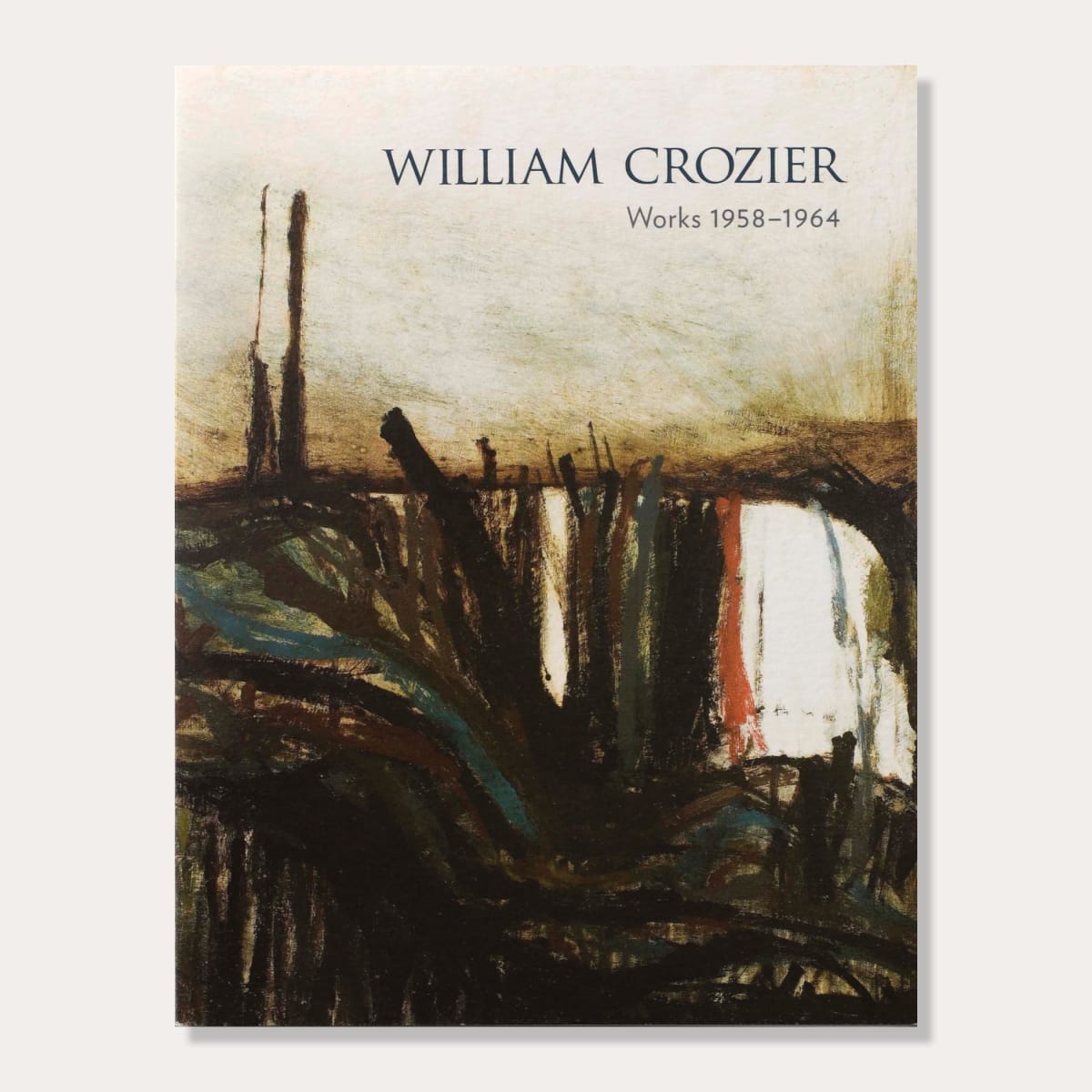

William Crozier: Works 1958 - 1964

William Crozier (1930-2011) liked to quote Somerset Maugham's observation in Of Human Bondage that 'we are not all of a piece', though without any sense of irony that he himself disproved the rule. The visitor to this selection of paintings of 1958 to 1964, many of which have not been seen for over 50 years, was struck by the consistency in Crozier's art, seeing a continuum between the emotional tenor of this early work and the better known, luxuriantly colourful landscapes and still lifes painted after 1984. Yet Crozier's work is almost invariably inspired by a sense of alienation, sometimes by the exquisite ache of exile. In these early works his concern with the human condition is raw and explicit; it is the very object of the image.

How must these obsessive images of landscape and the human figure be understood and located in the history of post-war art? Paris and Existentialism marked William Crozier for life. He had immersed himself in Sartre and Surrealism while at Glasgow School of Art (1949-53) and he visited Paris as a student and young graduate, drinking in the atmosphere of St Germain and finding in Existentialist philosophy, art and politics the paradigms for his emergent art as much as a personal moral compass. Moving from Scotland to England, Crozier held a maverick position in the London art world of the 1950s, an artist at the forefront of avant-garde British art while existing simultaneously at one remove from it.

The Essex landscapes in this exhibition were among the paintings which first brought him to the attention of the London art world. This was in 1958 when his landscapes were shown, first at the Drian Gallery, and from 1959 at Arthur Tooth and Sons Gallery where he was contracted from 1960 to 64. Both galleries brought him great critical success at the time, provided the opportunities to exhibit in France and Italy and the financial means to live in Spain for a period in 1963. His work was admired by Herbert Read and came to the attention of a wider European audience through the writings of Michel Ragon.

Space and time are the dynamic elements of these early paintings. The speed of the brush, the stabbing drawing in paint, the shallow, claustrophobic space and, most of all, the sense of time compressed into the action of making the painting, all convince us that these are landscapes of the mind, not place.

The figures that emerged in the landscapes around 1960 remind the 21st century viewer that here was an mind indelibly printed with the horrors of war - Crozier was a lifelong pacifist and atheist, commitments reaffirmed by a visit to Bergen-Belsen in 1969. Between 1960 and 1975 Crozier frequently returned to the figure, giving his works the dispassionate titles of 'portrait', 'selfportrait , or 'figure in landscape'; rarely if ever the melodramatic descriptor of 'skeleton'. His subject lay in humanitas, not the macabre, and he saw no distinction between his figure paintings and landscapes. All were images created to 'convey a sense of austerity and isolation, of emotional unease and perhaps a suggestion of tragedy' but as time went on they also displayed theartist's increasing love affair with colour and the medium of paint.

Crozier continued to mine the subject of skeletal figures in the landscape until 1975, when they stop abruptly. He returned to the landscape, now inspired by the specific locations of Hampshire and West Cork, always emphasizing that for him, landscape was only ever the vehicle, not the subject of his art.