After his first visit to India in 1964, Howard Hodgkin continued a life-long relationship with the country. Near the end of his life, when asked why he became so attached, he said, ‘it was completely exotic. It couldn’t be further away from living in Shepherd’s Bush, as I was then.’

Over the course of nearly thirty visits in his lifetime, Hodgkin travelled widely across India. On one visit in 1978, he went for the first time to Ahmedabad in Gujarat.

I was invited by the Sarabai family to work there. They’re a family of mill owners, who live in a Le Corbusier house in the middle of a Douanier Rousseau garden, surrounded by a high wire fence, in the middle of Ahmedabad.

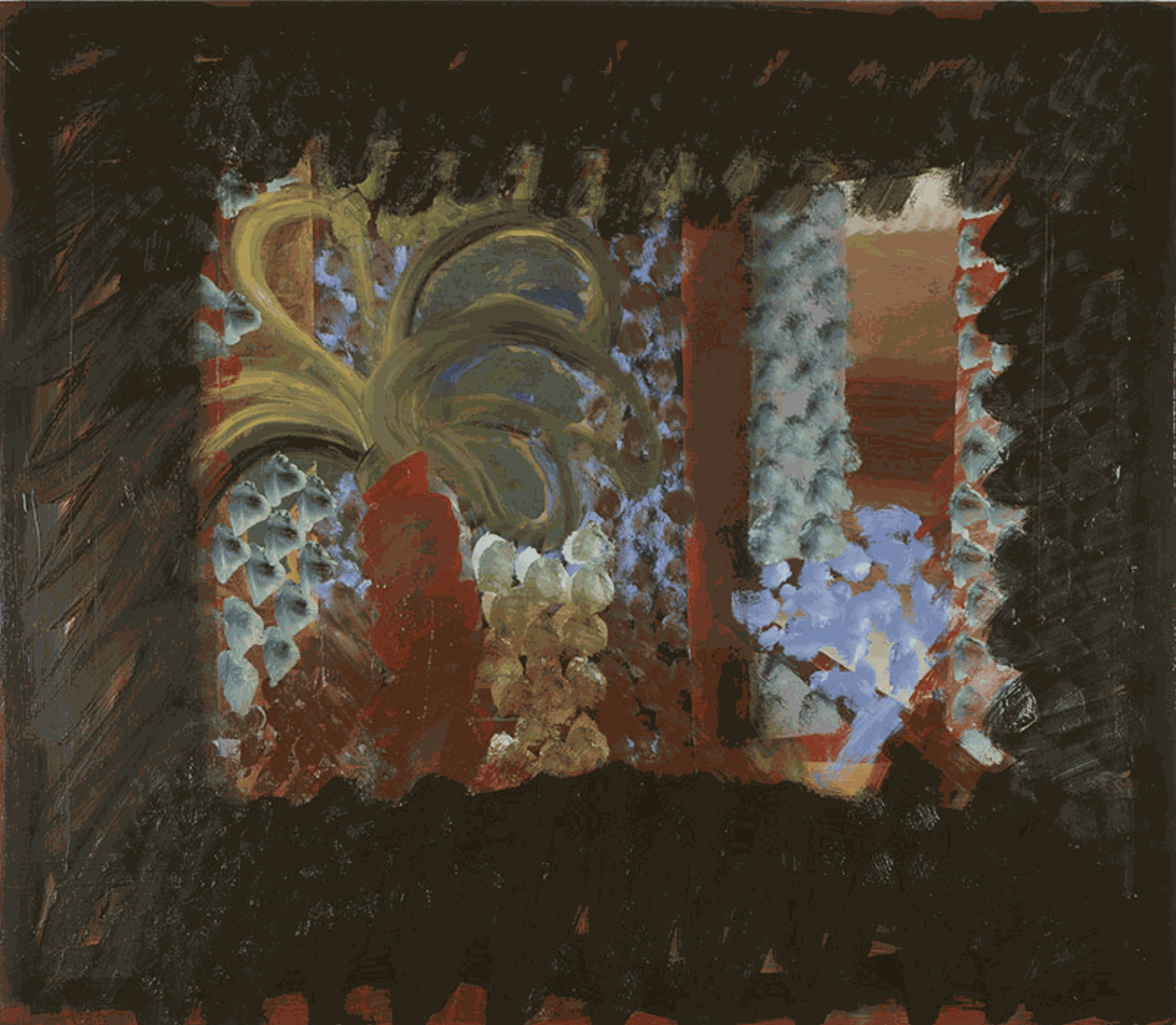

Over the course of two weeks working at one of the family’s paper mills, he made a series of twenty-seven unique works on Khadi paper. Khadi paper is a handmade product, typically of cotton, which is produced across the Indian subcontinent. Immediately after its removal from a water bath, it is dyed in pastel shades of orange, green, violet, and so on. For Hodgkin’s work, however, sheets of wet, undyed Khadi were brought to him, before the binding agent had been added, allowing him to construct images and patterns with the same vegetable dyes normally used to give the paper its distinctive monotone hue. The combination of Indian techniques and materials with Hodgkin’s personal style of mark-making is an unusually sympathetic meeting of Orient and Occident.

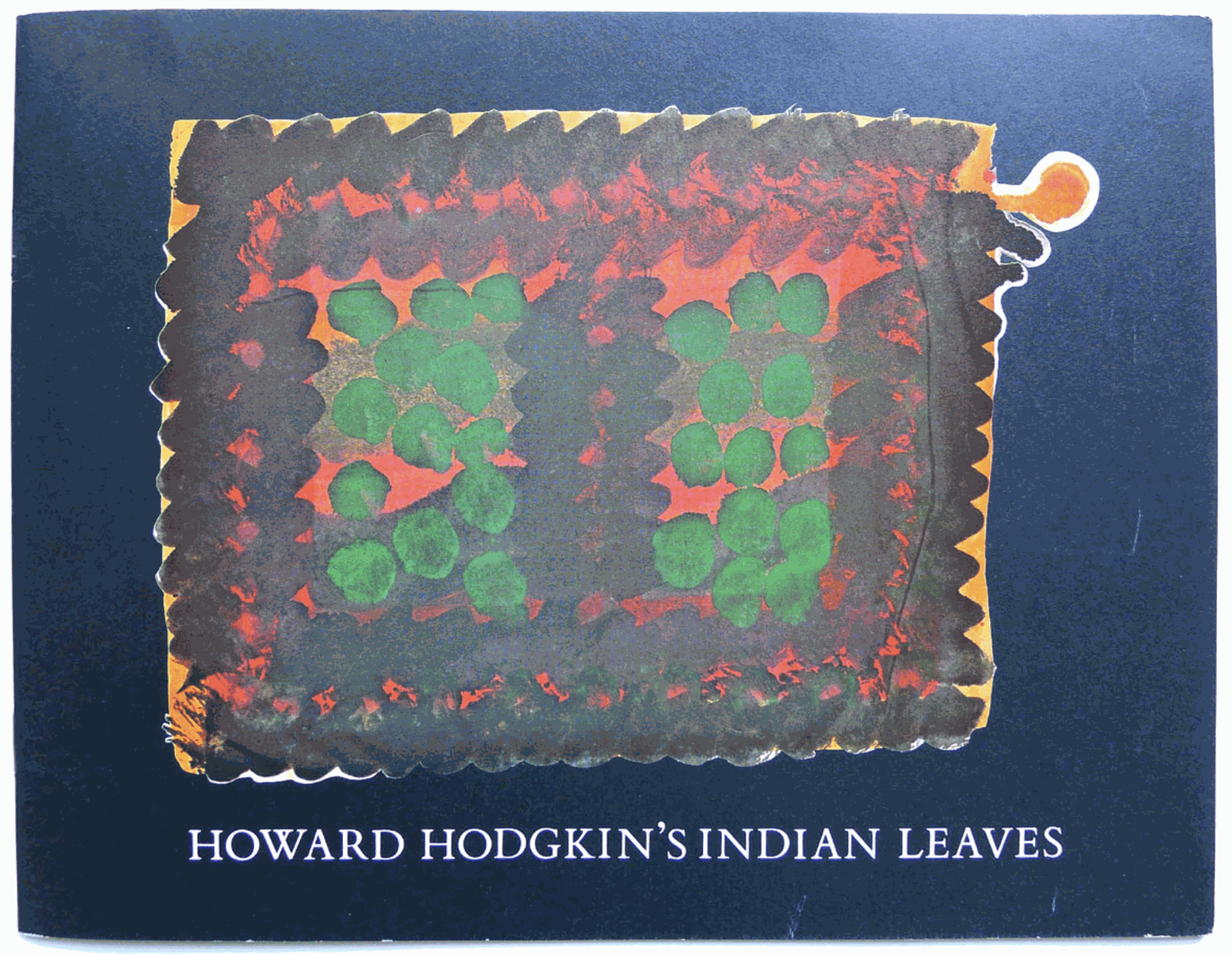

Each work in the series was subtitled ‘Indian Leaves’, as if the works were ‘leaves’ taken from a single book – a consideration which relates to the artist’s love of Indian and Persian manuscript paintings. Fifteen of the works were selected for a dedicated exhibition at the Tate Gallery in the autumn of 1982. Window (Indian Leaves) was reproduced on the cover of the accompanying catalogue, in which Hodgkin reminisced about the series.

The subject matter is very straightforward. Many of the pictures were vignettes of things I’d seen, like a concrete wall with garlands of flowers hanging from it; vistas of the sky and horizon; a train crossing the distant landscape, and so on. They are a kind of anthology of Indian images, and also a sampler of all the different kinds of language I use in my paintings, but used in an almost simplistic way.

While Hodgkin maintained his principal studio space in London, throughout his life India was a special place of retreat and restoration for Hodgkin. Writing shortly after the artist’s death, his friend Nicholas Serota recalled the day in 1973 when he first met Hodgkin.

I remember we talked that day about his love of Matisse, Bonnard and particularly about his love of India. These were the stars that guided him throughout his life and career. He first went to the India in the mid-Sixties and the people and the landscape captivated him.

The connection with India was not just a private one, though Hodgkin was loath to discuss the specific people and places behind individual paintings. The country entered into his work, an influence which prevailed over certain of his paintings with an abstract sensory power reminiscent of Proust’s madeleine moment – incoherent, unrationalised, non-verbal, and entirely felt. Another of Hodgkin’s friends, the novelist Julian Barnes, once mused about this connection between places and individual paintings.

When travelling, H.H. and I have a running joke. From time to time, sitting in a bar, looking across a piazza, relaxing in a restaurant, he will say, with a delivery poised between self-satire and true contentment, ‘I feel a picture coming on.’ […] I often wonder what is going on in his head at these moments, as he sits, chin out, eyes half-closed, preparing his future memories.

During his lifetime, Hodgkin amassed an impressive and well-known collection of Mughal art – most especially miniature paintings, 110 of which were exhibited at the Ashmolean Museum in 2012. His tastes were not restricted to Indian culture, however, and a sale of his private properties in 2018 revealed many eclectic pieces of Western art and furniture. His marble bust of King George II by Michael Rysbrack, one of the leading sculptors working in Britain in the eighteenth century, is especially curious – a refined, stone-cold counterpoint to the warm sensuality of Hodgkin’s Indian-inspired work.