Today, William Scott is widely known as a semi-abstract painter with Cornish connections. In the early 1950s, however, his artistic reputation was far from secure and his rise to prominence was marked by many changes of identity.

At that time, he was variously presented as an isolationist neo-Romantic, a participant in American abstraction, and even an erstwhile artistic companion of Francis Bacon who, like Scott, had Irish origins. Table Still Life also hints to his interest in Picasso, who had painted a jaunty-handled saucepan several years earlier in 1945. At a Hanover Gallery exhibition held in summer 1955, Scott’s work was presented alongside that of Bacon and Graham Sutherland – an unexpected combination which summarised the various byways running between real-life subjects and allusive, semi-abstract ways of painting in British art of the period.

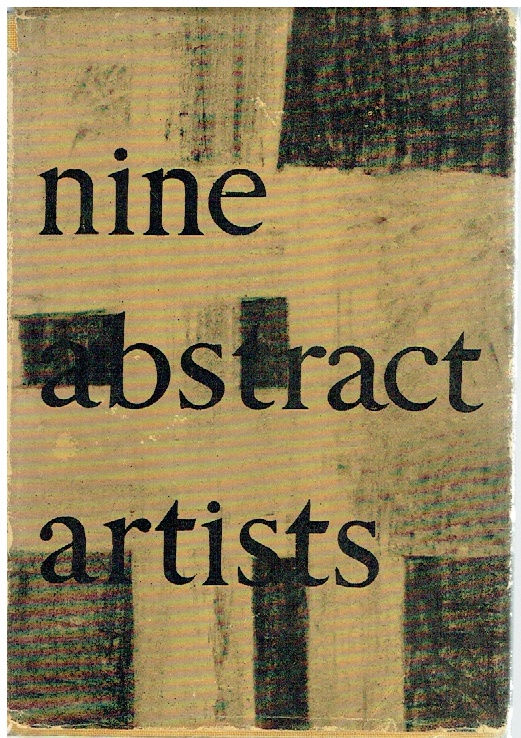

In 1954, a year before the Hanover Gallery exhibition, Scott was included in Nine Abstract Artists. This short publication was introduced by the critic Lawrence Alloway and included the work of Victor Pasmore and Adrian Heath among others. Alloway wrote that “Scott's paintings are the only ones in this book abstracted from the human figure or still-life and in most cases the process is pushed to a point of near-concretion.” This pertinent phrase, “near-concretion”, suggests the literal material qualities which Scott was achieving in his paint surfaces at the time.

In a work like Still Life on Black Table (II), painted two years later in 1956, the texture of each object was carefully variegated. Five bowl-like vessels are lined-up on the eponymous black table. Each is a different colour and a different texture: the rich, cream-like impasto used to evoke the black and midnight-blue vessels, smoothed by palette knife rather than the brush, contrast with the thin, scrubbed surfaces of the two grey vessels. While keeping the composition largely the same as the preceding version (a work of the same date and now in the collection of the Pier Arts Centre, Stromness), in this second version Scott sought to avoid the suggestion of outlines or volumetric shape. Rather, the vessels became literal accretions of paint – their texture in the work no longer pertaining to the qualities of an external object.

Like other painters of his generation, Scott thrived on the ambiguity between abstraction and representation. In 1955, he wrote a statement for inclusion in the catalogue of The New Decade: 22 European painters and sculptors – an exhibition which toured the US, starting at the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

My problem was to reduce the immediacy of the individual object and to make a synthesis of “objects and space” so that the new conception would be the expression of one thing and not any longer a collection of loosely related objects. While working towards this end my paintings contain greater or lesser degrees of statement of visual fact. Sometimes the object disappears and takes on a new meaning.

This rare statement of intention explains the role of abstraction in Scott’s work. In simple terms, he was more concerned about making a painting than he was about the still-life objects which helped him do it. Elsewhere in his statement, he referred to his frustration with earlier forms of still-life painting, where the objects represented in a picture had a symbolic value which was separate from the painting itself. Scott’s ambition was to make an artwork whose integrity came from its wholeness. To do this, his solution was to paint the table and the ground with an intensity equal to that of the pots and pans.

For Scott, the resulting sense of flatness was incidental. His practice was to paint from memory, and in consequence many of his still lifes have an elusive sense of poignance. This poignance is effectively combined in his work with an appealing material quality. Though a work like Brown Still Life possesses the intensity of something remembered, it also has less psychic, more palpable qualities. Scott’s distinctive, spindly-handled frying pan speaks of the kitchen – of onion skins and mud-flecked potatoes. Though it is difficult to summarise in words, the appearance of Scott’s still-life paintings from the mid-1950s was highly individual and represented a significant contribution to his favoured genre – no longer an academic game of placing your fruit appealingly, but a raw exercise in formal painting.