For a blissful period of five years, the painter William Nicholson owned a rural retreat on the Sussex coast. The idyll came to a premature conclusion with the outbreak of war in 1914.

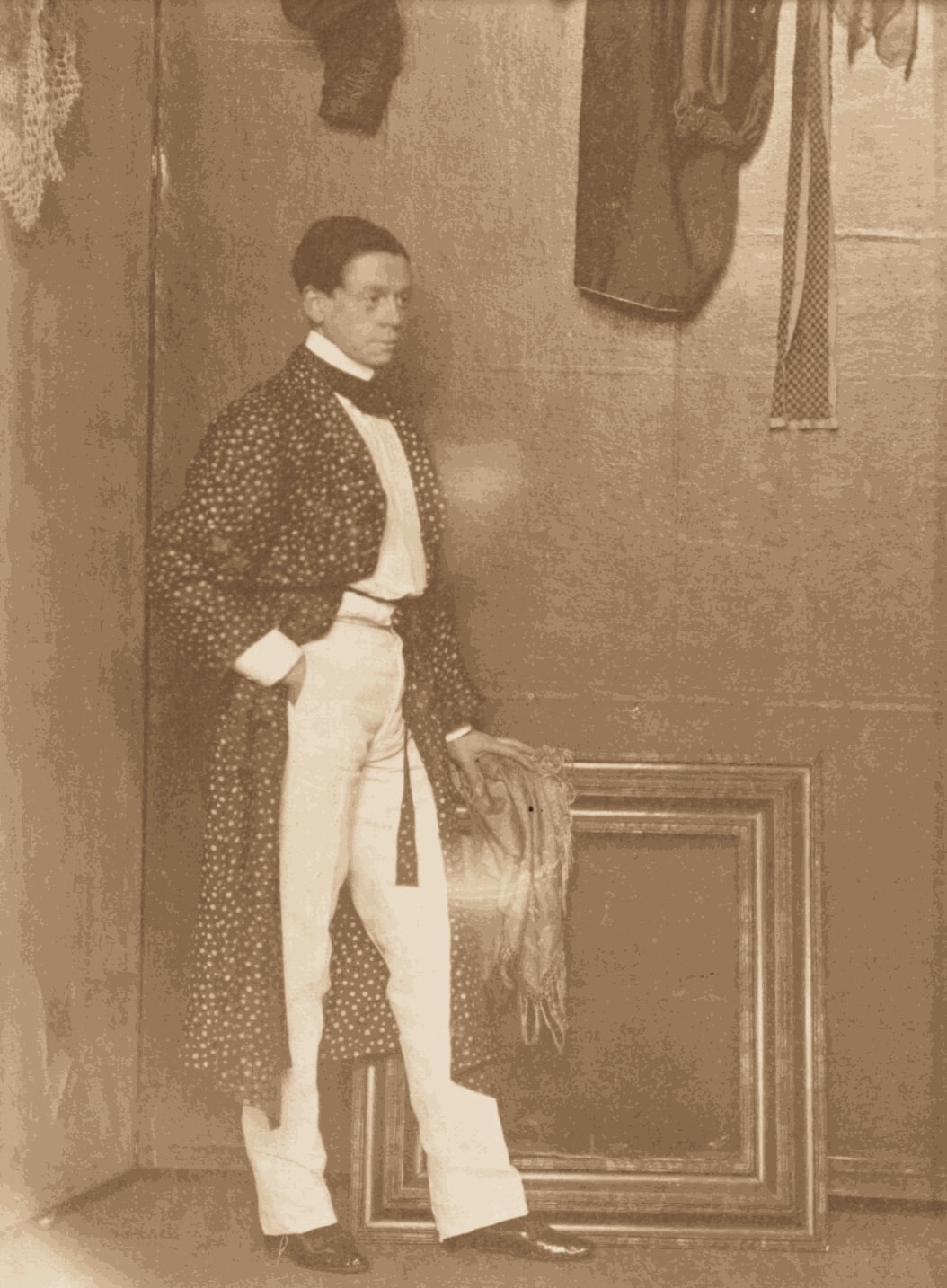

Though he had a taste for the fine things in life, Nicholson (1872–1949) was not always able to afford them. In his choice of clothes and his restless collecting habits, he often cut the figure of a Regency dandy. It was his impractical habit always to wear white trousers in the studio, he often wore a stock round his neck, pink lustred Sunderlandware stood on the mantelpiece, and there were prints by Dighton on the wall. His homes were always immaculately presented and carefully furnished, though they were often taken cheaply on the remaining years of a lease, as at 38 Mecklenburgh Square, or bought on impulse with little money to sustain the venture.

This was the case with The Grange at Rottingdean on the Sussex coast, a former rectory which William and his wife Mabel bought in 1909. Over the next five years, the weekends and holidays were spent away from London on leisurely painting visits, with both William and Mabel executing pictures in and around the house. It was a grand property, since repurposed as the local museum, and it appears in a number of William’s paintings. It was later featured in an issue of Country Life, by which time Edwin Lutyens (a friend of Nicholson’s, incidentally) had added a small extension for a subsequent owner.

Paul Nash was a Slade friend of William and Mabel’s son Ben, and in his unfinished autobiography he recalled the great stylishness of both William Nicholson and his properties in London and Rottingdean.

William Nicholson was then particularly conspicuous as an artistic personality, no other painter being quite so brilliant an executant. All his work had an air of easy mastery and good quality […]. I seem to remember a good many effects in the Nicholson home which ecstatic interior decorators had ‘invented’ twenty years earlier. […] Blue ceilings, black mirrors, maps on the walls. […] I went to spend a week at Rottingdean where the Nicholsons had a charming house. Here again was evidence of the amusing family taste applied with a slightly different flavour to adjust it to country life. Everything was bright and gay and calendared.

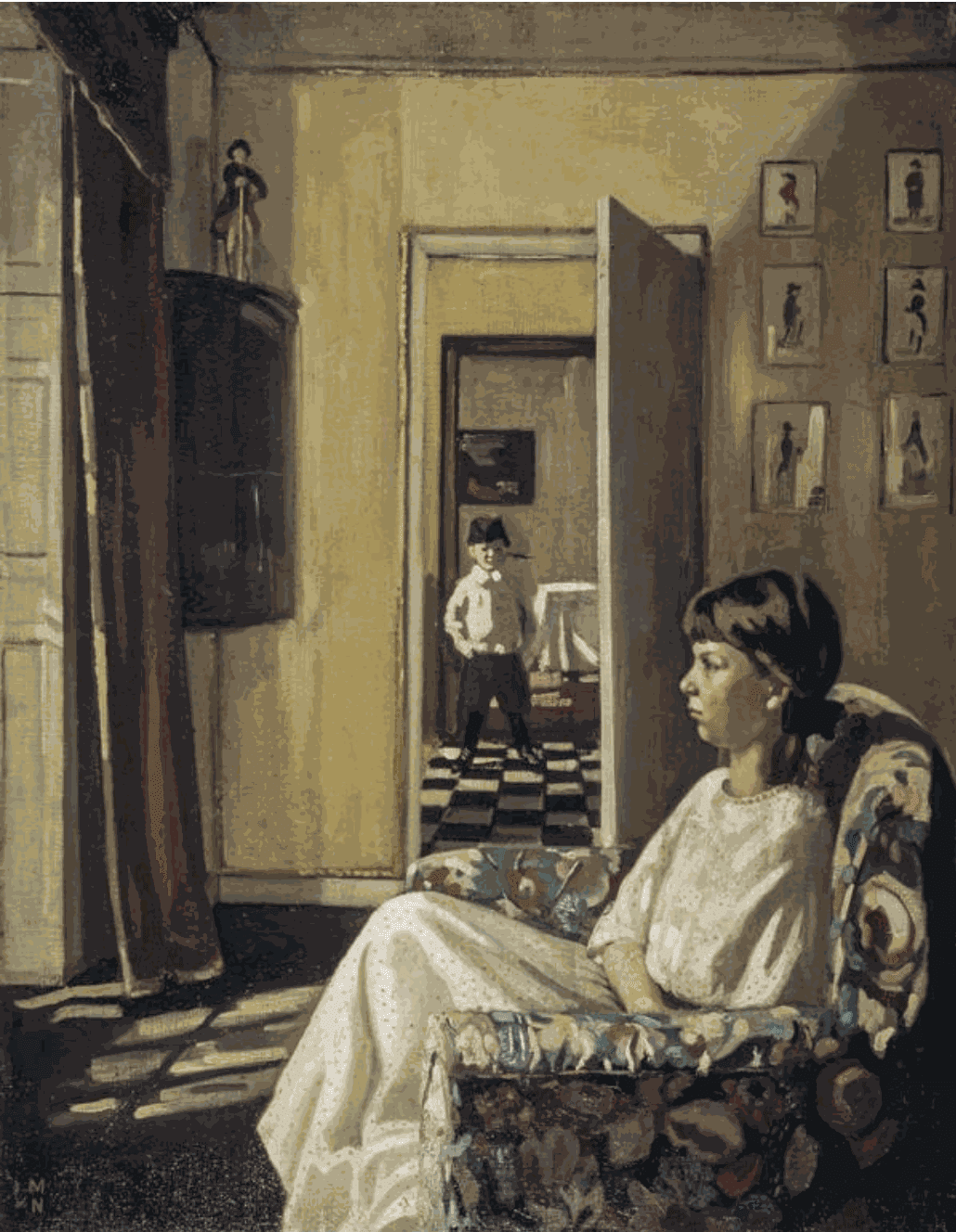

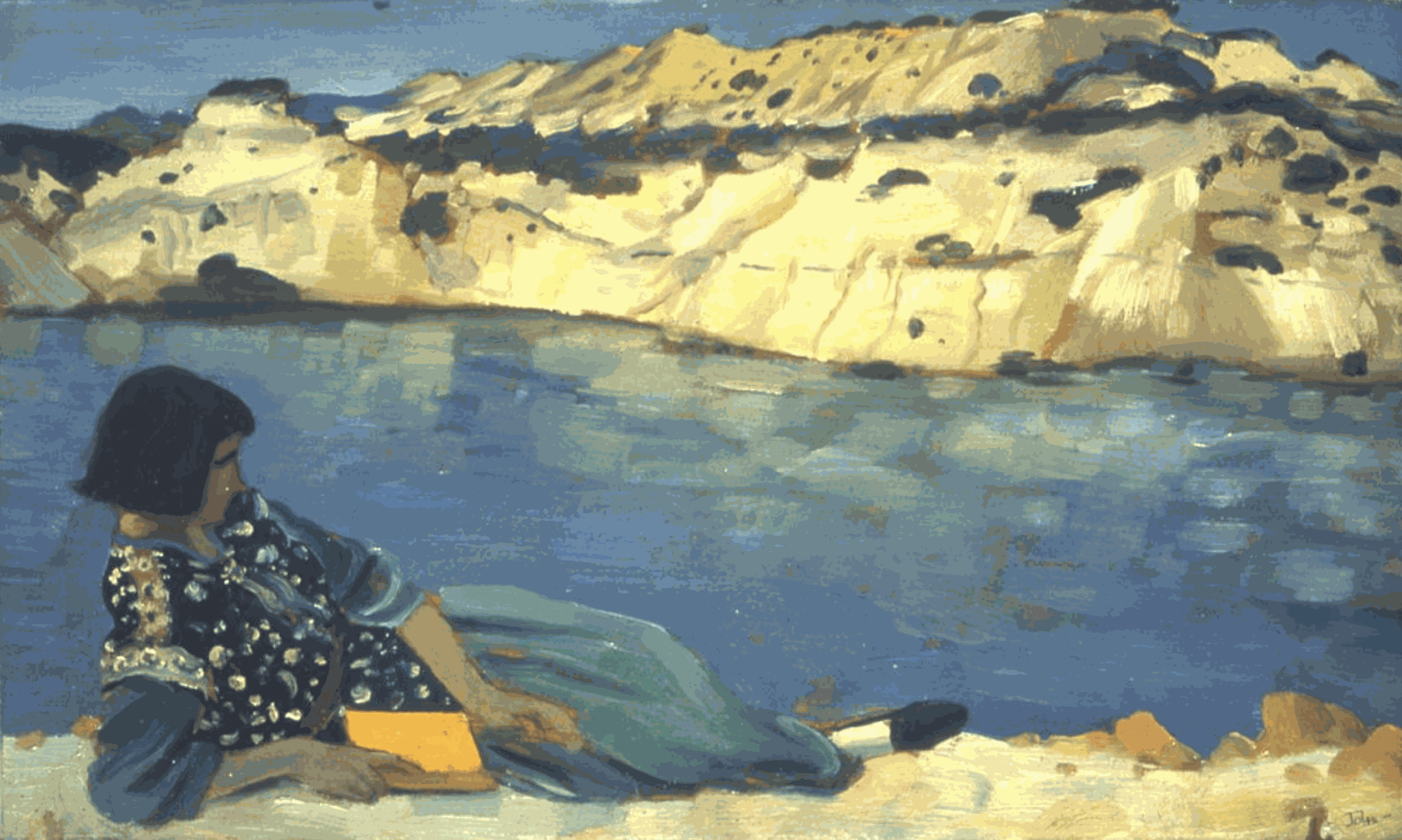

One of seventy or so paintings that Nicholson completed in Rottingdean, The Grey Shawl belongs to a small group of figure paintings by the artist which introduces a landscape at the picture’s lower edge. The work was owned by the Earl of Harewood from 1965 until his death in 2011. Just beyond a squat clifftop house at lower left, a localised area of impasto suggests a high sun shimmering on the sea. Along with its pendant The Blue Shawl and other portraits like Mrs Stafford of Paradise Row, The Grey Shawl uses an elevated perspective and treats this sliver of the coast as a framing device. The effect of suppressing the horizon line is to activate the rest of the background – a vast, cloud-dappled sky which wraps around the figure.

Like John Singer Sargent and other commercially popular artists of the day, Nicholson fought to escape the deadening imposition of portrait commissions. To make this work more interesting, he frequently introduced complementary aspects from his preferred genres – still life and landscape. (In his Portrait of Mrs Curle from 1906, he struck upon the modish idea of depicting the lady at table with her breakfast things.) The inclusion of Rottingdean’s coastal landscape in a work like The Grey Shawl is less obviously supplementary, however. The sitter is anonymous and the combined figure-landscape imagery belongs to a genre-straddling typology popular at the time, other exponents of which included Augustus John.

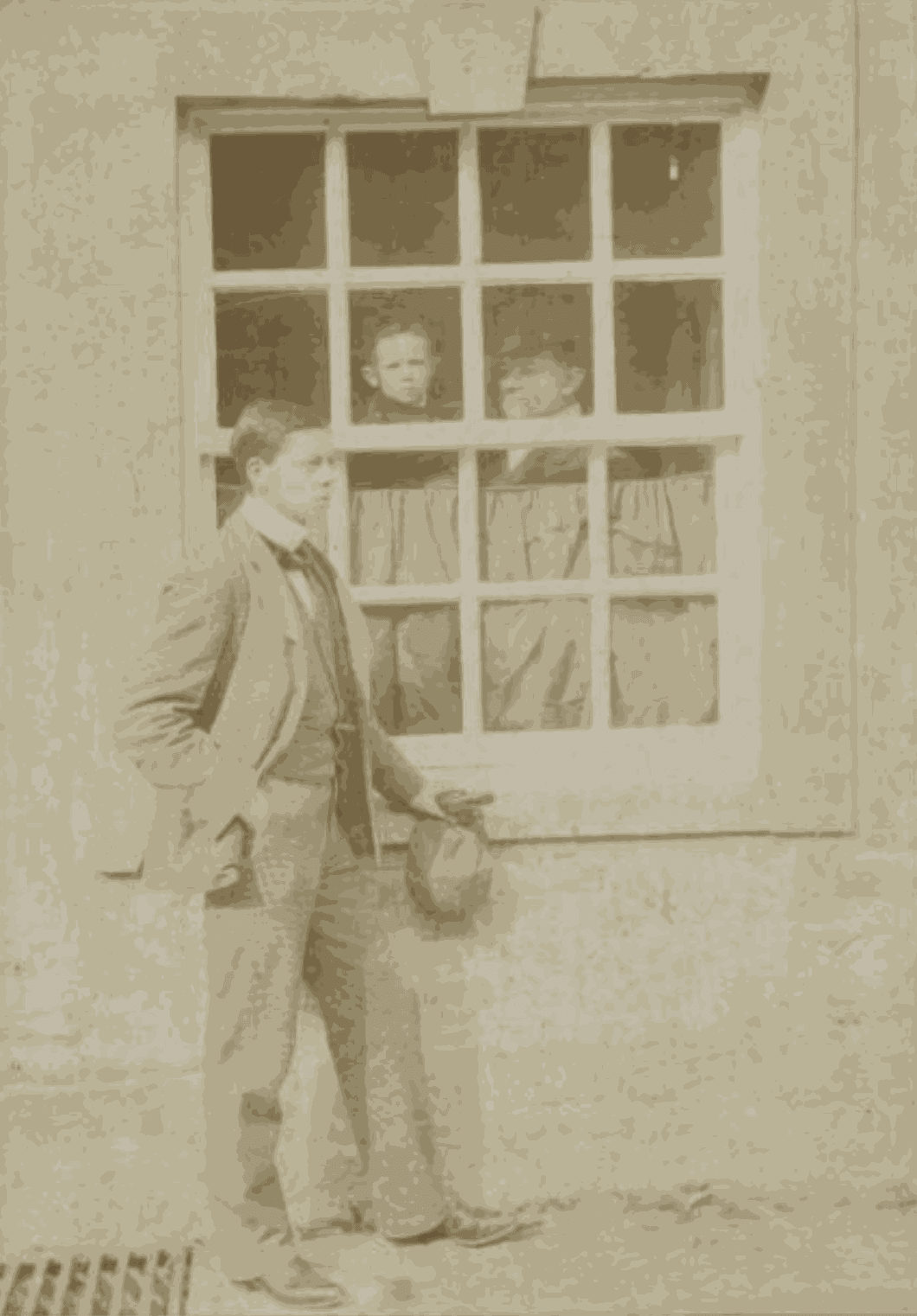

William and Mabel’s visits to Rottingdean were not just painting trips. Their four children would accompany them and a strong sense of family fun emerges in memoirs of the time. Nicholson’s painter friend William Rothenstein also stayed in the village occasionally, and he recalled that ‘our children made friends with [William’s] children’. A letter from the wit Max Beerbohm, another Rottingdean habitué, continues the story.

I am so glad you like the Nicholson troupe, they are somehow more like a troupe than a family - Nancy standing with one spangled foot on Nicholson's head, Ben and Tonie branching out on tip-toe from his straddled legs, Mabel herself standing at the wings, holding the overcoats.

Though the Nicholson and Rothenstein children spent time together in Rottingdean, it is not entirely clear that they made friends. Ben Nicholson later described a visit from Rothenstein’s son John (who later served as director of the Tate Gallery between 1938 and ’64).

One afternoon Lady Rothenstein (a very nice person) appeared with her son in order to pick up one of our family on the way to a children’s party. And there was little Johnny Rothenstein all togged up in an Eton suit, washed and brushed and ironed and combed and not a hair out of place and a gardenia in his buttonhole. My sister, Nancy, who did not care much for little Johnny, took a hose, climbed up onto one of the gate pillars and hid behind the stone ball at the top and as he came out she turned the hose full onto him and soused him from head to foot.

Tate Gallery Archive 8717/5/8/2