Cornwall, he made ten drypoints which mostly depicted local subjects and still life. After he moved to Switzerland in 1958, he took up etching again for a short period between 1965 and ’68, when he favoured still life and architectural subjects found on his travels in Italy and Greece. In both his drypoints and his subsequent etchings, the subjects and technique of his prints were closely related to his drawings.

Both Nicholson’s prints and drawings use a distinctive graphic style – a fluent, wiry line which represents a building or a landscape in terse, imaginatively simplified compositions. Though the drawings show a mixture of graphic marks, including scribbled and soft-edged forms, both his prints and his drawings are defined by characteristic lines of singular intensity, applied with force and often running continuously to connect spatially disparate areas of the picture. The utensils differed, with a pencil for drawing and a steel needle for printmaking, but the technique for both was nearly identical. As he wrote of his etchings in 1968, ‘I suppose mine are really drawings on prepared copper’.

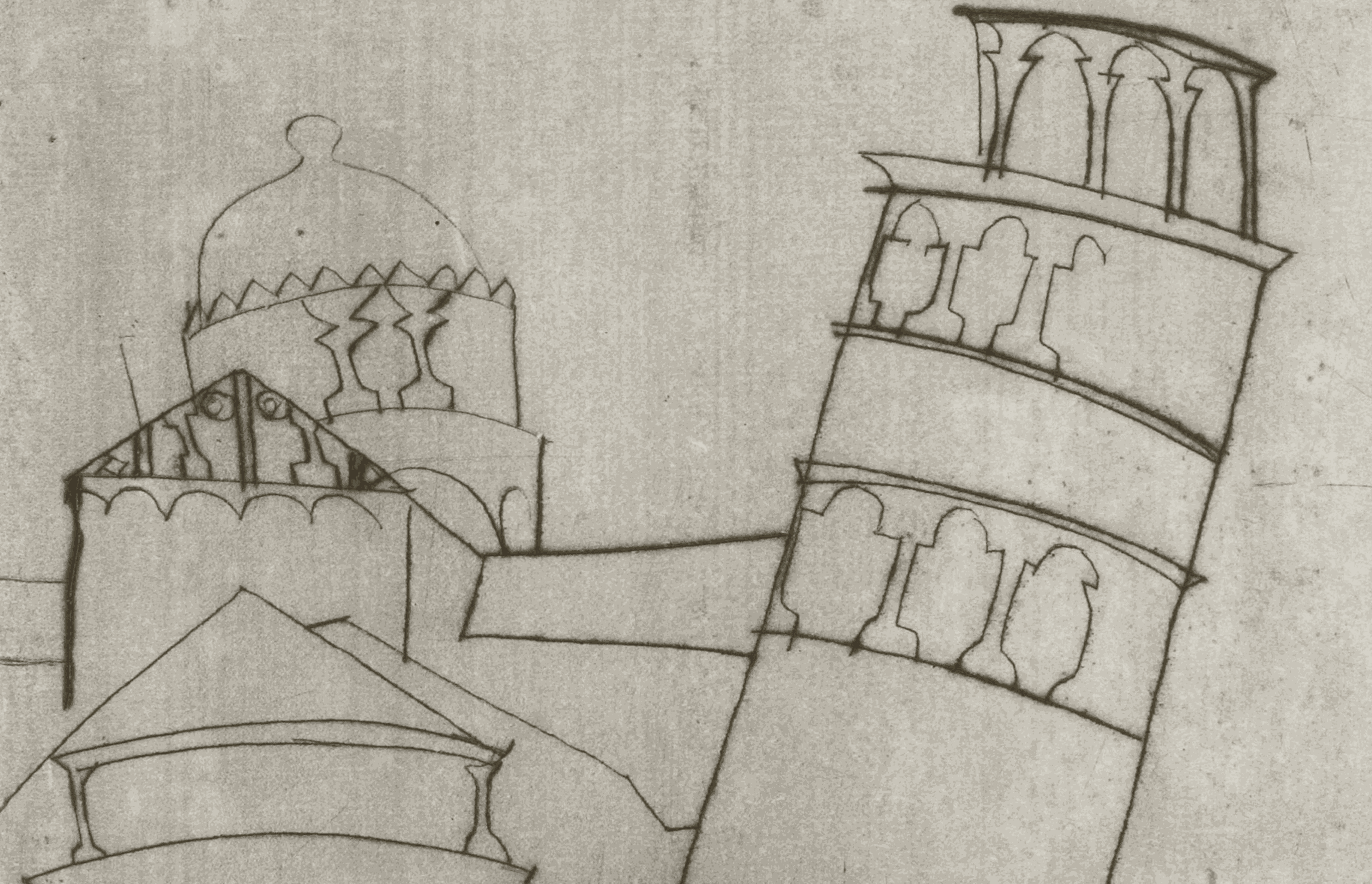

There is a subtle and important difference between etching and drypoint. Etching involves drawing with a needle onto a plate prepared with a wax-like, acid-proof ground, then biting the plate in acid to create grooves for inking and printing. By contrast, drypoint involves cutting into the plate directly using a sharp needle, with the effect of disturbing the areas on either side of the needle’s line. In printing, this disturbance registers as a rich inky burr around the intended line. Nicholson’s drypoint prints are typically smaller than his etchings, concentrated compositions showing the greater physical tension which the process required. In Pisa, a drypoint made in 1951, the lines of the print are enriched with a subtle tremor: the tension of the needle pushing across the plate is implicit. Nicholson’s later comments about etching seem directly applicable to this drypoint print.

There is a point also where I can cut into the metal in a line as straight as any ruler but with this difference, that the ruler will always rule straight whereas my hand line may at any moment decide to develop a curve – (it may decide) and if it does so then other lines must relate and may even develop a bigger curve […].

Where etching tends to give a consistent line (the plate is either exposed and etched, or concealed by the ground and not etched), the drypoint of Pisa’s cathedral and campanile shows a modulation in the firmness of the line. Deeper cuts with the needle resulted in a richer deposit of ink, as in the buildings close by at the bottom right-hand corner. By contrast, lighter incisions resulted in less fulsome lines. At the back of the composition, the cathedral’s dome is lightly indicated. In a subtle manipulation of pictorial means, Nicholson differentiated the depth of incisions to imply relative depth and nearness.

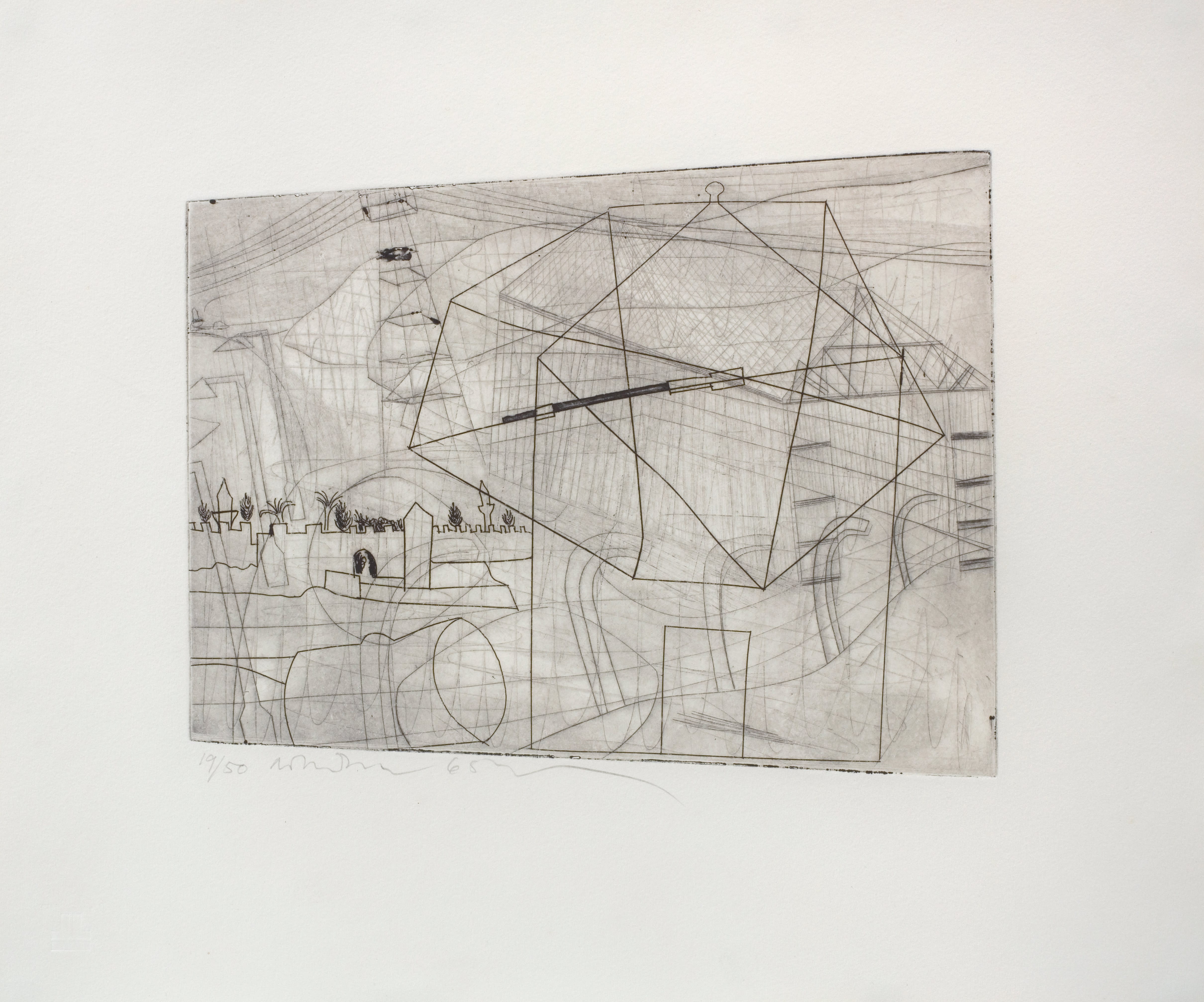

Though he was always supported by technicians who prepared and printed the plates, Nicholson took a close interest in the experimental possibilities of etching and drypoint. His etchings from the 1960s consistently used bespoke plates of an irregular quadrilateral shape. (This practice might be related superficially to the contemporary use of shaped canvases by younger painters like David Hockney and Derek Boshier.) In one case – Moonshine – he even used an exhausted drypoint plate as the basis for a new etching.

Drypoint plates produce a very small number of prints, with the burrs growing less pronounced with each press. By re-biting the old plate with etching, Nicholson produced an ingenious effect: a palimpsest where the underlying drypoint registers as a ghost beneath the firmer etched lines. The crepuscular landscape depicted in the print is washed by silvery moonlight, evoked with a subtle differentiation of tone in the printed lines – the faint lines of the drypoint are pale and almost translucent, while the etched lines are clearer and darker. Despite occasionally protesting his lack of professionalism in printmaking, Nicholson applied to reproducible media the same craftsman-like understanding of tools and materials that distinguished his efforts in every other medium.