Fernand Léger’s art brought together the city’s thrumming with the peculiar lives of the people who live there. An ardent socialist in later life, he used artistic invention to ennoble his proletarian subjects.

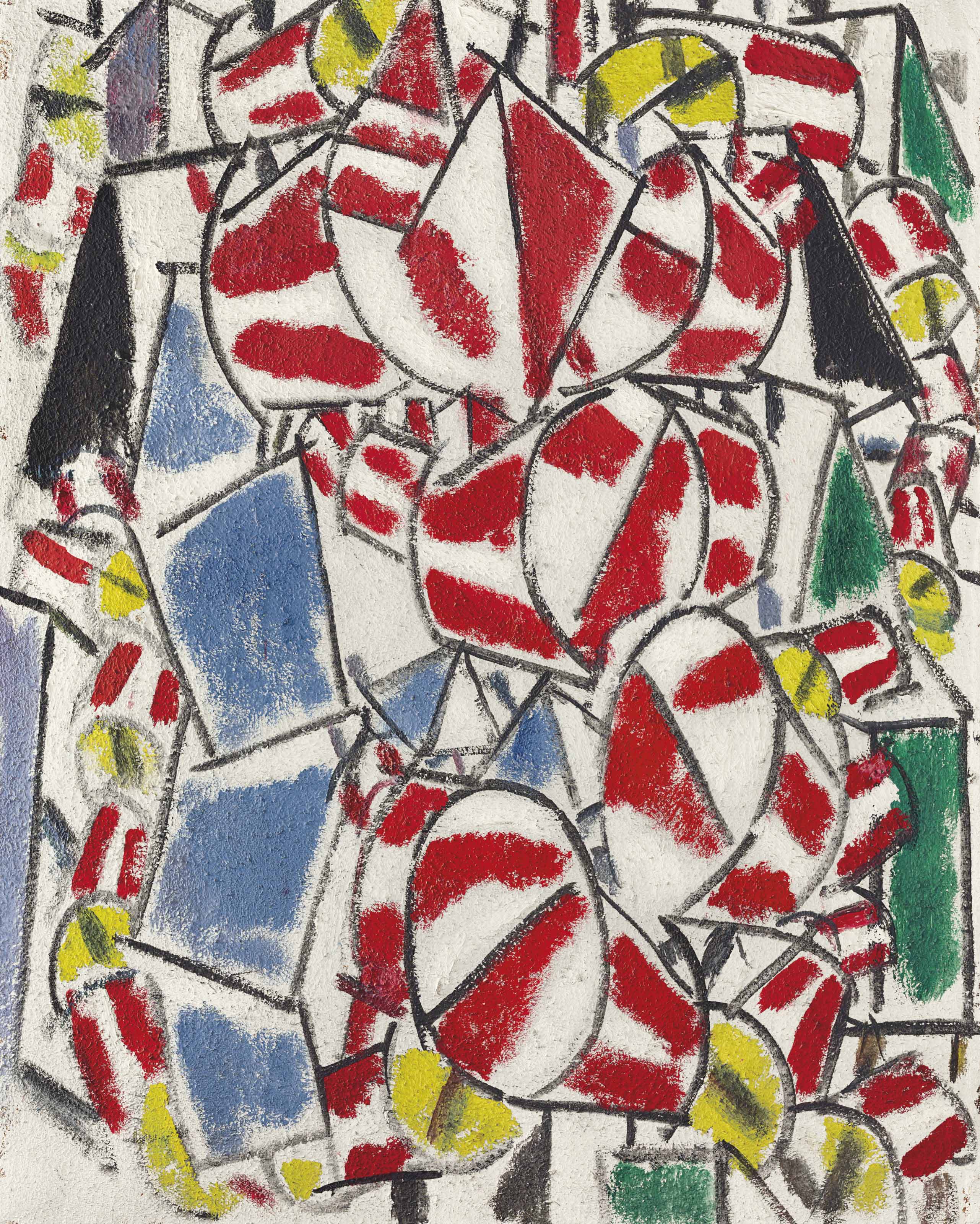

Street life was an abiding, career-long interest of Léger’s (1881-1955). Though his artistic manner migrated from mechanistic cubism to a stylishly individualised mode of social realism, the churning metropolis fed his imagination from start to finish. Though his early cubist works such as Contraste de formes show a desire to purify art and remove the human presence, it was during his service in the First World War that he came to believe in the vital importance of that human presence, as he later described.

Suddenly, and without any break, I found myself on a level with the whole of the French people; my new companions in the Engineer Corps were miners, navvies, workers in metal and wood. Among them I discovered the French people. […] The exuberance, the variety, the humour, the perfection of certain types of men with whom I found myself; […] I found them poets, inventors of everyday poetic images […].

It was these people that Léger dedicated the rest of his life to representing.

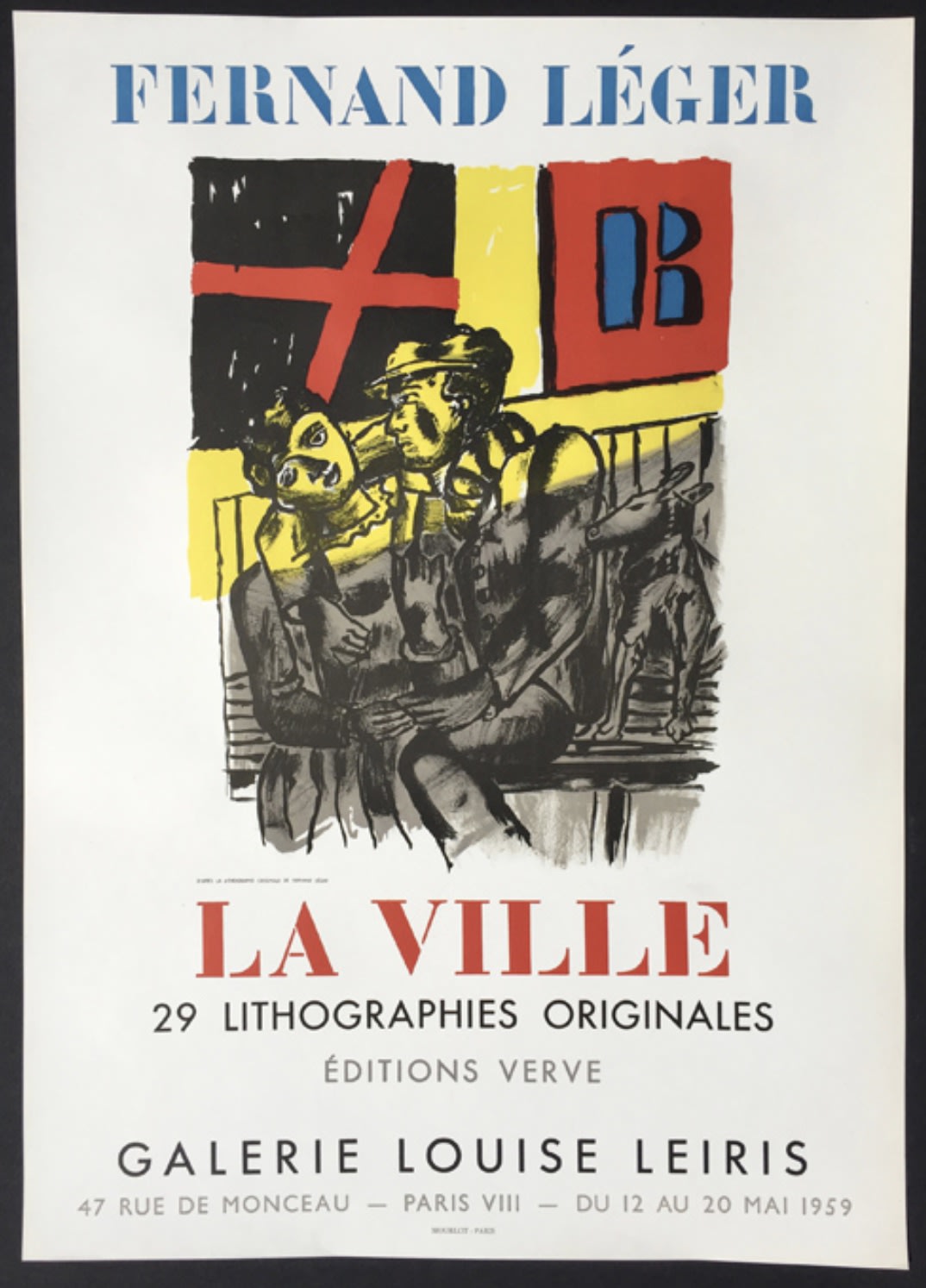

After the war, Léger rose to the upper heavens of Parisian modernism alongside Picasso, Juan Gris, Jean Metzinger and the rest, fêted for the formal clarity of his representational style. In 1935, he was given a solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and, for the duration of the Second World War, he lived in the United States – an exile forced by the suffocating spread of reactionary fascism. After the war, however, his style blossomed into a vision of proletarian paradise. Happy workers, bicycle rides and paid holidays at the beach reflect the artist’s need to make art about ‘the people’, as epitomised by a painting like The Big Parade (1954, Guggenheim Museum). The distinctive, well-fed figures of his earlier years became even more fulsome in his celebratory late work, no more so than in La Ville (‘The City’), a portfolio set of twenty-nine lithographs which weave together the architecture and people of Paris using continuous strips of dazzling colour.

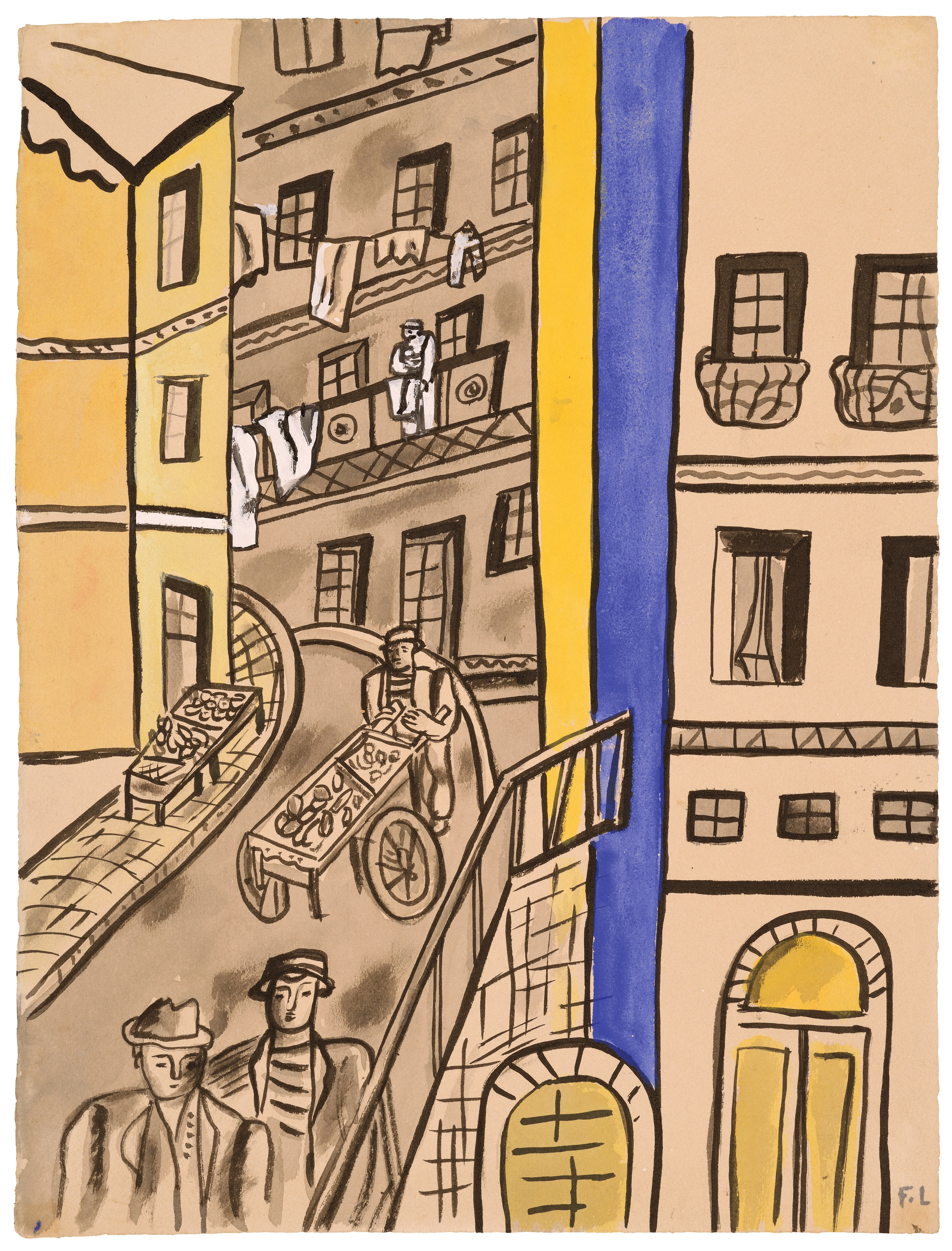

The lithographs were reproduced from watercolours and gouaches which Léger made in the last few years of his life, of which La Rue (‘The Street’) is one. The spatial treatment of the apartment blocks is characteristically inventive, a continuous plane which knits together different perspectives. This is combined with the prosaic life of Parisians: laundry is drying on washing lines strung up between apartments and a man pushes a cart along the road. In La Rue, Léger is not regarding the glamorous inner city, but rather the outer rim of suburbs inhabited by common people. The central vertical band of yellow and blue is a characteristically formal intervention, a note of high colour amidst the plaintive grey streets. Other subjects from the Ville series include the Eiffel Tower, the Opera and Montparnasse, but it is prosaic works like La Rue, Le Café and Les Amoureux which show life in Paris with the greatest sympathy.

Though Léger was able to complete the autograph works, from which the lithographs would later be made, it was only the intervention of his widow after his death which ensured the portfolio’s publication. Léger had two wives. He was unfaithfully married to Jeanne Lohy from 1919 until her death in 1950, and one of his main distractions, Nadia Khodossevitch, an erstwhile student and later teaching partner, was to become his second wife in 1952. It was Khodossevitch who worked on the production of La Ville with the Paris-based art publisher, Georges Tériade, and who later oversaw construction of the Léger Museum at Biot which opened in 1960. As Léger’s executor, she was also involved with the exhibition of La Ville at Galerie Louise Leiris in 1959, which coincided with the portfolio’s publication. An inscription on the reverse of La Rue – ‘coll. H.X.’ – shows that it was in Nadia’s collection after Léger’s death (her initials are signed in Cyrillic script).

It is an enduring cliché of European modernism that stylistic progress is driven forward by ingeniously talented individuals, and it is artists like Léger which have sustained it. Considerable attention has been given in recent years to his success as a polymath, producing murals, book illustration, ceramics and film. However, his success in these media derived from his talent for making paintings and watercolours: ingenious works of art which interlock their subject with terse formal devices. It is works like La Rue which exemplify the meeting of these two halves, encapsulating Léger’s joyful exploration of composition and colour, the human body and complex human society.