To celebrate the beginning of summer, InSight is dedicating three articles to works by Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant. In another special edition, Richard Shone considers a drawing by Grant of the writer David Garnett (1892-1981) whose life was entwined with the Bloomsbury painters in surprising ways.

Duncan Grant

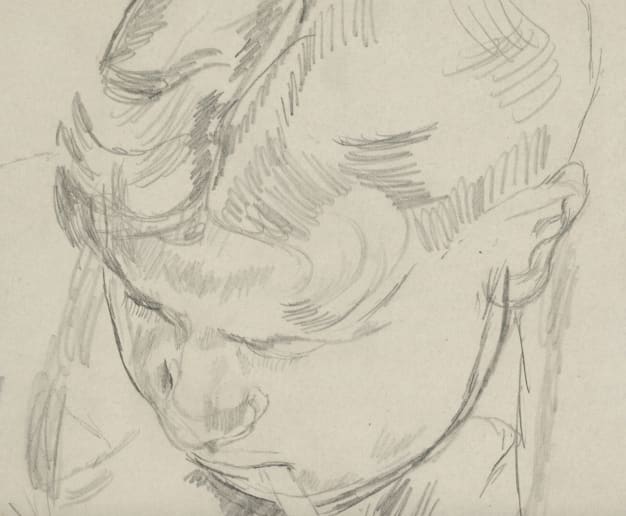

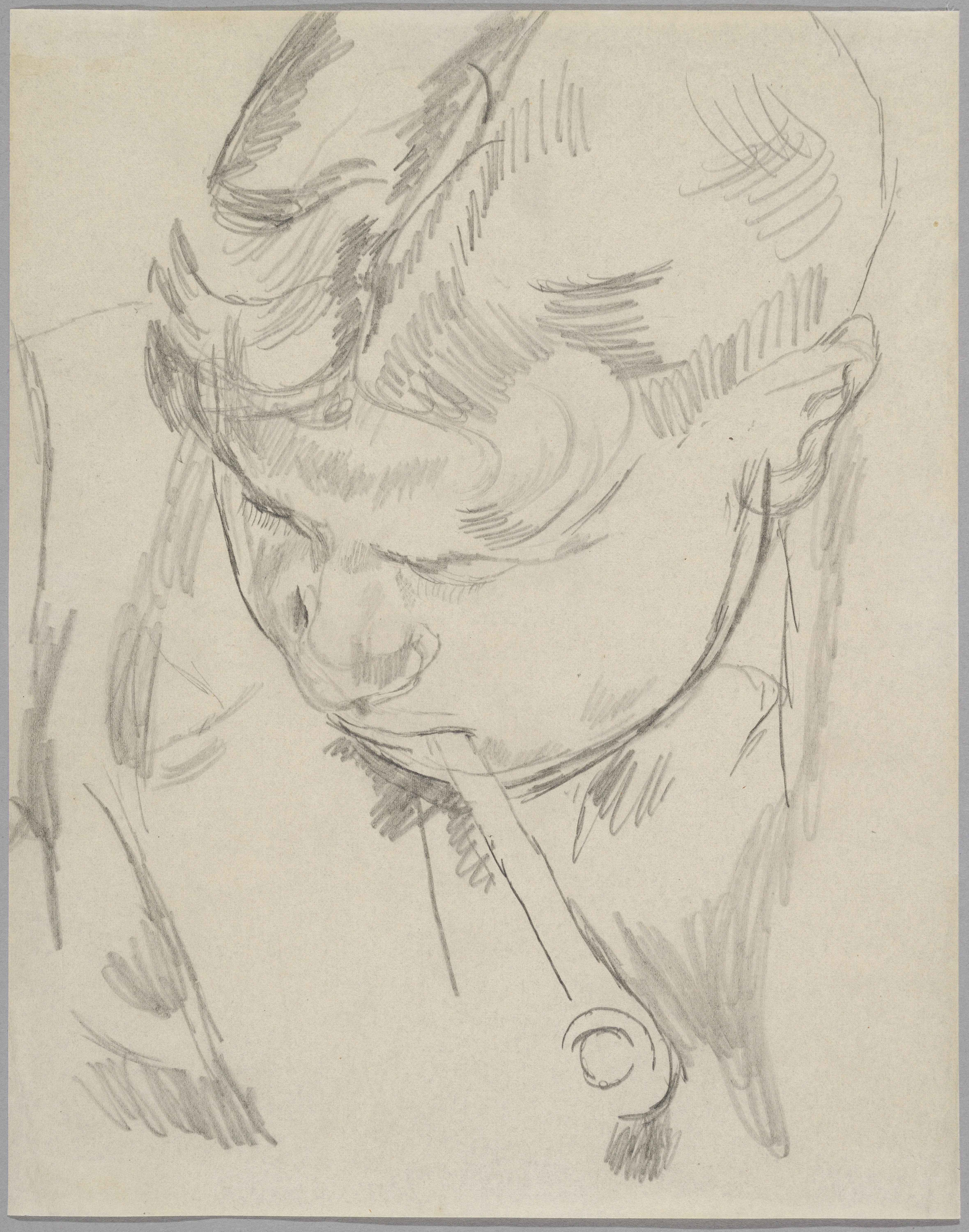

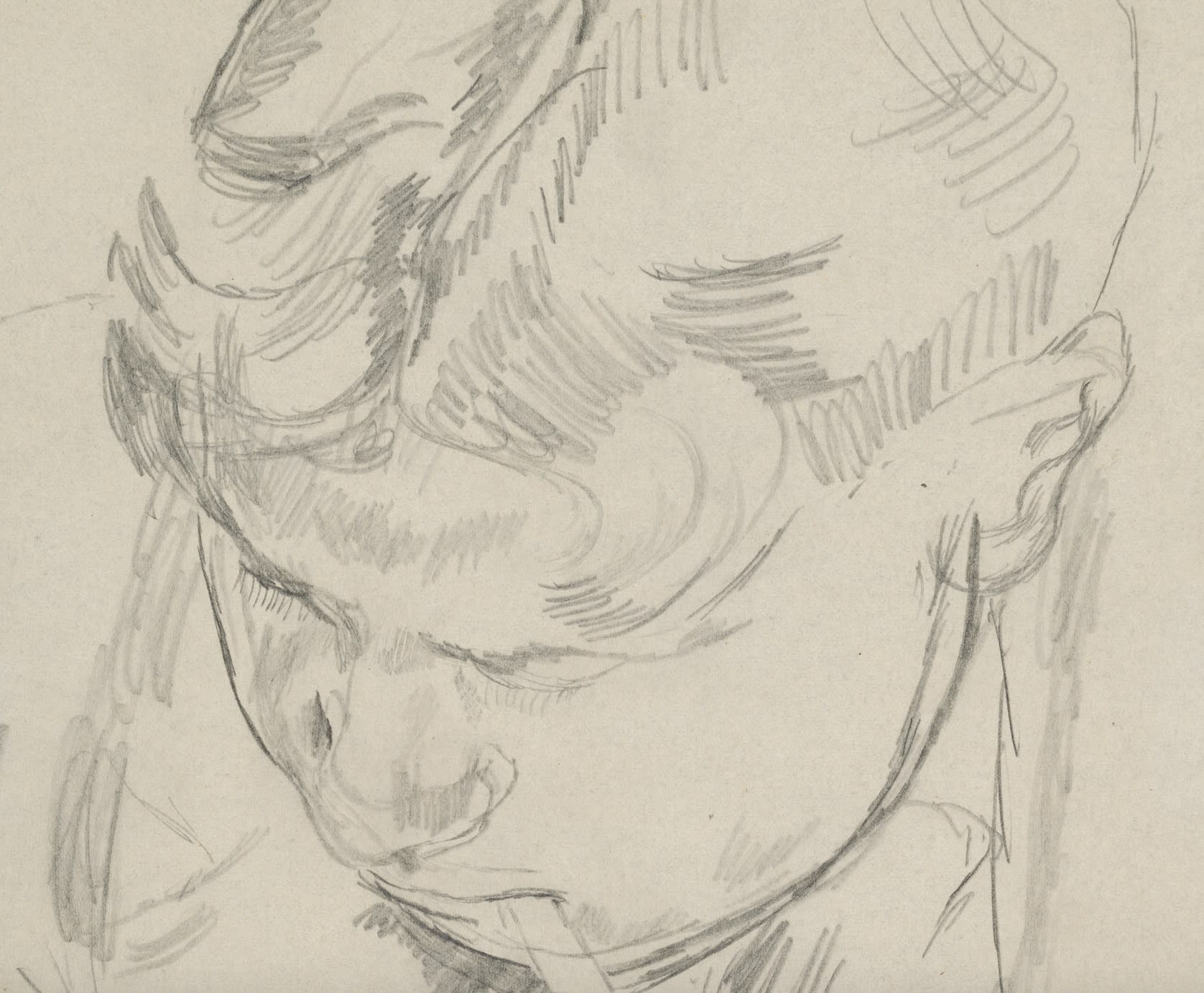

David 'Bunny' Garnett Smoking a Pipe, c. 1918

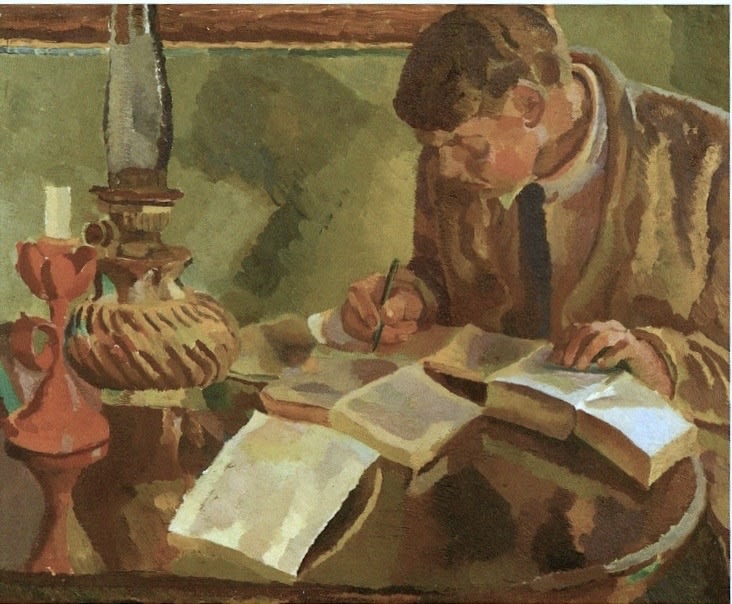

The pencil drawing, showing Garnett with a pipe, is almost certainly one of several studies made towards a painting by Grant of c. 1918-19 and called The Student. It shows Garnett working at a table with lamps and papers in front of him but no sign of the pipe. A very similar drawing, also for this painting, in which Garnett is pipe-less, was owned by his son Richard.

Garnett used to say that when he started to write seriously in c. 1919-20, Duncan Grant taught him, through example, how an artist might approach his or her work. Garnett sat to Grant on many occasions between 1915 and 1919. The most elaborate image is a big Interior of 1918, in which he is seen writing at a table while Vanessa Bell is painting, alongside him. There are also drawings and paintings of him from the 1920s and 1930s.

To his friends, Garnett was always known as Bunny – a nickname he acquired as a boy because he adored a little coat he wore that was made of rabbit skins. His father, Edward, was an outstanding publisher’s reader, notably encouraging D.H. Lawrence, Joseph Conrad and John Galsworthy. His mother, Constance, was the eminent and highly influential translator of recent Russian literature, especially of Tolstoy, Chekhov and Dostoyevsky. Bunny was born with several literary silver spoons in his mouth but as a youth he studied at the Royal College of Science, South Kensington, where he discovered a previously unrecorded fungus.

Garnett came to know most of the friends later known as Bloomsbury in 1914-15. Although predominantly heterosexual, he had a four-year affair with Duncan Grant and became an intimate friend of Vanessa Bell with whom Grant was living. Both men were conscientious objectors and worked on a fruit farm in Suffolk before going with Bell to live at Charleston in Sussex where the two men were farm labourers, securing their status as legitimate non-combatants. Bell’s two young sons, Julian and Quentin, were devoted to Garnett who taught them elementary science and country pursuits.

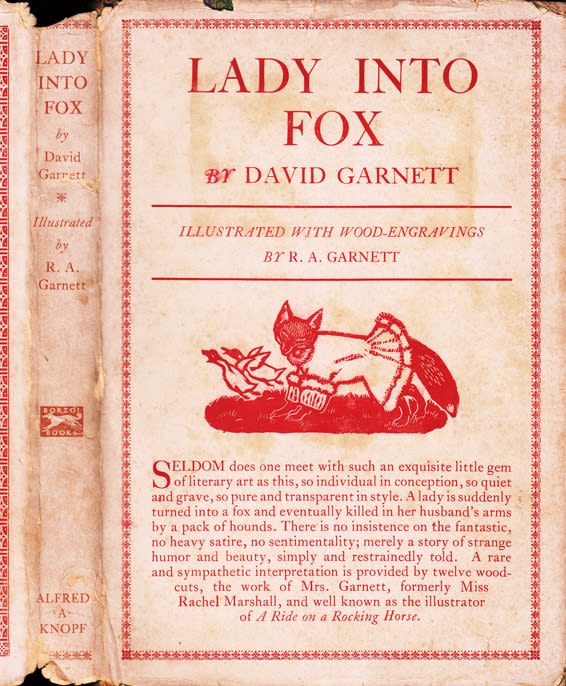

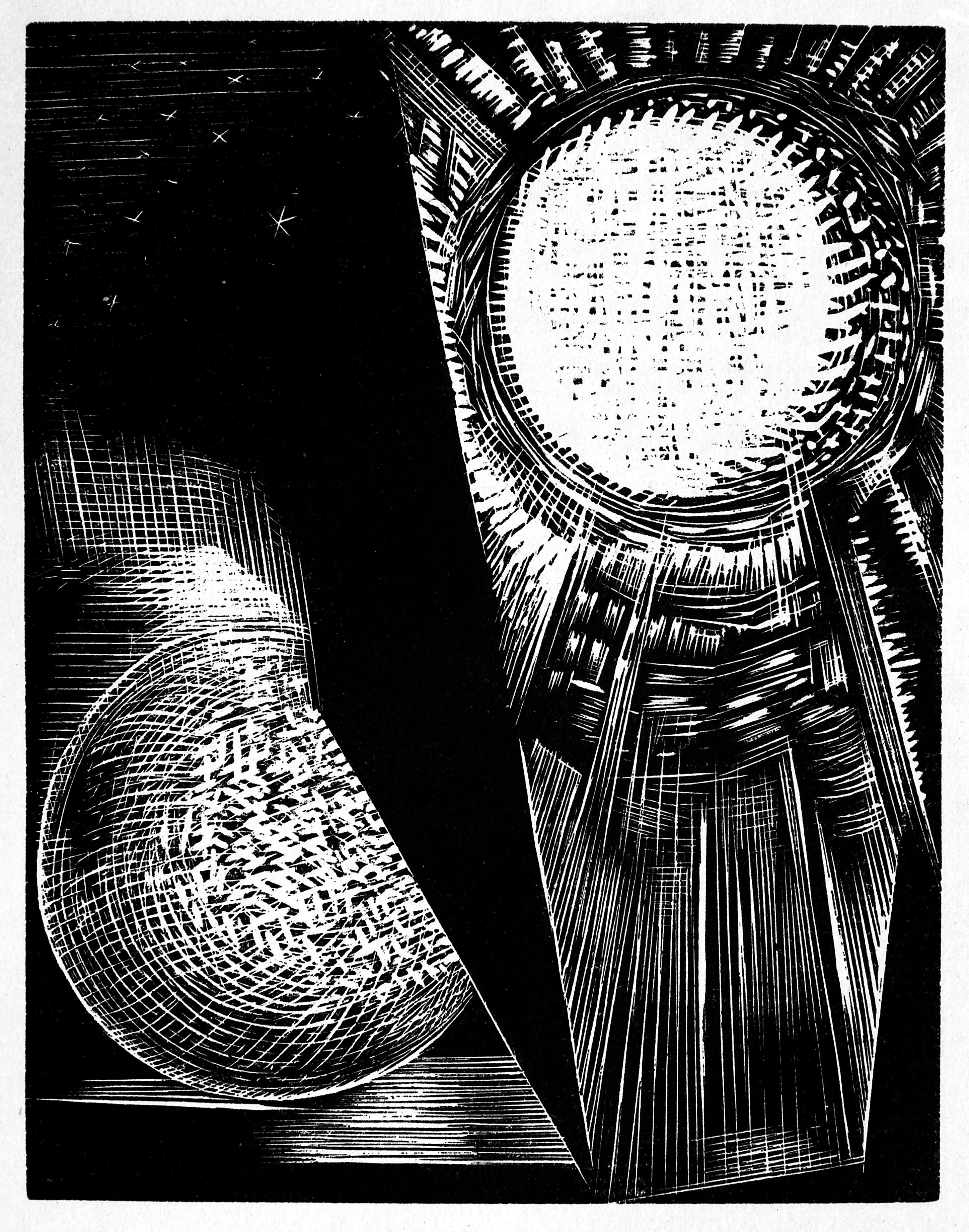

In 1919 Garnett’s close association with Grant and Bell waned. He moved to London and was soon married with two sons and the author of several curious, oddly personal novels such as Lady Into Fox, A Man in the Zoo and The Sailor’s Return. He became a well-known literary figure, publisher (co-founding the Nonesuch Press, which published Paul Nash’s Book of Genesis, 1924) and editor but was also a keen countryman, fisherman, beekeeper and dairy farmer at Hilton Hall near Huntingdon.

Grant painted two dashing Post-Impressionist portraits of Garnett in 1915. One is in profile (with the lower part of a looming female nude by Grant above his head) and another, a pair to Bell’s boyish image which, as Garnett’s daughter Henrietta commented many years later, ‘reeks of sex appeal’. There was another large painting of Garnett made in Grant’s studio in Fitzroy Street in which he is seated on a bright checked rug over a chair. It was not finished and when in c. 1970 Grant saw it again he decided, unfortunately, to complete it. I remember ‘sitting for Bunny’s hands’ in the Charleston studio; Grant went on with the head and completely spoilt the initial sketch.

Years later, Garnett was at the centre of one of Bloomsbury’s big scandals when, in 1942 he married Angelica, Duncan’s and Vanessa’s daughter. Garnett had been present at her birth. This caused considerable disquiet – she was twenty-six years younger than he. There were awful scenes and Grant and Garnett did not speak for some time; when appealed to, Maynard Keynes advised Duncan and Vanessa not to interfere. Reconciliation came about only gradually, especially through the birth of four daughters to whom Vanessa was particularly devoted. In Bell’s painting of the Bloomsberries gathered for a meeting of the Memoir Club, it is noticeable that she is seated next to Garnett but both have their backs to us.

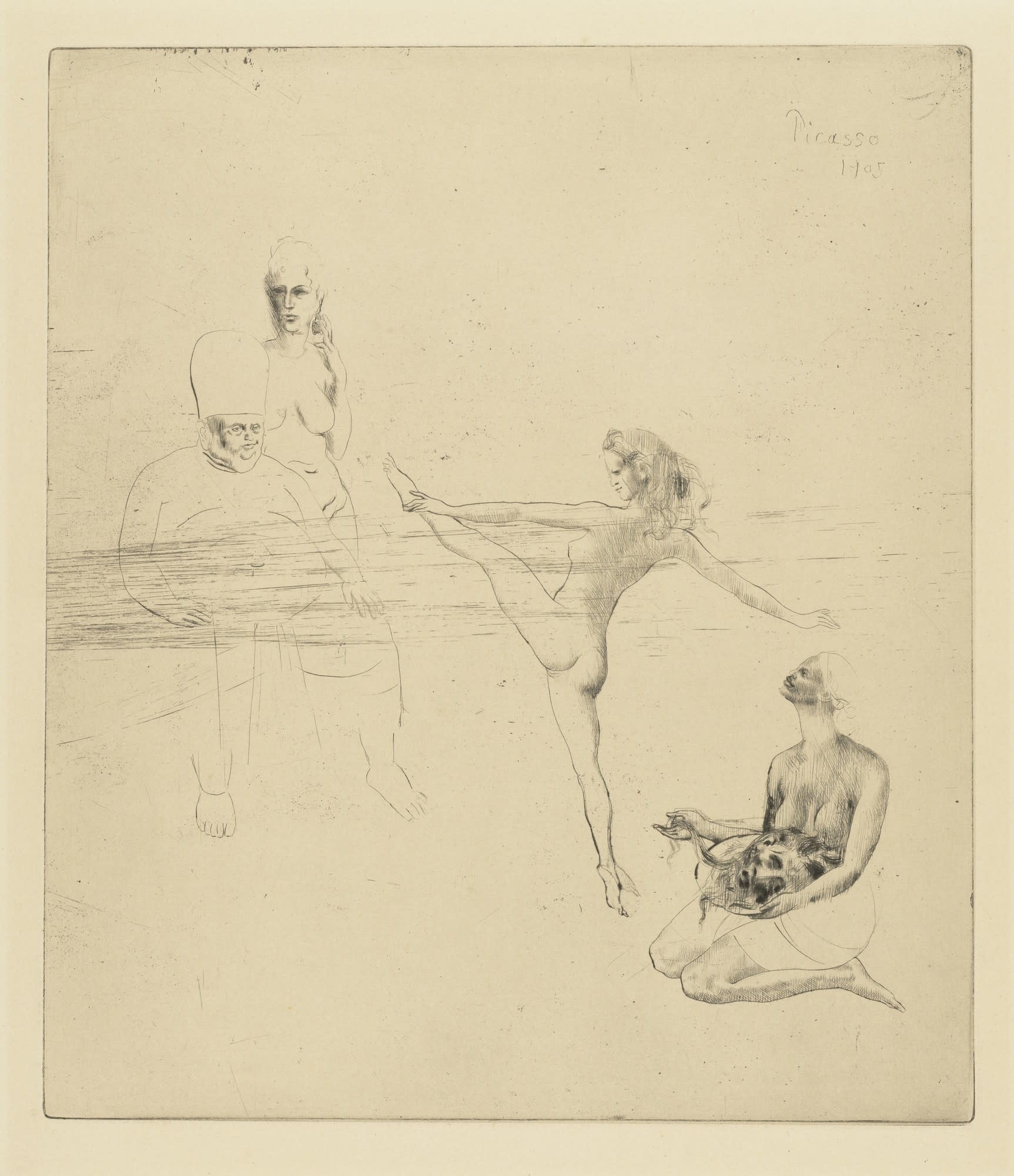

Both Garnett’s wives were artists, as was his daughter Nerissa. He was a thoroughly literary man who, unusually, loved pictures and would go to the London galleries and liked talking art. His house, Hilton Hall, was filled with pictures and he would proudly point to a Picasso etching, Salomé (1905) ,which he had bought ‘before everyone bought Picassos’. Those who knew him in later years remember his slightly strangled, very slow speaking voice (you could fit a sentence in between two of his words), his superbly white hair, French beret, excellent cooking, elaborate and amusing stories about people he loved; his passion for women and his devotion to cats.

IMAGES

1. Duncan Grant, David ‘Bunny’ Garnett Smoking a Pipe, c. 1918, graphite pencil on paper, 24 x 19 cm

2. Duncan Grant, The Student, c. 1918-19, Private Collection © The Estate of Duncan Grant

3. Duncan Grant, Interior, 1918, Ulster Museum © The Estate of Duncan Grant

4. Duncan Grant, David Garnett in Profile, 1915, Private Collection

5. The US first edition of David Garnett’s book Lady into Fox, published by Alfred A. Knopf in 1923

6. Paul Nash, The Creation of Sun and Moon from Genesis (1924, Nonesuch Press)

7. Vanessa Bell, The Memoir Club, c. 1943, National Portrait Gallery © The Estate of Vanessa Bell

8. Pablo Picasso, Salomé from the Saltimbanques series, 1905, Museum of Modern Art, New York © Succession Picasso

9. Duncan Grant, David ‘Bunny’ Garnett Smoking a Pipe, c. 1918 (detail)