Born in Austria and displaced to Britain by the Nazis, Lucie Rie became one of the leading potters working in the second half of the twentieth century. Her ceramics were admired for their distinctive surface patination, decorative incisions, and often flamboyant silhouettes.

Rie gained an international reputation for her ceramics early on, receiving a silver medal at the Paris Exposition Internationale in 1937. The following year, however, she became a refugee, fleeing from Austria just before the Anschluss with Nazi Germany. She and her husband came to Britain and, with the help of their friend, the architect Ernst Freud, found a small studio at 18 Albion Mews, Paddington. (Incidentally, this was a half-an-hour’s walk from where Ernst’s artist son, Lucian, acquired a studio in 1943.)

Rie was a lifelong advocate of crafting ceramics at the throwing wheel, a defining feature of British ‘studio pottery’. She worked in the same Paddington studio until her death, whereupon it was dismantled and recreated in the Potteries Museum & Art Gallery, Stoke-on-Trent. At the time of her arrival in Britain, however, there was little interest in her work. Throughout the Second World War she made little other than buttons, selling them to the fashion trade whose button factories had been requisitioned for the war effort.

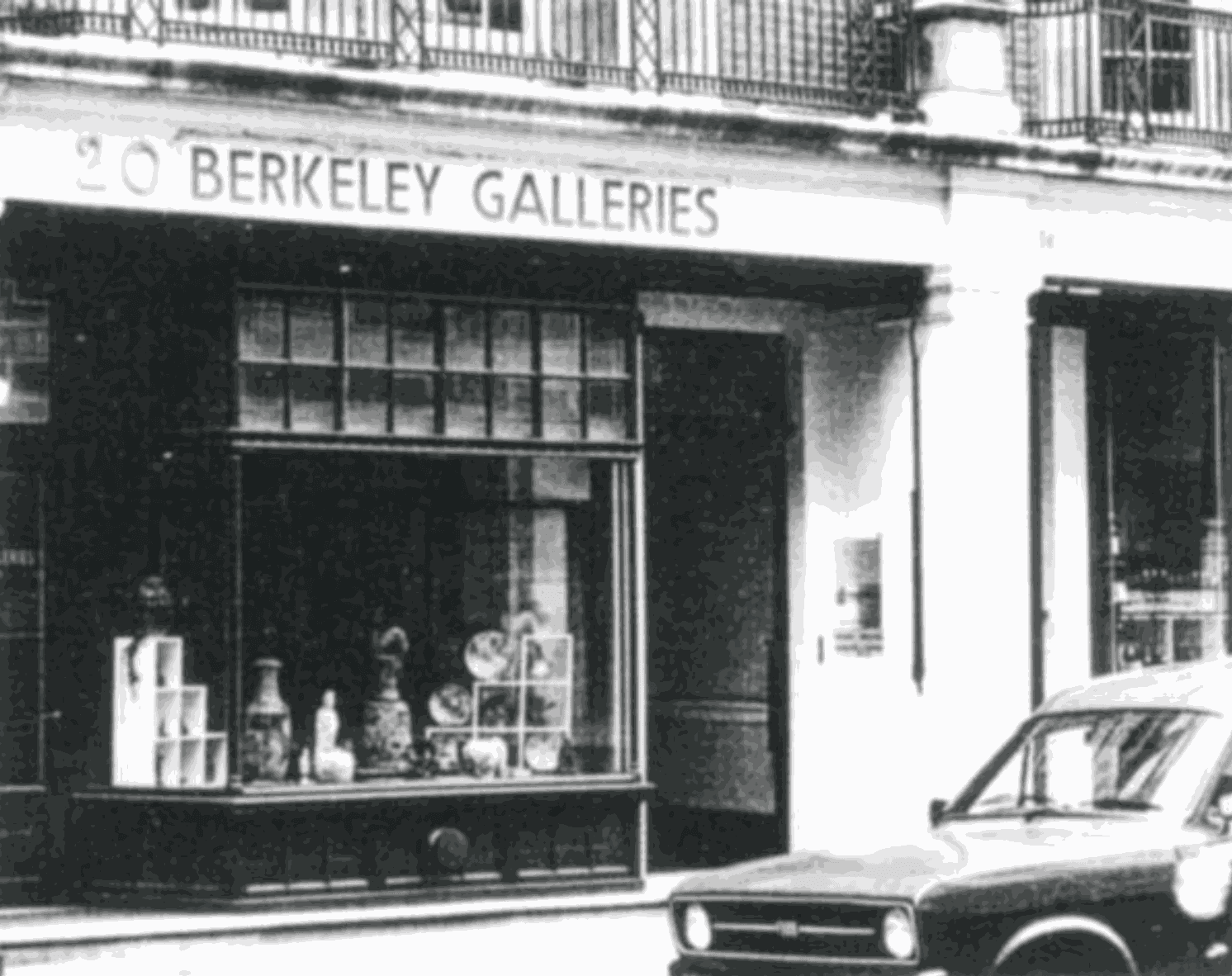

After the war, Rie recovered her enjoyment of more developed ceramic forms and began exhibiting regularly at the Berkeley Galleries, which also showed the work of Henry Moore, Bernard Leach and Oskar Kokoschka, as well as a wide variety of ethnographic artefacts (then regarded as ‘primitive art’). Not until an Arts Council retrospective of her work in 1967 did her fame begin to grow. This was followed by honours (a CBE in 1968 and a DBE in 1981) and further exhibitions at the V&A in 1982 and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1994, the latter of which was held jointly with Hans Coper who worked alongside Rie between 1947 and ‘58.

From the late 1970s, Rie’s work became increasingly varied and free, with several vases receiving only localised areas of glazing. Convention dictates that a potter should fire their decorative vessels twice: once to fix the clay form and again to fix the glaze. Rie would use only a single firing, however, applying a glaze to fragile ‘greenware’ – pottery which has been shaped but not fired. This heightened the risk involved in the firing process, allowing for the possibility of simultaneous structural and decorative failures in the kiln. The finished surviving works are unmistakeable for their virtuosity. The example illustrated immediately below not only retained its complex shape, but emerged from the kiln with a subtle combination of decorative incisions (‘sgraffito) and bronze-brown manganese glazing, which has been allowed to bleed along the inside lip of the rim, creating an organic effect in contrast to the object’s overall effect of terse precision.

One of the most significant private collections of Rie’s work belonged to Robert and Lisa Sainsbury. They had met Rie in the 1950s and her work inspired them to collect other ceramics, including those of Coper. The Sainsburys had eclectic tastes, amassing a wide variety of objects, including fine pieces of medieval religious carving, and patronising many contemporary artists like Francis Bacon. All of the 257 works (including many buttons) which they acquired from Rie are now the property of the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts.

In 2017, a large exhibition of British studio pottery was held at the Yale Center for British Art in New Haven, Connecticut, and the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge. The display was divided into different types of vessel (moon jar, vase, bowl etc.) and drew attention to the continuity and ongoing success of this tradition, with the inclusion of work by artists like Edmund de Waal and Grayson Perry. Despite the obvious handicraft aesthetic of these objects, the exhibition also demonstrated the fine art qualities of works like Rie’s vases. Such pieces have a classical self-containment, emptied of functional purpose and loaded with fine decorative qualities, not least the subtle coloration and linear refinement which transcends much other studio pottery.