This third InSight in our three-part focus on Leon Kossoff addresses a work from the 1970s: painted in the artist’s studio in Dalston, looking down on the tracks of the overground line between Hackney and Canonbury.

Leon Kossoff, Dalston Lane, 1974

Throughout Kossoff’s career, railway lines were a recurring subject: the wide sprawl of tracks behind his studio at Willesden Junction, the Underground line at the end of his garden, and the overground route near his studio in Dalston. After leaving his studio at Willesden Junction in 1965 he started working exclusively from a workspace in his home at nearby Willesden Green. Perhaps in search of something new, however, he rented a second studio at Dalston between December 1971 and 1975. The change of environment had the desired effect, and a series of work was prompted by the view from his expansive window: a long sweep across the sprawling, downbeat rim of London.

A catalogue raisonné of Kossoff's oil paintings is currently being prepared by Andrea Rose, who recently described for InSight the urban geography which lies behind Dalston Lane, Summer.

At Dalston Junction, he had views looking west towards Canonbury and east towards Hackney. The landscapes painted during this period look out over the tracks of the North London Line in both directions, cutting through densely packed streets, with small traders’ shops and lock-ups on the west side. Looking east, as this painting does, the tracks emerge from under a road bridge, with a brick embankment and a verge of green grass running alongside, until the metals disappear into a tunnel. Dalston had long been home to immigrants. A sizeable Jewish population was living there in the pre-war period, followed in the post-war years by successive waves of immigrants from the Caribbean, Turkey and Vietnam. The largest immigrant group to settle in the area, however, was from Germany in the mid-19th century. They built, among other things, the German Hospital, a redbrick, gable-ended sanatorium, which appears against the skyline of Kossoff’s views of Hackney. To the right of the Hospital, a church spire rears into the air and, tipped up towards us, is Dalston Lane, with people walking past hoardings, or working in the local timber yard. This is Kossoff’s Venice, his city of vistas and movement, translated to the everyday shopping streets of the north.

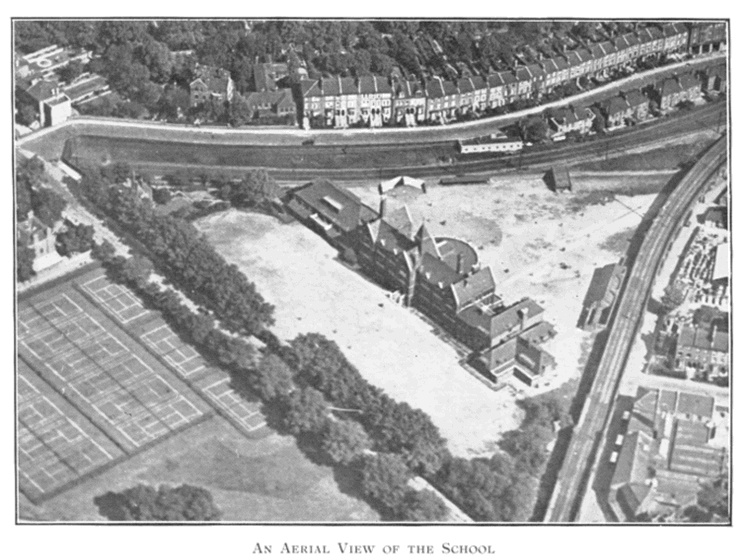

Dalston was not far from where Kossoff went to school before the Second World War broke out. Today Hackney Downs is a successful academy, redubbed ‘Mossbourne Community Academy’, following a Blair-era reconstruction in response to failings which ultimately forced the old school’s closure in 1995. During Kossoff’s time, however, it was a successful grammar school under the patronage of the Grocers’ Company. Given the artist’s later attraction to railway tracks, it is hard to ignore the salient urban situation of the school: it was located at the intersection of two diverging train lines. The air must have thrummed with the sound of passing trains.

Kossoff’s connection with London was not incidental, a simple affection for the places he had lived. In a short text for his solo exhibition at Fischer Fine Art in 1974, he wrote about the extra-sensory connection he felt with the city.

I was born in a now demolished building in City Road not far from St Paul’s. Ever since the age of twelve I have drawn and painted London. […] The strange ever changing light, the endless streets and the shuddering feel of the sprawling city lingers in my mind like a faintly glimmering memory of a long forgotten, perhaps never experienced childhood, which, if rediscovery and illuminated, would ameliorate the pain of the present.

The surface of Dalston Lane, Summer has a masticated plasticity. The old Lutheran Church on Ritson Road and the German Hospital, pictured above, seem to ripple under the turbulent grey sky. The paint is thick and gum-like, and the artist’s energetic brushwork results in an open-grained finish. This is characteristic of Kossoff’s work from the period. He used paint manufactured by Stokes of Sheffield, a glutinous and full-bodied industrial product known for its high content of linseed oil. The thickness of this paint allowed Kossoff to apply it, manipulate it and scrape it away, and it is by this rhythmic activity that his works were constructed. As he explained, his working procedure progressed along a knife-edge between instinct and calculation.

Everyday I work over the whole board, I usually scrape off the previous day's work. Occasionally, when I am not sure, I let a board dry out and work on it later. I never work on bits. Either a whole structure emerges or I start again. I don't know why the paint goes on the way it does, but I do know that, if I think about it, I might as well scrape off and begin again.

The high watermark of Kossoff’s Dalston period was in 1974. Though he always worked on several paintings simultaneously, it was in the summer of that year when a number of them came to fruition, including Dalston Lane, Summer and a comparable work in the Tate Collection, Demolition of the Old House, Dalston Junction, Summer 1974. These paintings are large and powerfully worked, with pulsating surfaces and a vitality that grew from three years spent looking out of the same window, pondering the distance, and digesting it.

IMAGES

1. Leon Kossoff, Dalston Lane, Summer, 1974, oil on board, 106.7 x 123.2 cm

2. A view from the window in Kossoff's Dalston studio

3. Dalston Lane, Summer (detail)

4. An aerial view of Hackney Downs' School, situated beside two converging overground railway line

5. Dalston Lane, Summer (detail)

6. Leon Kossoff, Demolition of the Old House, Dalston Junction, Summer 1974, 1974, Tate Collection

All works by Leon Kossoff © Leon Kossoff Artistic Estate