Despite being closely related to contemporary Kitchen Sink realism, Peter Coker’s ‘meatscapes’ of the 1950s emerged from a direct engagement with the original realist painter: Gustave Courbet.

Almost immediately after finishing his post-graduate studies at the Royal College of Art in 1954, Coker (1926–2004) entered the public imagination as an artist of talent. His acute realist sensibility, the open-grained quality of his painting, and the exacting simplicity of his imagery came to light at his first solo exhibition in January 1956. It was held at Zwemmer Gallery, around the corner from the famous bookshop on Charing Cross Road, and was dominated by Coker’s paintings of animal carcasses. Most depicted unplucked chickens and hares. Fish with Grill exemplifies the main characteristic of these ‘meatscapes’: a scabrous impasto, paradoxically uniform across the picture surface while successfully evoking in turn the distinctive textures of fish, a wooden table and assorted objets.

Critics were quick to compare Coker’s distinctive table top still lifes with the ‘Kitchen Sink’ manner. The mid-1950s was the zenith of its influence and in the autumn of 1956 its main exponents represented Britain at the Venice Biennale. The visual similarities between the work of Coker and those artists – Bratby, Middleditch, Greaves, Smith – are plain to see. Shared features were the general absence of starched table linen, the exposure a rough-hewn work surface, a gathering of kitchen equipment, and the self-consciously haphazard arrangement of those objects.

However, a comparison with Kitchen Sink art only explains so much about Coker’s still life from the period. In several respects, Coker’s paintings cultivated a very different approach to picture-making. One distinguishing feature was his attitude to perspective. Where an archetypal Kitchen Sink painting like Bratby’s Still Life with Chip Frier composed the scene from a three-quarter-length angle, approaching the table from a corner and including the chair legs and the space around it, several of Coker’s works ‘tip up’ the table top and make it stand up in parallel to the canvas. This original approach to still-life composition had been pioneered since the 1930s by Ben Nicholson, who sought to reconstruct his subject-matter in a witty play of intersecting outlines, as well as by William Scott, whose imagery of long-handled frying pans chimes with Coker's prosaic still-life theme.

By contrast with Nicholson's still lifes, Coker loaded his paintings with detail and bold textures. The outcome might be regarded as a successful variation on the Cubist notion of an object-like picture, in which the painted table surface shows not just visual but material similarities to the real thing.

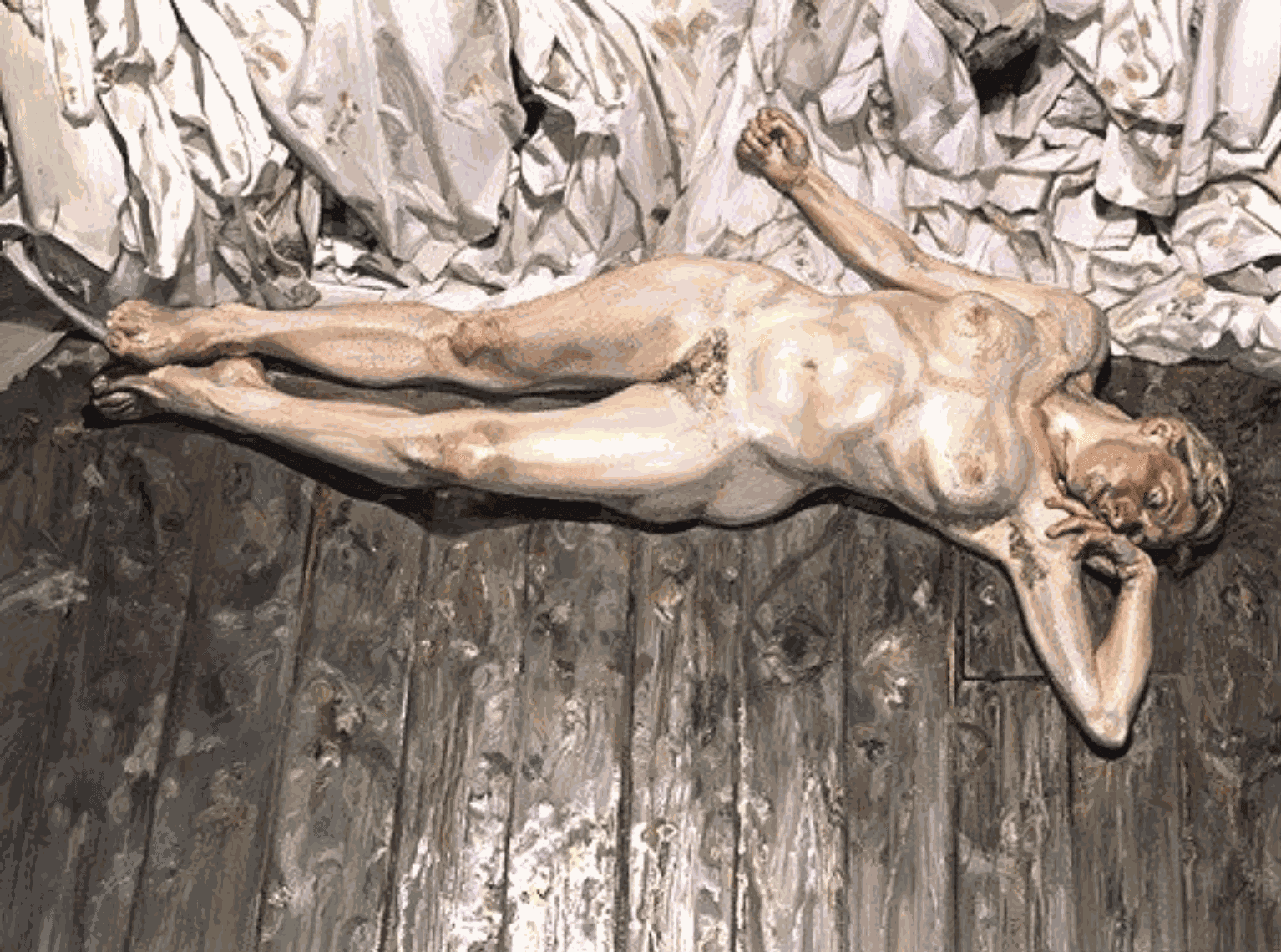

In Fish with Grill and several other ‘meatscape’ still lifes by Coker, the wooden planks of the table run continuously through the length of the picture, from top to bottom or side to side. A perennial source of interest to painters of a realist sensibility, bare floorboards have occasionally been made a painting’s chief subject – as they were in Gustave Caillebotte’s Floor Scrapers (1875), for example. Continuous flat pieces of open-grained wood are a rich source of visual interest, variously reflecting or absorbing the light and displaying a more or less irregular pattern of knots. Following Coker’s intense scrutiny of the table’s wooden boards, another post-war realist painter adopted this as a technique for activating negative space. Floorboards were prominent in Lucian Freud’s work from the late 1960s onwards, each one fastidiously observed and delivering on his claim to paint a ‘ground’ rather than merely a ‘background’.

Writing in The Journal of the Royal Society of Arts from May 1956, the critic Neville Wallis noted the inclusion of Coker’s ‘butcher’s carcasses’ at the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition. He suggested that the paintings were ‘that dour, relentless mode introduced soon after the last war by the French realists’. Wallis was perhaps thinking about the paintings of Balthus or even Francis Gruber. Though French in origin, Coker’s personal creed of realism in fact grew from his awareness of Gustave Courbet, the nineteenth-century originator of ‘realism’. Coker first saw his work in person on a visit to Paris in 1949. The spirit of a painting like Fish with Grill derives from Courbet’s own paintings of fish, and the French artist was to be a point of continuing reference for Coker throughout his long career.