A masterly scholar and a painter of light, John Golding was a man of divergent talents, beginning his exhibiting career at the same gallery as Bridget Riley and providing a nuanced historical account of abstraction in his Mellon lectures later in life.

Golding (1929–2012) first came to prominence as an academic at the Courtauld Institute of Art, where Anthony Blunt arranged for his doctoral thesis to be supervised by Douglas Cooper. The subject was cubism, and the relationship between supervisor and supervisee was later described by Cooper’s partner at the time, John Richardson.

At his worst, [Cooper] was academically nit-picking, bitchy and vindictive, especially so to his former Courtauld pupil, the scholar/painter John Golding, whose definitive study of cubism Douglas had enthusiastically encouraged until he realised that the apprentice was writing the masterpiece that the sorcerer had failed to do. Douglas’s attacks on the book did Golding nothing but good and the perpetrator nothing but harm.

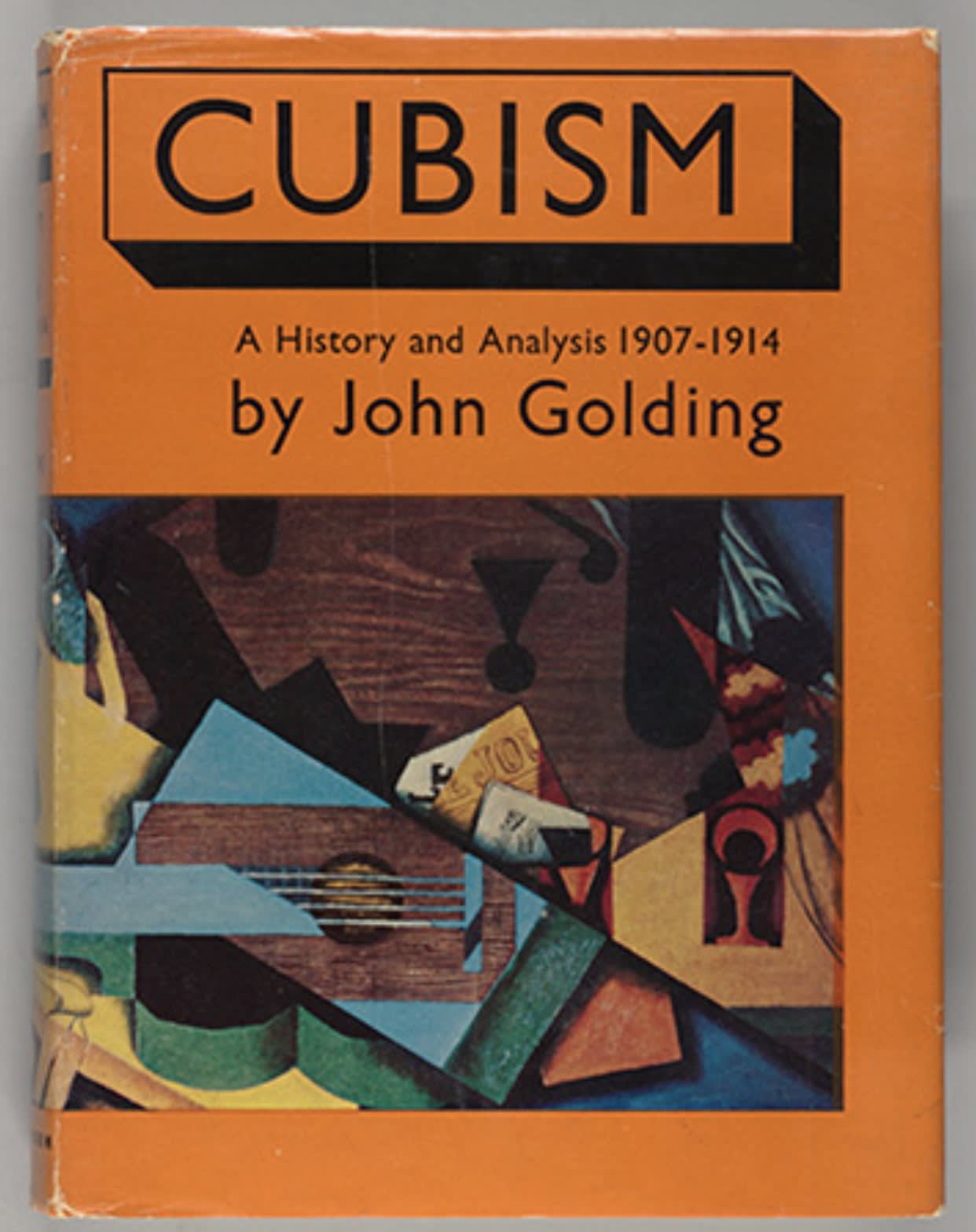

Golding’s thesis was later worked up and published by Faber in 1957 as the definitive scholarly monograph on its subject. It was this tome on which rested Golding’s professional status as a scholar, accounting for subsequent accolades including the Slade Professorship at Cambridge among others.

A five-minute walk away from the Courtauld Institute, then based at Portman Square, and a world apart in spirit, was Gallery One. It was founded by Victor Musgrave in 1953 and was eventually based at 16 North Audley Street after starting up in Soho. The gallery displayed an eclectic range of contemporary art reflective of what was being made in London in the 1950s and ‘60s, as well as showing work by artists of European and South Asian origin like Yves Klein and F.N. Souza. It is perhaps best known for giving Bridget Riley her first solo exhibition. Golding had his turn there in 1962.

The Gallery One show was his first solo exhibition in London, having previously held two solo exhibitions in Mexico, where he grew up. His output at that time shows an awareness and appreciation of Francis Bacon, and works like Cliff Dwellers are rich with painterly incidents taking place against a pulsating black void. Being shown at such an auspicious gallery was testament to Golding’s seriousness as a painter, and throughout his life he felt the tension between his academic prestige, founded on his cubism book, and his practical aspirations as a painter which he regarded as a higher claim. In 1981 the balance shifted, leaving his position as a reader at the Courtauld to become senior tutor in the painting school at the Royal College of Art. When giving a description of himself for the A.W. Mellon lectures, which he delivered in Washington, D.C., in 1997, he described himself simply as ‘painter’.

As David Anfam has recalled, Golding rarely discussed his interests as a painter with students or colleagues and many were unaware of this part of his life. All the same, his development as an artist was loaded with art historical awareness. His creative goal of finding a ‘path to the absolute’ was the subject of his Mellon lectures, in which he argued that abstractionism emerged from a profound struggle to achieve meaning in art, whether through the mysticism of Kandinsky or the Jungian basis of Jackson Pollock’s ‘action’ painting. In works like G III (Y.B.), Golding responded to the American genre of colour field art, bringing together areas of saturated colour in an organic, mural-like format.

Golding's preparatory process offers an insight into such richly colourful, large-scale works. He created many delicate pastels which explore combinations and spatial arrangements of colour. In these works, some of which were filled on both sides, the paper was saturated with sensitively contrasted and intermingled channels of ochre, sky blue and sand yellow. Light was the subject of his investigations and Golding drew unfailing inspiration from the challenge of suggesting it in his work. The fluency of pastels like Drawing 80/10 was neither glib nor facile, originating as it did from an underlying process and the overarching ambition to explore effects of light – the way it transforms colour, dissolves substance, assumes its own physical presence, and so on.

This particular pastel was acquired by the painter R.B. Kitaj and subsequently donated to the Museum of Modern Art, New York, at the suggestion of their mutual friend, the critic and philosopher Richard Wollheim. (Golding is perhaps the only artist represented in MoMA’s collection who has also curated a large-scale exhibition at the museum, namely the Matisse Picasso show of 2002/03.) Kitaj wrote to Golding in February 1981 shortly after getting the work.

I am writing to tell you how excited we are to have your pastel here. Sandra's reaction was immediate delight which surprised me because we are shy virgins with abstraction. It is my first abstraction (to live with I mean), except for that small, one-off, early Hockney. I am tasting it with great pleasure and it will lead me somewhere... and it is from the life of your mind which is very important for me.

A few years earlier in 1975, Kitaj had painted a double portrait of Golding and his partner, the historian James Joll. It was called From London (James Joll and John Golding) and alongside Kitaj’s other portrait subjects, Sandy Wilson, David Hockney and E.H. Gombrich among them, the painting reflects Golding's position as one of the pre-eminent cultural figures in post-war London.