In 1964, William Crozier appeared in a remarkable Arts Council exhibition of ‘Six Young Painters’. Amidst work by Peter Blake, David Hockney and Bridget Riley, however, Crozier struck a contrastingly serious note. To him, it was a ‘shabby and meretricious decade’, and in his own work of the period he assumed a far-sighted, humanistic approach.

For a time in the late 1950s and early 1960s, Crozier was a flâneur of Soho. He was well acquainted with the art world celebrities of his day, Francis Bacon included among them, though he tended to shun the egotistical outlets for self-promotion which many artists had started to exploit. His work of the period was more indebted to the serious, introvert, quietly Francophile art of painters like MacBryde and Colquhoun – his fellow Scotsmen known as ‘the two Roberts’. Moreover, like another Scots-Irish painter in London, his friend William Scott, he was interested in the fragile relationship between abstraction and representation.

By the 1960s, after periods working from the marshlands of Essex and the rugged terrain of Andalucía, Crozier had developed a personally distinctive style of landscape art which grew in part from the desolate environments which attracted him. Despite undertaking a period of psychoanalysis in the late 1960s, the greater size of his canvases from the period suggests a growing ambition and confidence in his work. Far from reducing his creative powers, the traumatic events of 1969 – his visit to Bergen-Belsen and the outbreak of the Troubles in Northern Ireland – appear to have provided a spur to Crozier. Some of his paintings from this time were displayed in Edinburgh at Richard Demarco Gallery, and the combination of bare white walls and lowering, effervescent clouds of paint must have been a striking experience for those attending the 1969 Edinburgh Fringe.

The year before Crozier painted Black Lake, he was appointed as Head of Fine Art at Winchester School of Art, where his ambition was to establish a school of painting based on the European tradition. There he employed the Scottish artist, John Bellany, who had recently graduated from the Royal College of Art. Bellany’s work of that period echoes the free brushwork and vibrant colouring which distinguished Crozier’s output at the time, and both artists are notable for their visits to Nazi concentration camps and concerns about the fallibility of the human condition.

Crozier’s landscape art was perennially inspired by an obsession for particular places. His series Swift’s Lake, for example, made in 1977 and ‘78, was inspired by the water meadows which lie immediately to the north of Winchester School of Art. Around that time, he explained to his fellow artist Ian Kirkwood that the mark of success in a landscape painting was sometimes that one had ‘extracted the very essence of the thing that is there [in a place]’. It would be unusual if Black Lake was not based on a specific place, and there is an elementary topography to the painting’s composition which suggests a certain land, possibly the same watery site in Winchester: a camouflage foreground of red and green, the unmanaged lakeside growth perfect for Elephant Hawk-moths; the ink-like waters of the lake, snaking flatly through the middle of the picture; and the suggestion of a horizon, partially concealed by a verdant cloud-like canopy which bears only a casual relationship to the tree trunk positioned at centre-left.

Although the experience of a particular site was always the starting point for Crozier’s landscapes, his purpose was much more ambitious than simply capturing the spirit of place. In fact, he did not believe such a thing existed. As he explained, ‘[l]andscape is not the subject; it is the vehicle through which I can express intangible things. Things which have no narrative. Loss, memory – all can be done through the language of landscape’. In Black Lake, the marriage of place with Crozier’s sumptuous, saturated washes of colour and the heightened drama of the composition creates a tension between the sensuality of paint and the struggle for the image.

1. William Crozier, Black Lake, 1969, oil on canvas, 152 x 152 cm

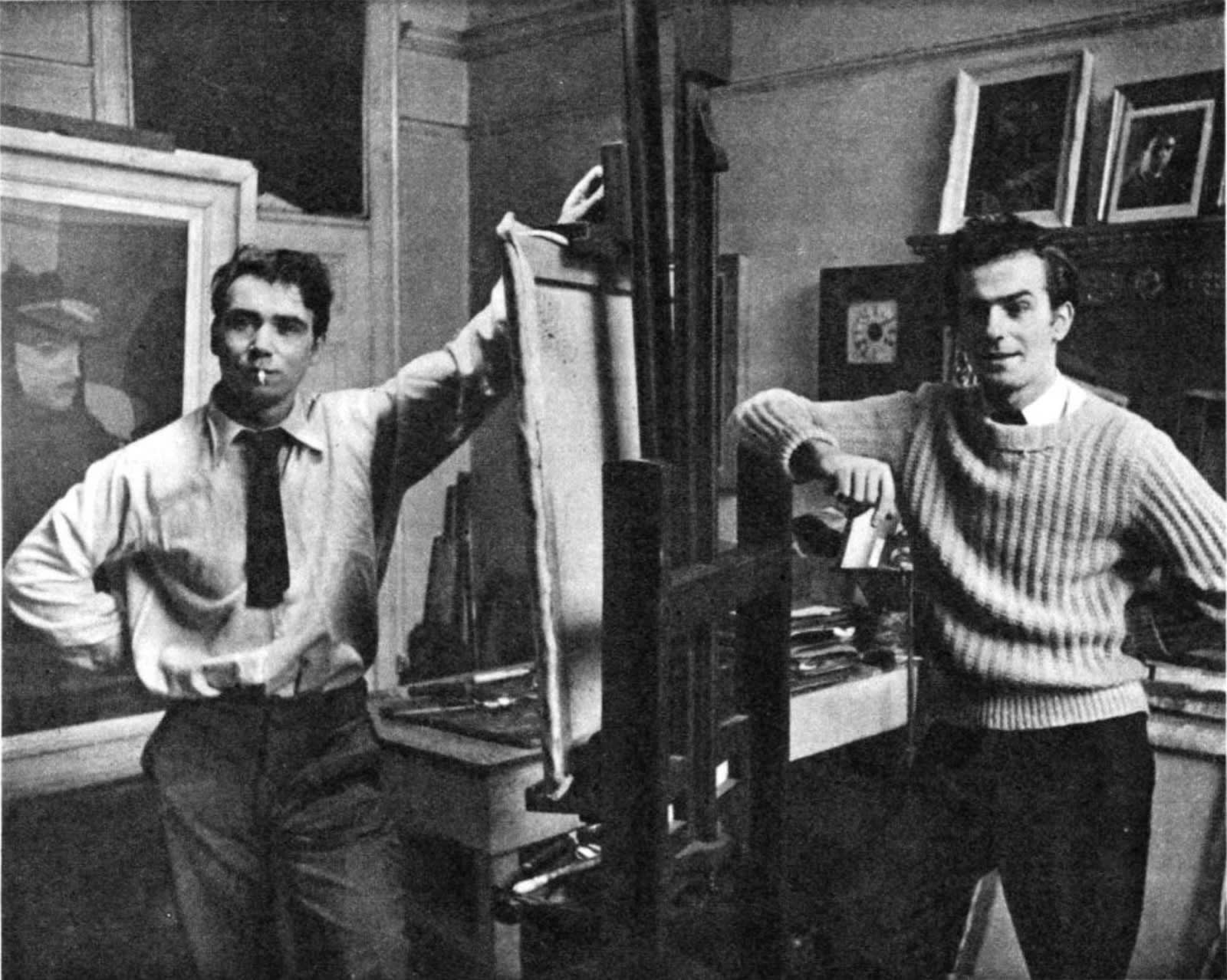

2. Robert MacBryde and Robert Colquhoun in Picture Post, 12 March 1949

3. Douglas Hall and Sally Holman at William Crozier's 1969 exhibition at Richard Demarco Gallery, Edinburgh

4. William Crozier, Swift's Lake, 1977-78, Private Collection

5. Black Lake (detail)

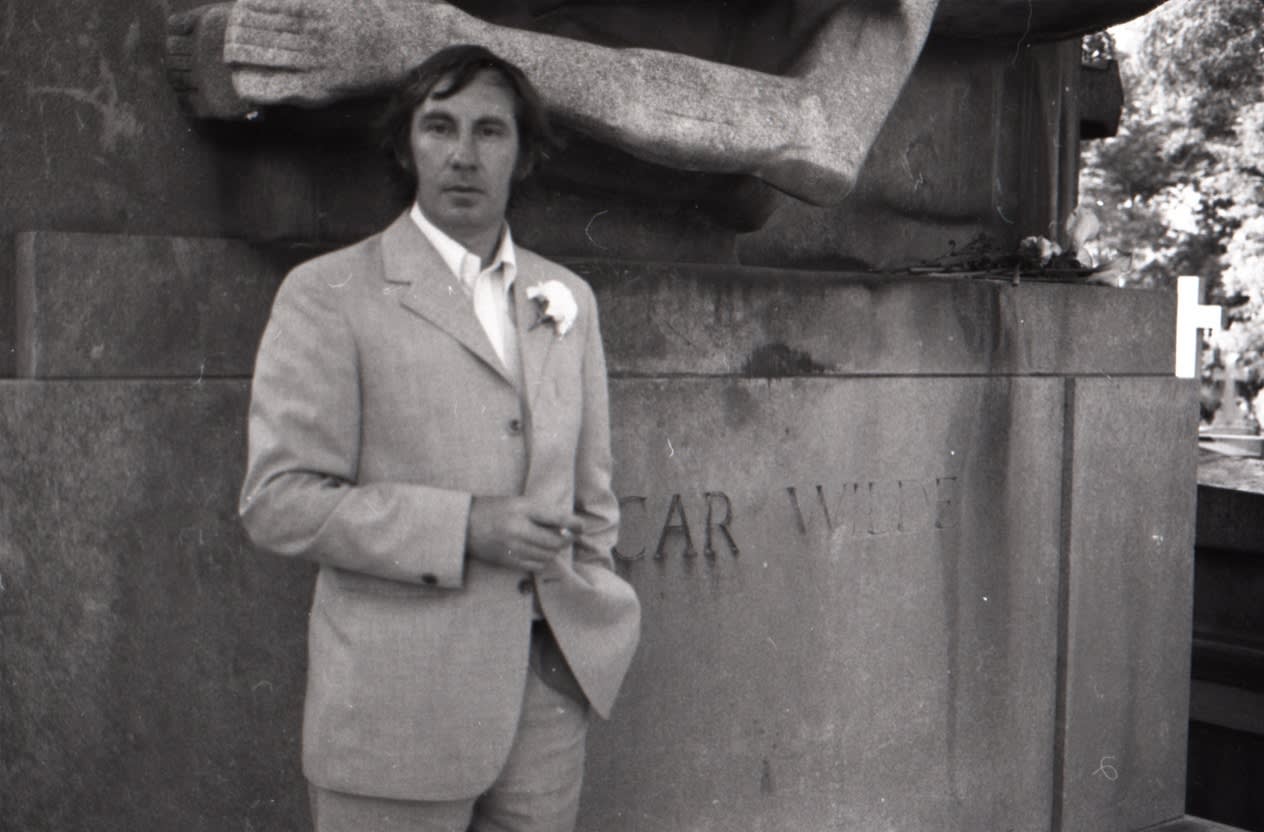

6. William Crozier in Paris © The Estate of William Crozier