In 1960, Anthony Caro crossed the Atlantic. Upon his return to Britain he began producing sculpture that was immediately recognised for its originality, resounding not just at home but capturing an audience of international supporters too.

Anthony Caro’s (1924-2013) formative experiences were eclectic. Like the former Tate director Nicholas Serota, he went to Christ’s College, Cambridge, where he took the engineering tripos in the 1940s. He was later a part-time assistant to Henry Moore between 1951 and ‘53 and, unusually for an English artist at the time, his first solo exhibition was held abroad at the Galleria del Naviglio, Milan, in 1956.

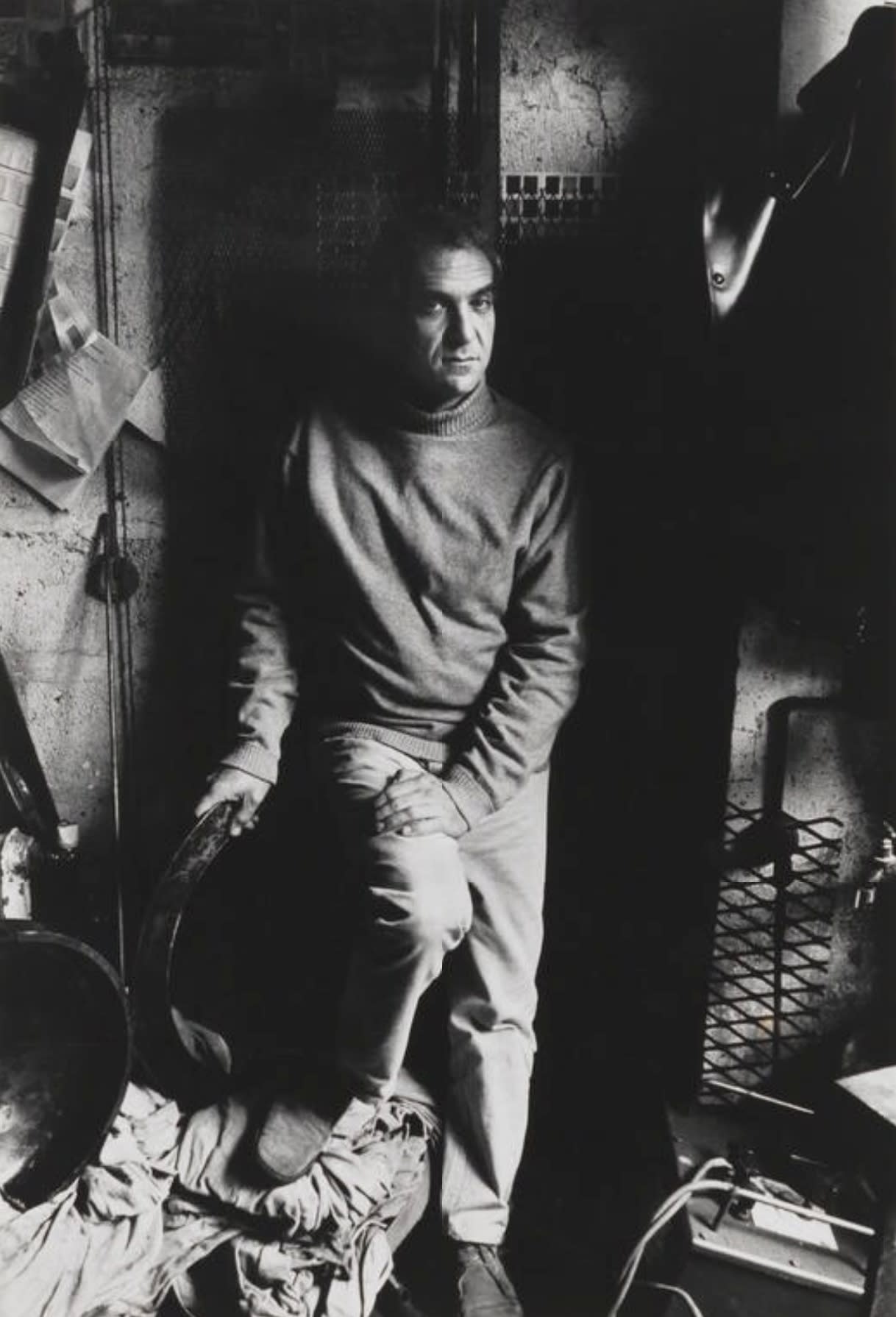

Sometime around 1960, Caro dispensed with the clay modelling used by Moore and took up welding tools. With an oxyacetylene torch, he began piecing together planes of steel and aluminium. The approach was improvisatory. Guided by the desire to escape ‘massive’ sculpture, associated with traditional figure-based sculpture, Caro’s new work of the 1960s broke apart into a fluid structure of related planes, leaving behind the plinth and breaking into the viewer’s own space. Lord Snowdon’s photograph of him, taken in 1968, suggests the transformation that had taken place: glinting fragments of metal hang about the sculptor in a darkened space, with a grille at his back and his side.

The excitement around Caro’s new abstract sculpture was considerable and his work almost immediately surpassed leading American practitioners as the standard bearer for international modernism. After William Turnbull introduced him to the eminent American critic Clement Greenberg in 1959, Caro travelled to the United States where he associated with abstract artists like Jules Olitski and Kenneth Noland. He commented later that ‘America made me see that there are no barriers and no regulations.’ As the art historian Thomas Crowe has pointed out, though it was initially the prompt from American examples which galvanised Caro, ‘Modernism in New York proved just as much in need of him’. Under siege from anti-materialist and pro-consumerist art alike, Caro’s work gave new life to the abstract cause in the culture war. Greenberg was said to be delighted when he saw photographs of the new work.

In arranging hefty lumps of scrap metal, Caro demonstrated a paradoxical degree of lightness and ease: weighty panels stand upright while heavy planks fly upwards and hang suspended in mid-air. This sculpture is not seamless, however, and each fragment is frankly joined together by welds – an accretion of liquid metal which courses along each intersection. Every style requires a technique, and in Caro’s case that technique was oxyacetylene torch welding, first originated in a fine art context by Picasso and his collaborator Julio González earlier in the twentieth century and later taken up by the American David Smith. The new high-temperature equipment made it possible not only to use metals with a higher melting point, but also to join them together in more daring ways, and this Caro did with instinctual fluency.

The title of Toward Centre sums up a formal shift in Caro’s work which began in the late 1970s. Where earlier pieces had been diffuse, with expansive structures and a mixture of planes and extended joins, his later work began to develop a centrifugal tendency. Compact clusters of steel converge on and enclose a negative central space – a stage set which configurations of welded metal variously obstruct and reveal. Unlike much earlier geometric abstract art, Toward Centre epitomises Caro’s ability to disturb the natural right angles which result from combining flat planes, instead clustering his planes of industrial metal and making them stack, lean and break apart.

Such works were meant for viewing in the round, and their diffuse structure gives them a different appearance from each angle of approach, with many elevations bearing a fleeting analogy to commonplace objects (an office desk, a piano, etc.) before transforming into sculpture once more. This observation applies just as much to a contemporaneous work like Odalisque as it does to Toward Centre. The fleeting images suggested by Caro’s sculptures give his work an enduring quality, and his reputation is destined to last well beyond the initial fanfare of modernist acclaim that he attracted in the 1960s.