In this second focus on the art of Bloomsbury, Vanessa Bell travels to Dorset – to an idyllic village rectory, converted after the Second World War into a highly civilised bachelor retreat.

Vanessa Bell

Flowers in a Vase, Long Crichel House, c. 1951

Long Crichel House is not to be confused with Crichel House – a grand country pile nearby, set within an estate and worthy of its own television costume drama. By contrast, Long Crichel House is an old Georgian rectory, mostly constructed in 1786, which stands adjacent to the village church. A number of headstones in the neighbouring churchyard are just visible at the upper left-hand side of a picture that Vanessa Bell painted at the house while staying there sometime in the early 1950s.

Bell, accompanied by Duncan Grant, was visiting at the invitation of the property’s unconventional owners: a coterie of cultured men who bought it shortly after the end of war in 1945 as a weekend retreat. Edward Sackville-West, Desmond Shawe-Taylor and Eardley Knollys were Oxford undergraduates together in the 1920s, and they were joined some years later at Long Crichel by Raymond Mortimer, the literary editor of The New Statesman. All of them were associated with the wider ‘Bloomsbury’ network of writers and artists.

The house was mainly used to keep their books and gramophone records. However, it was also a retreat to which they could invite some of the most flavourful figures in contemporary British culture – among them Somerset Maugham, E.M. Forster, Graham Greene, Anthony Asquith, Lord Berners, Nancy Mitford, Benjamin Britten, Lennox Berkeley, and Laurie Lee. While Eardley painted pictures of the surrounding country, Eddy and Desmond worked on their shared magnum opus at the house: The Record Guide, first published in 1951, which gave a selected overview of classical music available on gramophone record at the time. Their description of the Hungarian composer and piano virtuoso Béla Bartók is characteristically pithy.

A more resolute and single-minded musician than Bartók is scarcely imaginable. Caring nothing for fame, fashion, or personal influence, he seems to have lived almost exclusively in his art…

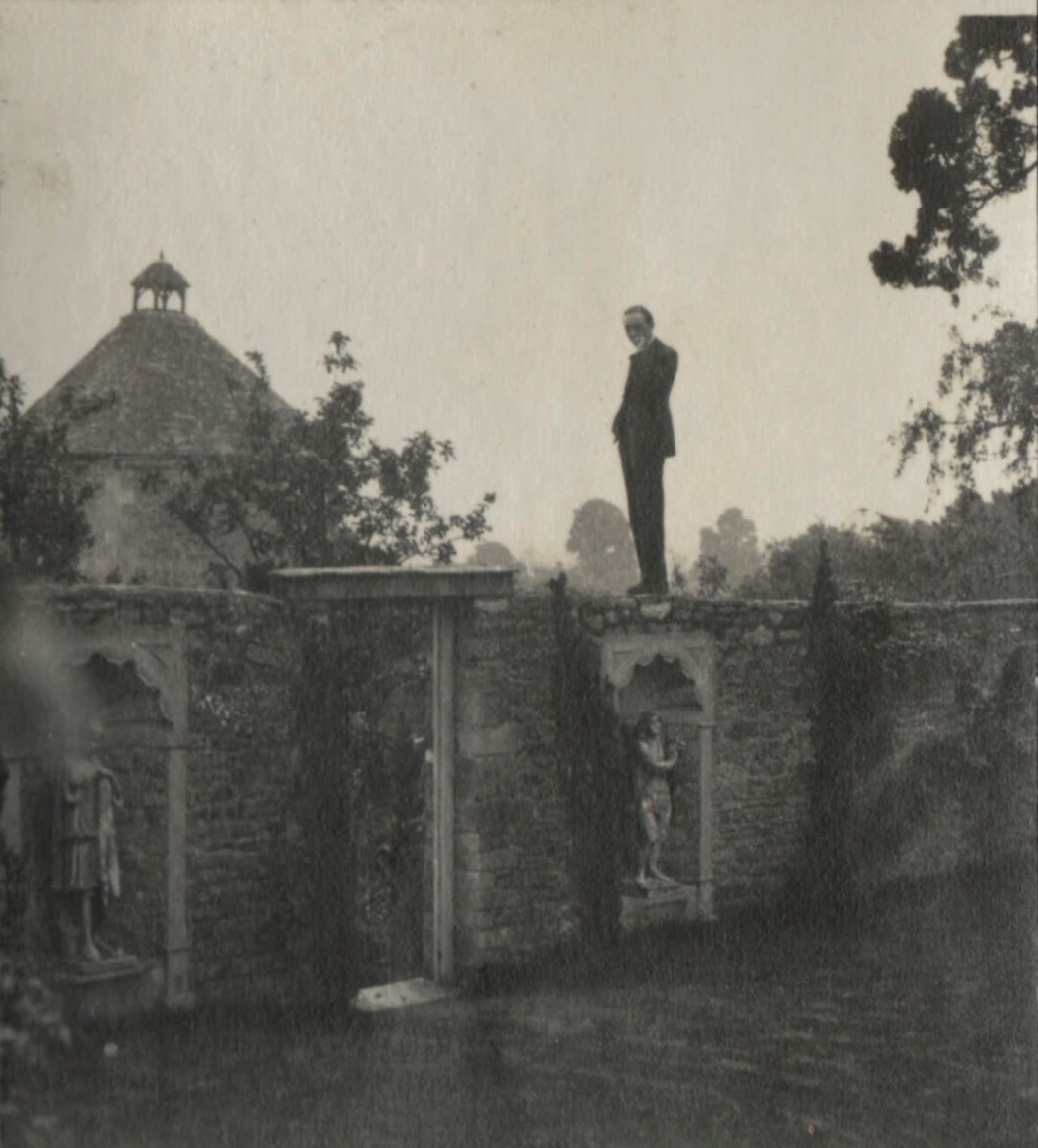

It was Eddy Sackville-West who wrote the Penguin Modern Painters monograph on Graham Sutherland, and who later asked him and his wife Kathy to stay at Long Crichel. Sutherland repaid the compliment with two portraits of Sackville-West. (The smaller of the two was immediately purchased by Birmingham Museums, such was Sutherland's status as one of Britain’s leading contemporary artists.) Writing in his diary on 18 January 1947, James Lees-Milne neatly summarised the cultured way of life at Long Crichel.

Eardley, Desmond and Eddy live a highly civilised existence here. Comfortable house, pretty things, good food. All the pictures are Eardley's, and a fine collection of modern art too. After dinner Desmond read John Betjeman's poems aloud, and we all agreed they would live.

Richard Shone remembers for InSight his visits to Long Crichel in the 1980s, which followed an initial visit to the house with Angelica Garnett in 1974.

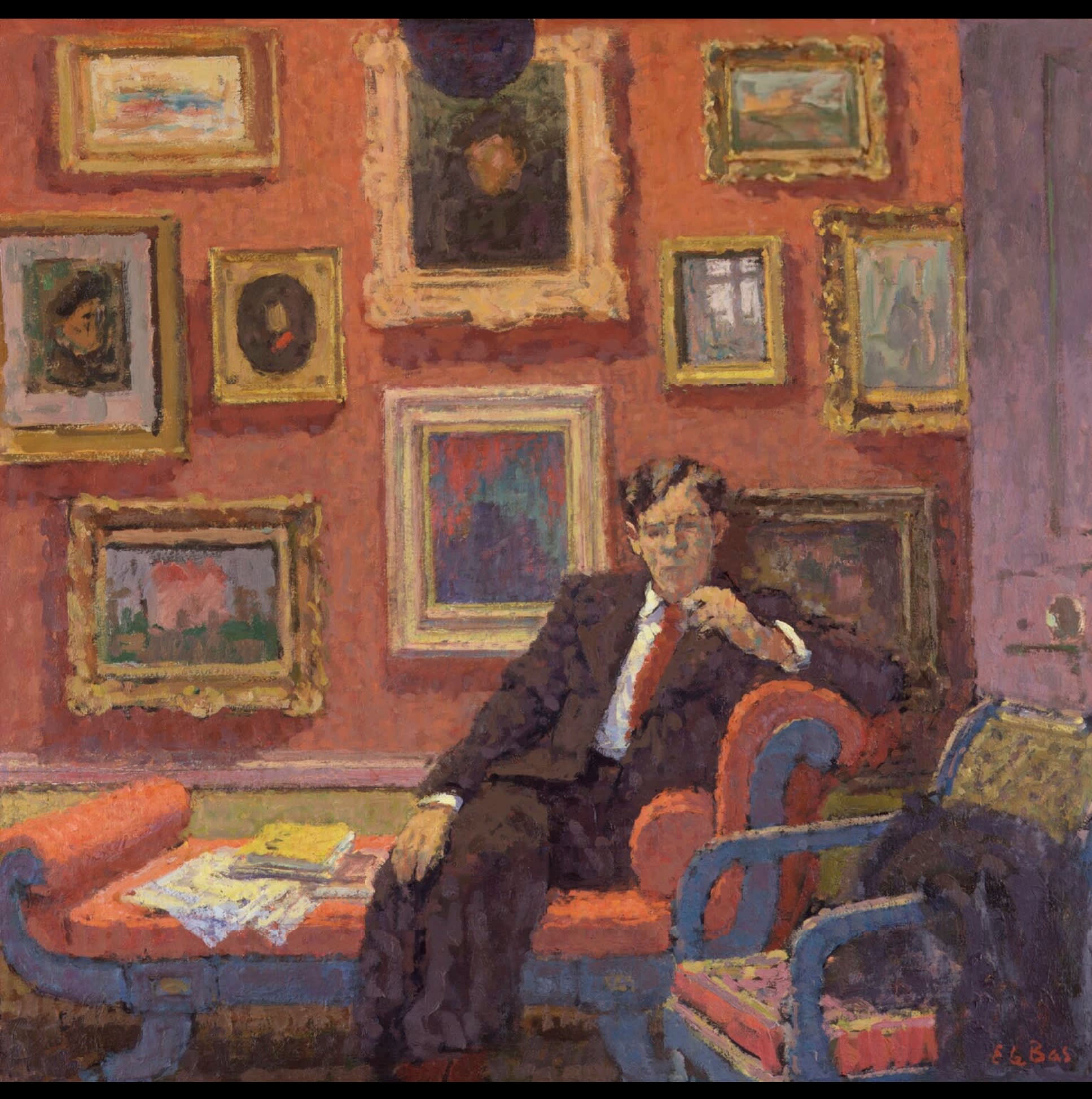

On my many visits to Long Crichel (often going by train with Frances Partridge), only Desmond of the original owners was left. Raymond Mortimer and Patrick Trevor-Roper were by then the other residential partners. Talk, music, books, etc. filled one’s days as well as walks with the house labrador. There was a resident cook/housekeeper; good meals; plenty to drink; and Desmond an attentive and adorable host. Eardley Knollys had taken away his own collection of pictures when he left, but he had also inherited Sackville-West’s collection in 1966. Some of this remained, including works by John Banting, Adrian Ryan and Graham Sutherland. (When Vanessa Bell first went to Long Crichel she roundly abused to her hosts the several Sutherlands hanging on the walls). But who the owners were of all the Grants and Bells (and the very amusing collage of Queen Victoria by Roger Fry), the several Sickerts (a beautiful drawing of Spencer Gore, for example), I never really discovered; probably Raymond. Most surprising perhaps was a vast canvas of classical ruins and dead game by Jan Weenix in Raymond’s bedroom. There were excellent pictures by William Scott and John Piper. And, memorable in the hall, a framed label for Henry James’s luggage, written in the master’s flowing hand. The dining room had curtains by Duncan Grant; there were plates by Bell; textiles by Piper; and some fine Boulle furniture. But it was the luggage label to Lamb House, Rye, that I really envied!

Bell’s painting shows a view from the drawing room at Long Crichel. The prominent mullions of the window lend a degree of formal clarity to the composition, while the arrangement of flowers is characteristically brushy and colourful. The combination of compositional clarity and painterly freedom was a winning formula which Bell had perfected earlier in her career. In Flowers in a Vase, Long Crichel House, it is put to good effect – evoking the restful, restorative mood of the house, and lingering over the “pretty things” which lived there like the elegant round-topped table, its surface reflecting the mauve sky outside. It is unlikely that the painting was made as a gift for Raymond Mortimer, and he probably bought it from Bell later. He was, nevertheless, the painting’s first owner, and the painting probably remained at Long Crichel when the time came for Bell to return to her own home along the coast in Sussex.

IMAGES:

1. Long Crichel House, Dorset

2. Vanessa Bell, Flowers in a Vase, Long Crichel House, c. 1951, Private Collection

3. A photograph of Eddy Sackville-West at Garsington Manor taken by Lady Ottoline Morrell, 1923-24

4. The Penguin Modern Painters monograph about Graham Sutherland (1943)

5. Flowers in a Vase, Long Crichel House (detail)

6. Edward Le Bas, Raymond Mortimer, c. 1946, National Portrait Gallery