In late summer of 1903, Gwen John moved from Britain to France. Arriving by steamer in Bordeaux, she walked up the Garonne Valley as far as Toulouse, sleeping in fields and drawing portraits to make money, before eventually settling in Paris.

John (1876-1939) holds a unique place in the history of early twentieth-century British art. Like Walter Sickert and a handful of other artists, she was a bridge between advanced painting in Britain and France, living in Paris from 1903 while exhibiting a little in London. (She lived in the Montparnasse district until 1913, and thereafter lived in the suburb of Meudon until her death.) Unlike Sickert and the ‘Bloomsbury’ artists, however, John thrived on solitude and religion. In her mature work she achieved a raw sense of tenderness and vulnerability, communicated at once through a delicate range of tonality (rarely deviating much beyond ochre brown and ash grey) and the disarmingly natural depiction of female figures in a state of repose.

Despite her personal achievements as an artist, her reputation has been complicated by her relation to the period’s leading men of culture (principally her brother Augustus John, her erstwhile lover Auguste Rodin, and the American collector John Quinn). These relations do little to illuminate her work, though they are highly relevant to a history of fin-de-siècle British-French cultural networks. For instance, John modelled for Rodin’s maquette of Muse nue, bras coupé – a work commissioned as a memorial to Whistler, who she had briefly studied under in 1898-99. Adapted from the Venus de Milo, the maquette provocatively opens the woman’s legs to provide what Rodin later described as a ‘quivering thrill of generous nature’. John’s implication in such an avant-garde network is of great biographical interest, but as her later accomplishments suggest, her relationship with Rodin from 1904 was in fact a period of stifled creative ambition.

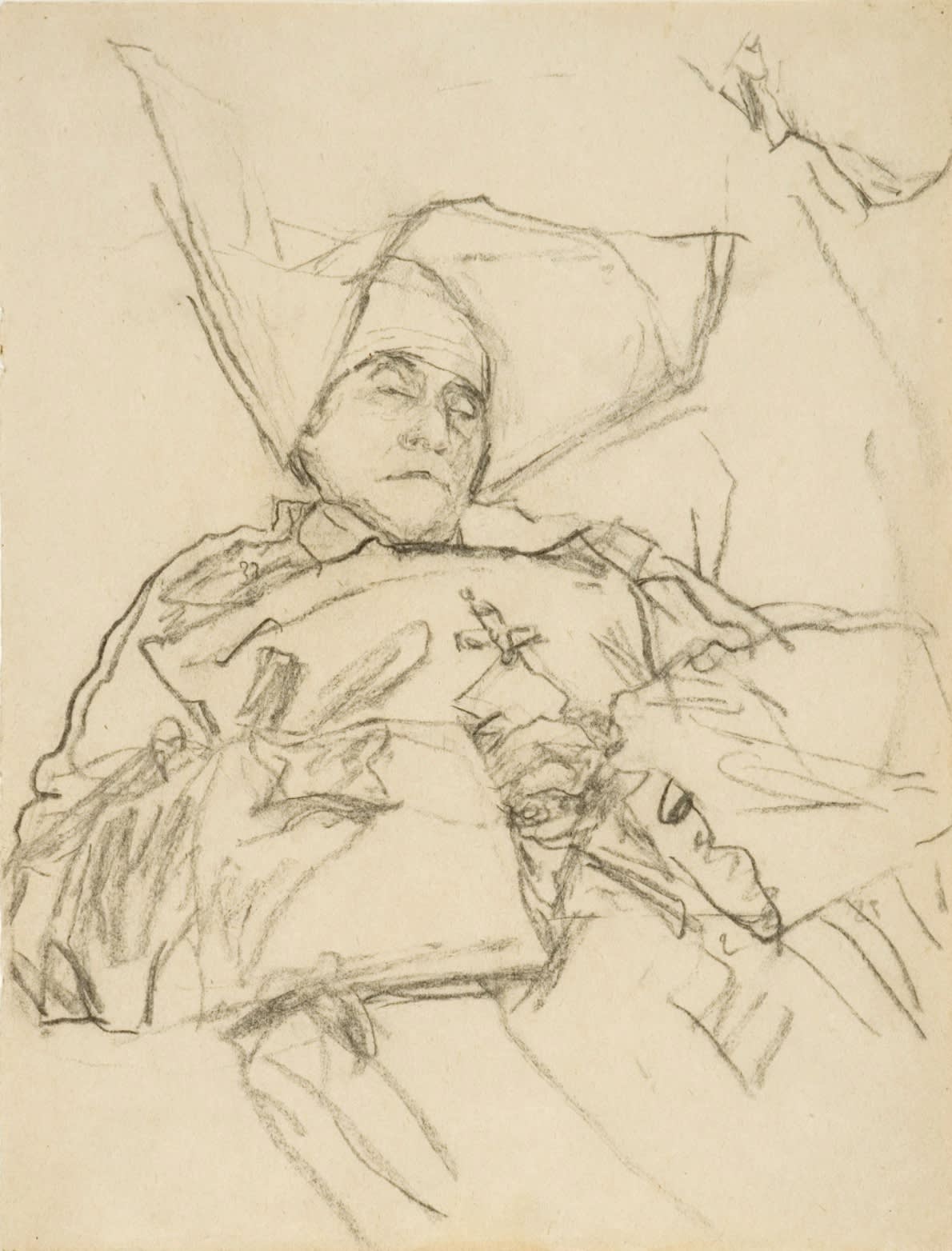

What followed her devotion to Rodin was a period of productive independence, including her conversion to Roman Catholicism in 1913 and a considerable refinement of her technique and the quality of her work. Her mature paintings have an encrusted surface of dry impasto, often stippled or detailed with subtle painterly texture, while her works on paper used immaculately precise pencil outlines and washes of delicately graded tone in watercolour and gouache. In Sleeping Nun, the recumbent figure is swathed in the Dominican habit: a pale tunic, a black scapula, and the pastel folds of a cornette headpiece. The colours of each are graded to fit a calculatedly narrow tonal range which defines John’s work. The continuous pencil outlines, especially around the cornette and the shoulders, demonstrate a heightened degree of control and a considerable technical facility.

After her confirmation into the Roman Catholic Church, the defining subjects in her work became nuns and women in prayer, and her work was defined by the combination of tonal pallor and devotional sincerity apparent in Sleeping Nun. Not content to simply ‘make a picture’, John pursued this subject repeatedly and other versions of Sleeping Nun (or The Dying Nun) exist in the National Museum of Wales and the Scottish National Gallery. Similarly, between 1915 and 1921, another recurring subject was Mère Poussepin – a long-dead nun of the seventeenth century that founded the Dominican Sisters of Charity at Meudon. John painted her seven times. This sustained exploration of the same pious women, whether living, dead, or dying, suggests a meditative focus in John’s work which is analogous to the repeating offices of prayer so central to the Catholic faith.

Despite the prevailing theme of meditative tonality, since her death Gwen John’s work has been presented in a wide variety of contexts. In 1940, she was included in a group exhibition at the National Gallery in London, British Painting Since Whistler, alongside Henry Tonks, Mark Gertler, Paul Nash and Graham Sutherland. In 1987, for the momentous Royal Academy exhibition British Art in the 20th Century, she was grouped with late Sickert and Euston Road School painters. More recently, she was presented alongside her brother at Tate Britain in 2004 – a more obvious choice, despite their artistic disparities.

At the same venue in March this year, a Spotlight display of her work opened to the public. It offered a minimal biography, with almost no references to Whistler, Rodin or Augustus, and though these important figures cannot be removed from her life story, the small exhibition at Tate provides a refreshing change from some of the more haphazard comparisons used by curators since her death. It shows what any solo exhibition of Gwen John’s work will always show: her original accomplishments as a painter.