Paul Nash’s reputation as one of Britain’s great landscape artists is well-known. Less well known are his photographs, an artistic achievement in their own right, which he started taking in 1931 after his wife had gifted him a Kodak camera.

Nash (1889-1946) was one of the key organisers of British modernist culture and played a leading role in the establishment of Unit One. He was also one of his generation’s subtlest interlocutors between culture and landscape, and his statement in the Unit One publication (1934) shows a desire to synthesise modernism with the traditions of English landscape art.

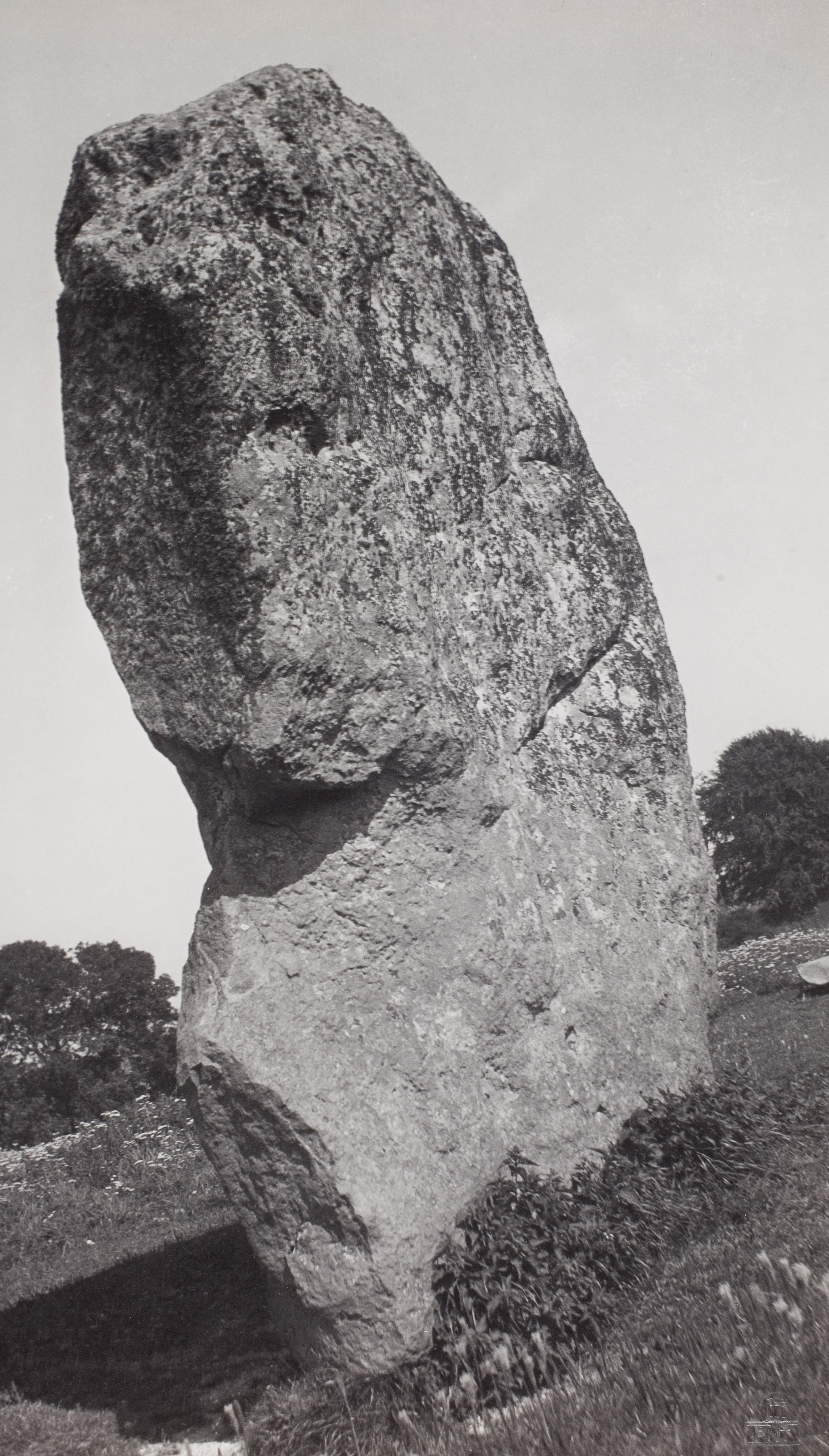

Last summer, I walked in a field near Avebury where two rough monoliths stand up, sixteen feet high, miraculously patterned with black and orange lichen, remnants of the avenue of stones which led to the Great Circle. A mile away, a green pyramid casts a gigantic shadow. In the hedge, at hand, the white trumpet of convolvulus turns from its spiral stem, following the sun. In my art I would solve such an equation.

Working in the time immediately before the massification of heritage tourism, Nash was alert to the undiscovered or fugitive aspects of the English landscape. He perceived Avebury, for example, as a human monument that has a symbiotic relationship with nature: the lichens and the ‘green pyramid’ enfold this cultural artefact in a world of beautiful but artless patterns and asymmetry.

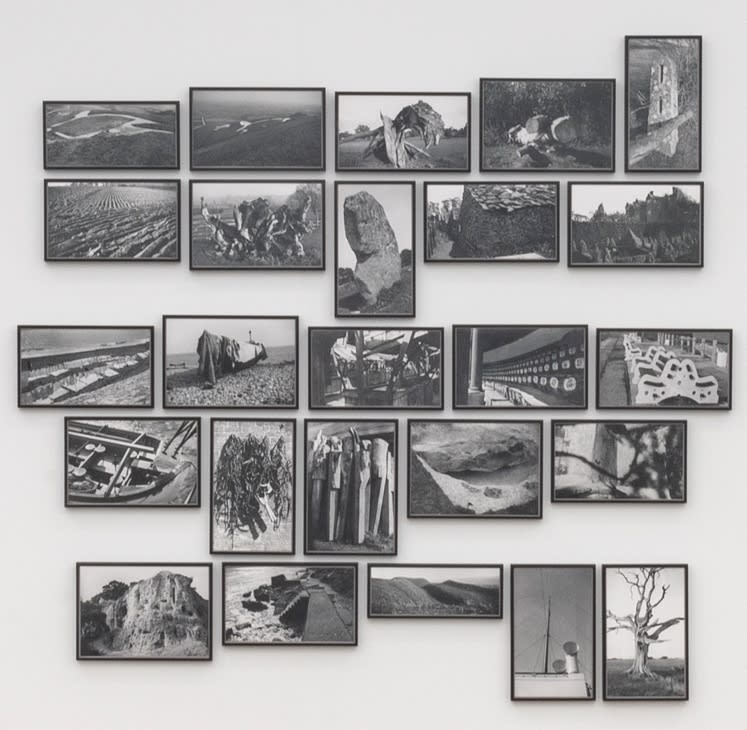

In 1978, Fischer Fine Art presented an exhibition dedicated to Nash’s photographs. An artist of wide-ranging talents which included easel painting and textile design, the display drew public attention to his work with the camera. A few years earlier in 1970, Nash’s executors had deposited a large tranche of his negatives – over 1,200 of them – with the Tate Gallery Archive. (Today, contact prints of these negatives can be browsed in the Tate Archive reading room. They are stashed in a succession of folders which are kept on a shelf in the corner.)

It was from the negatives in the Tate Archive that Nash’s contemporary, the artist John Piper, selected twenty-five photographs to be printed by Fischer. The set was called A Private World and was made in an edition of forty-five, with six additional sets numbered from A to F (three for the Nash executors, one for the Tate Gallery Archive, one for John Piper, and one for Fischer). Himself a distinguished landscape artist and an accomplished photographer, Piper argued for the quality and professionalism of Nash’s photographs. In the introduction to the Fischer catalogue, he wrote:

If [Nash] wanted to take something and the sun was not out, he would wait for it; if he wanted to shadow a certain angle, he would wait for it. He would stalk the Uffington White Horse or Maiden Castle or the stones at Avebury until the place and the light were right and his friends who drove him would have to wait and stalk too.

(Unlike Piper, who owned a car and drove all around the country, visiting Ravilious in Wales before the war and making occasional sojourns down to the Kent coast, Nash was asthmatic, suffering from ill-health throughout his life, and was unable to drive himself.)

After the outbreak of war in 1939, Nash and his wife Margaret moved to Oxford. From there he ventured out to visit nearby country houses, including the manors at Ascot and Garsington, taking photographs all the while. It was sometime in 1940 or 1941 when he visited Beckley Park, a Tudor brick hunting lodge near the wetlands of Otmoor. The architectural historian Mark Girouard has described the house as ‘the most memorable of all Elizabethan lodges’, further noting that its water garden may have been adapted from the moat of an earlier medieval building. The elaborate box topiary at the house, briefly featured at the beginning of Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, was a source of special interest to Nash and was the subject of a photograph selected by Piper for inclusion in A Private World. One of the topiary shapes in the border harks back to the ‘green pyramid’ which Nash had described a few years earlier at Avebury.

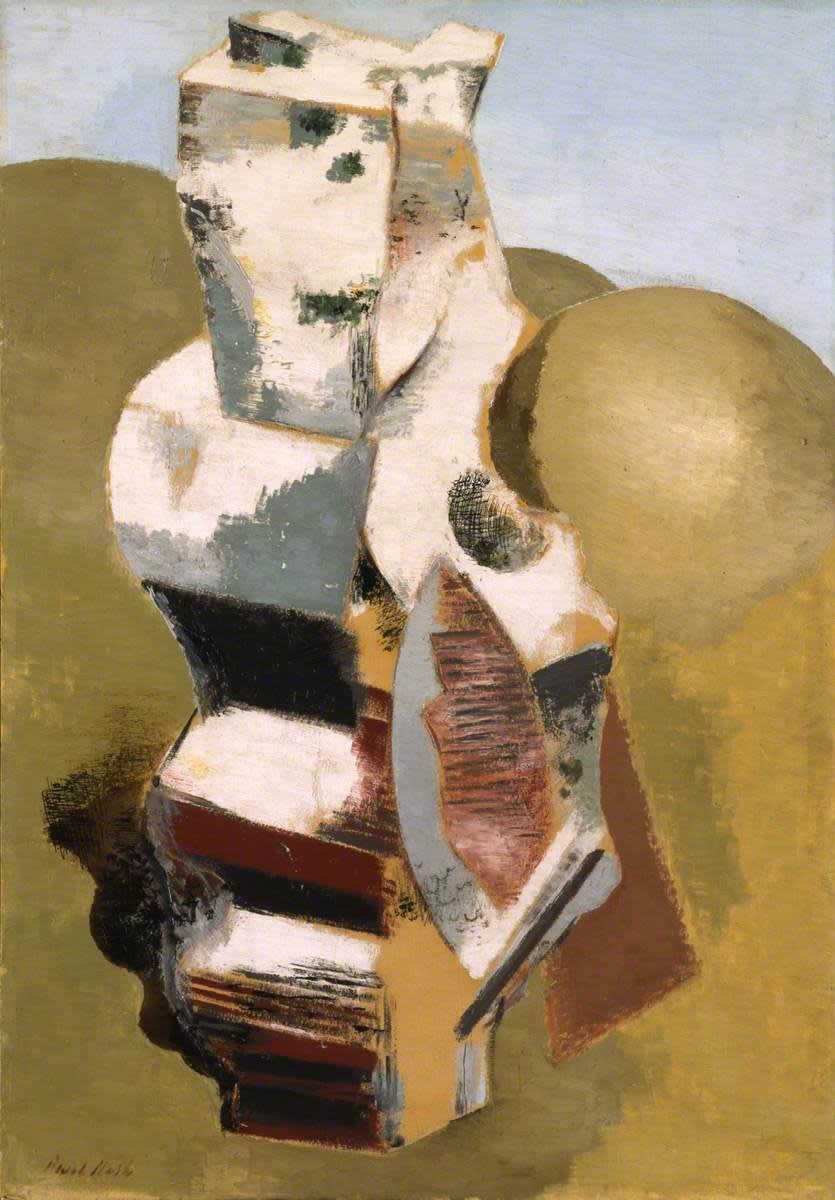

Many of Nash’s photographs have a pictorial sophistication of their own, stemming from the composition of shadows as Piper said, a richness of texture achieved in close-up, or an unexpectedly foreshortened framing of the subject. Nevertheless, as his health began to fail him, his photographs came to be an invaluable stock of imagery for his watercolours and oil paintings.

A painting like Druid Landscape, for example, was only possible with the aid of photographs which Nash had taken at Avebury earlier in the 1930s. Fulfilling this important role in his practice as they did, it is perhaps unsurprising that it took until the Fischer Fine Art exhibition in 1978 for some of the photographs to be printed, and for them to receive the kind of critical attention which this imaginative corpus of work so justly deserves.