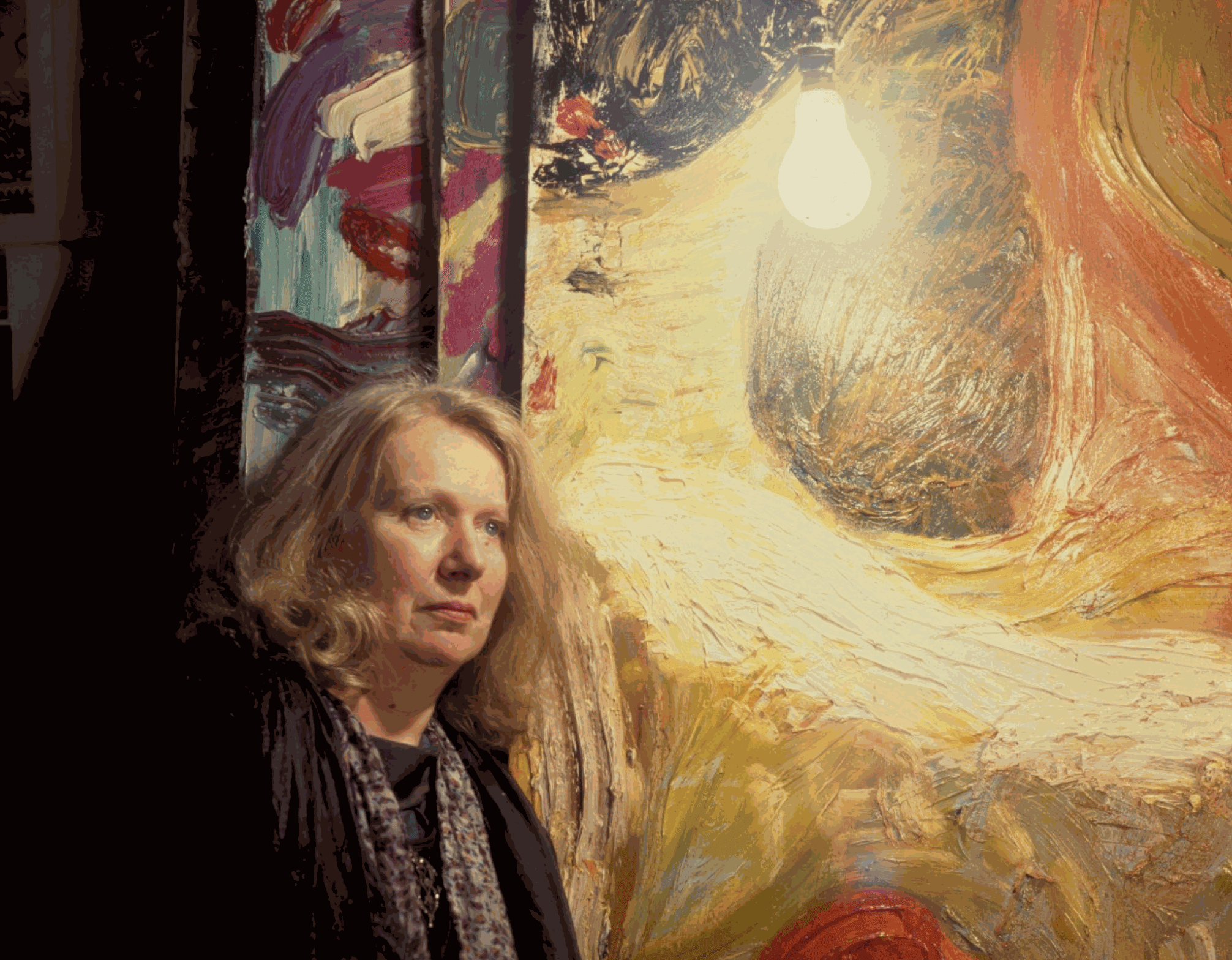

One of the most independent British abstract painters of the later twentieth century, Gillian Ayres’s career spanned the swinging ‘sixties and ‘nineties Britpop. Her work is reflective of both, and much else besides.

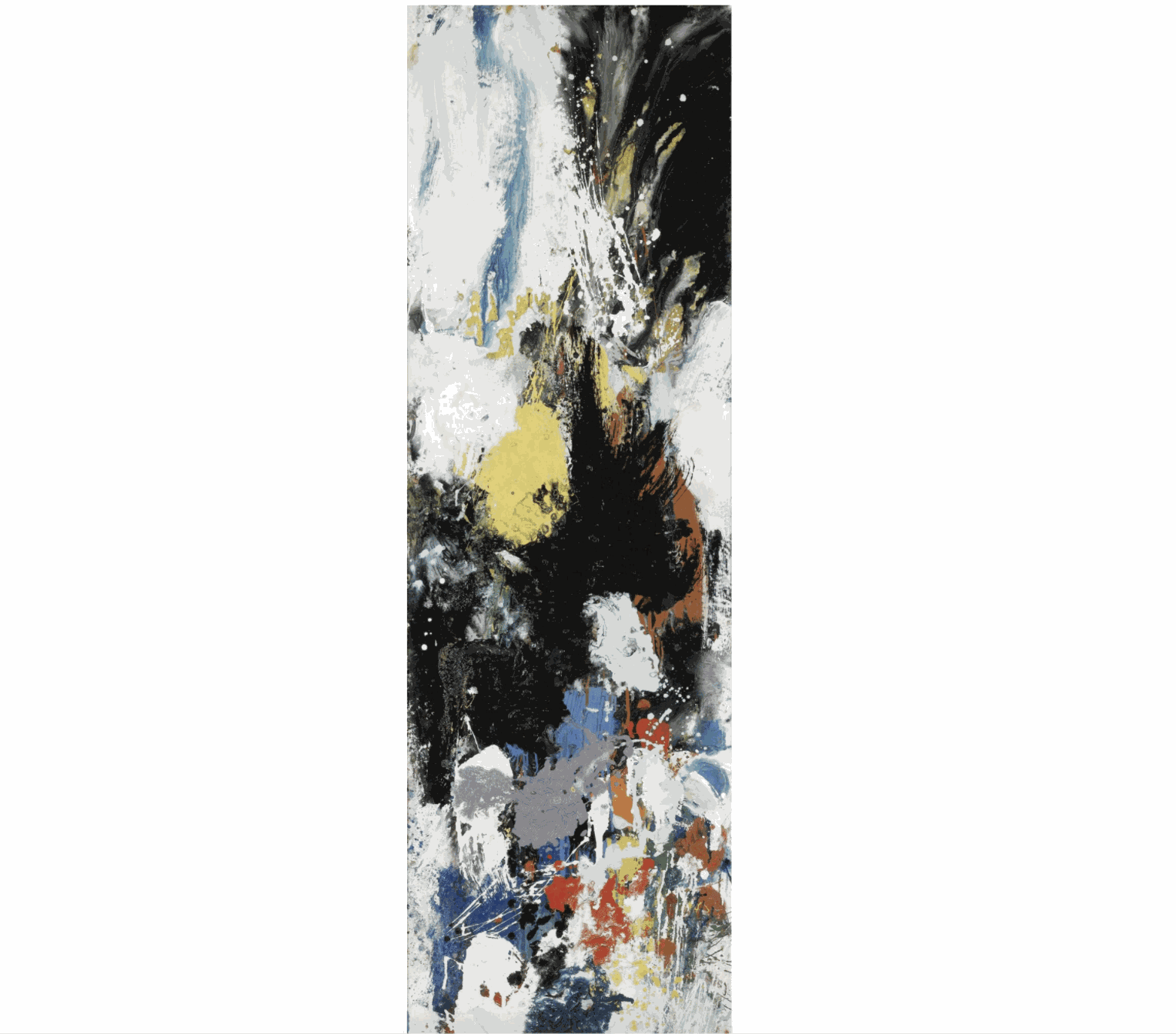

Ayres’s (1930-2018) career was underway even before London had started to swing. Working three days a week at the AIA Gallery in 1951, she slowly began to accumulate stimulating examples of abstract art. Roger Hilton was connected with the gallery and Ayres later claimed that he was the first person ‘really’ to speak to her about painting. His gestural, painterly approach to abstraction, akin to that of Peter Lanyon and Terry Frost, was a formative early example to her. Belonging to the next generation as she did, however, progressive French and American art exercised a strong pull on her imagination. Temporarily rejecting the unwanted refinement conferred by brushes, she achieved her first distinctive visual idiom in the later 1950s with narrow vertical canvases of overlapping splashes. These often colourful paintings were awarded inscrutable titles like Abstract, Tachiste Painting, and Distillation.

Though she eventually returned to the use of brushes, improvisation and spontaneity remained central features of her approach to abstract painting. Nevertheless, it was not until the early 1980s that she emerged with a new and highly distinctive idiom of her own, and in the meantime she forged a career as an art college teacher, beginning at the Bath Academy of Art where she worked between 1959 and 1966. An extraordinary innovation of Lord Methuen, the academy was a residential college and from 1946 was based at his ancestral home, Corsham Court. The academy’s pre-eminence largely stemmed from the quality of its teachers, which (aside from Ayres) included William Scott, Peter Lanyon, Jack Smith and Howard Hodgkin.

From Corsham, Ayres went on to teach at St Martin’s and Winchester. Not until 1981, a year after her fiftieth birthday, was she free to leave teaching and spend all of her days painting. Seizing the opportunity, she moved to Wales the same year and remained there until 1987. She then went to live in an obscure valley on the border between Devon and Cornwall, and remained there for the rest of her life. In one of her postmodern fairy stories, Ayres’s friend the novelist Angela Carter evoked a place of comparable magic and isolation.

The clearing was cluttered with dead leaves, some the colour of honey, some the colour of cinders, some the colour of earth. [...] The brown light of the end of the day drained into the moist, heavy earth; all silent, all still and the cool smell of night coming. The first drops of rain fell. In the wood, no shelter but his cottage.

The secluded settings in Wales and Cornwall were not incidental to Ayres’s work. Speaking to Mel Gooding in 2000 about an unintended response to landscape, she said ‘I don’t know how these things enter my work… they can put you on a high perhaps. […] I don’t mind if things get into me.’ Though she was reticent to explain how her surroundings affected her paintings, a loose connection evidently existed between the two. In other respects, her rural home in Cornwall certainly had more practical implications. Living at the end of a steep track shrouded by dense woodland, her paintings had to be carried by hand to the main road ahead of her London exhibitions, since the couriers’ lorry was often too large to attempt the drive.

Though some of her work was of great size, occasionally reaching three-and-a-half meters in width, her lasting importance is founded on smaller, more concentrated paintings of the 1980s and ‘90s. After a period of using acrylic in the 1970s, she returned to oil paint in 1978 and began making exuberant works of bright colour and immaculately distinct brushwork. Though she always created a rich impasto, her colours and brushmarks are clearly defined, never growing faint or muddy from overworking. Her canvases of this period were often square or circular (a todo format), and these elementary shapes often found expression as non-representational figures within the painting. Choo Choo includes several roundels, for example.

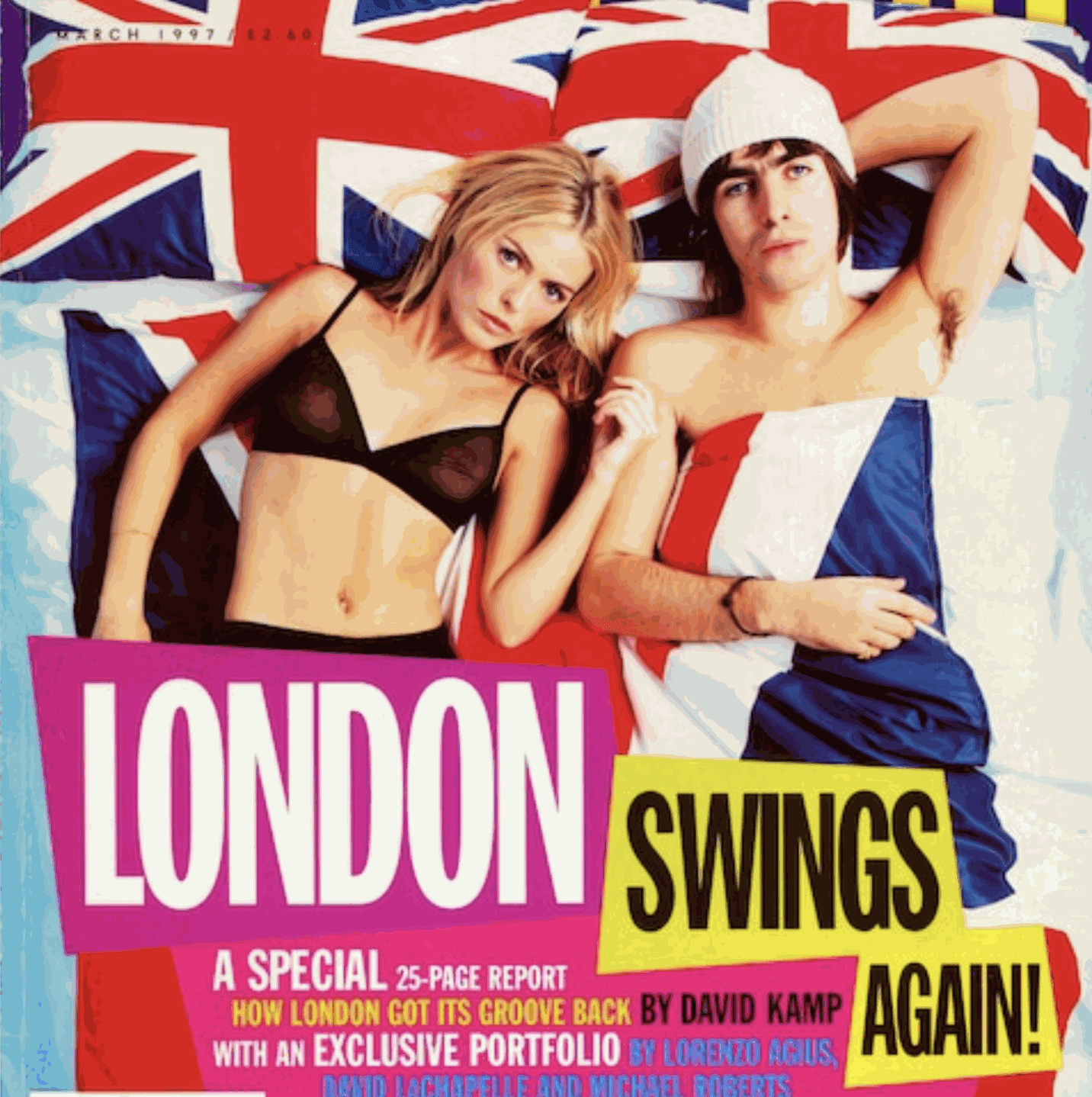

Ayres started to receive more sustained public attention at this time, beginning with an Arts Council exhibition at the Serpentine Gallery in 1983. Though it has yet to be acknowledged, she might be described along with Michael Craig-Martin and others as a significant precursor to the Young British Artists who emerged in the 1990s. Though she herself may have disputed it, a work like Choo Choo from 1996 has a certain type of glamour and verve, and it sits comfortably in line with the contemporary Britpop moment and its intoxicating cocktail of transparent bras, Blairite optimism and Blur.