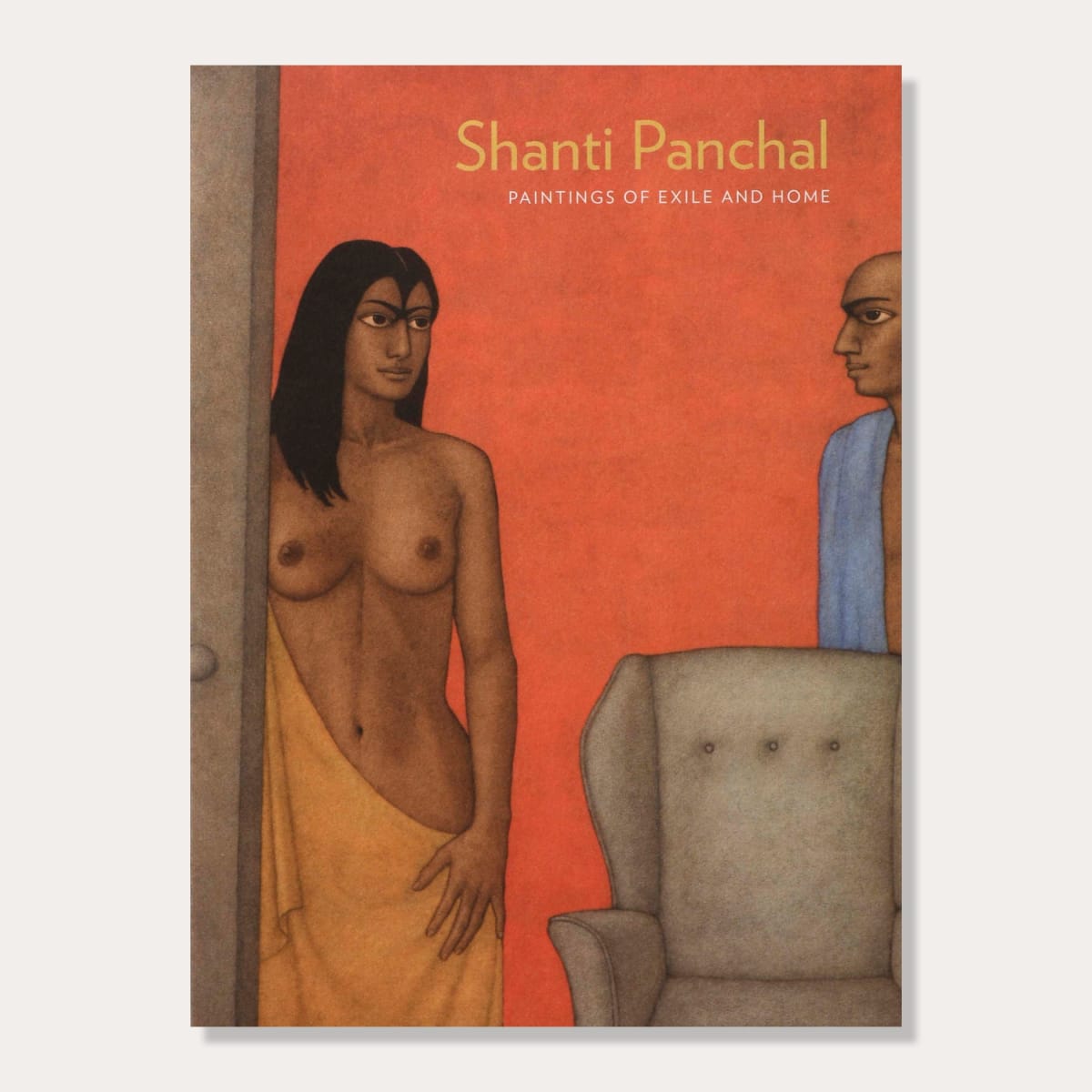

Shanti Panchal: Paintings of Exile and Home

The London-based painter Shanti Panchal who was born in the mid-to-late 1950s (his exact birth date is unknown) in the Indian village of Mesar in northern Gujarat, attended the Sir JJ School of Art in Bombay, and first came to London (on a British Council Scholarship) in 1978. His often large-scale, fresco-like watercolours of subtle vibrancy are at once movingly archaic and challengingly contemporary in their compassionate humanity.

His spaciously abstracted works are partly inspired by Indian miniaturist painting and Buddhist and Jain frescoes but also by the visionary figuration of El Greco, Mark Rothko's immense fields of colour and the haunting backdrops of Francis Bacon. He relates the attenuated abstract element in his work to the remote village landscape - 'very dry, ochres and reds and browns, all sand and mud-wall houses with red tiles', 'monumental skies' and' deep, dark nights and burning days' - of his childhood.

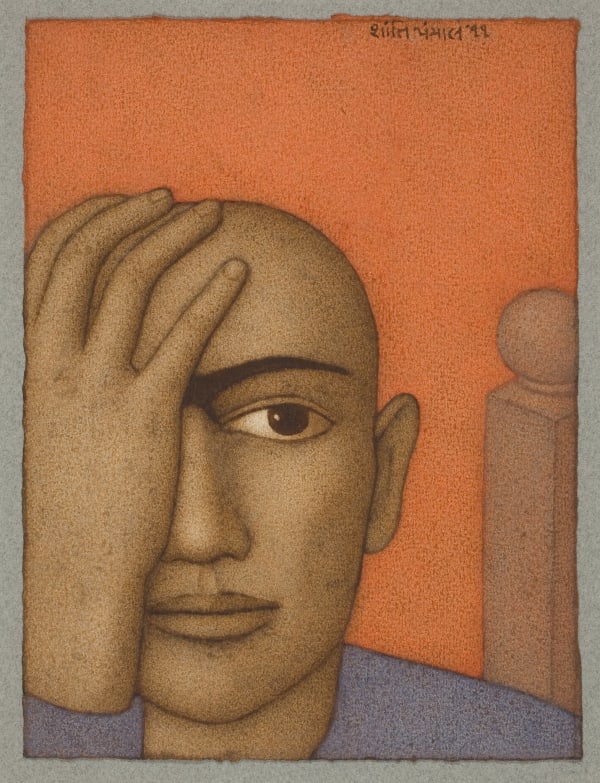

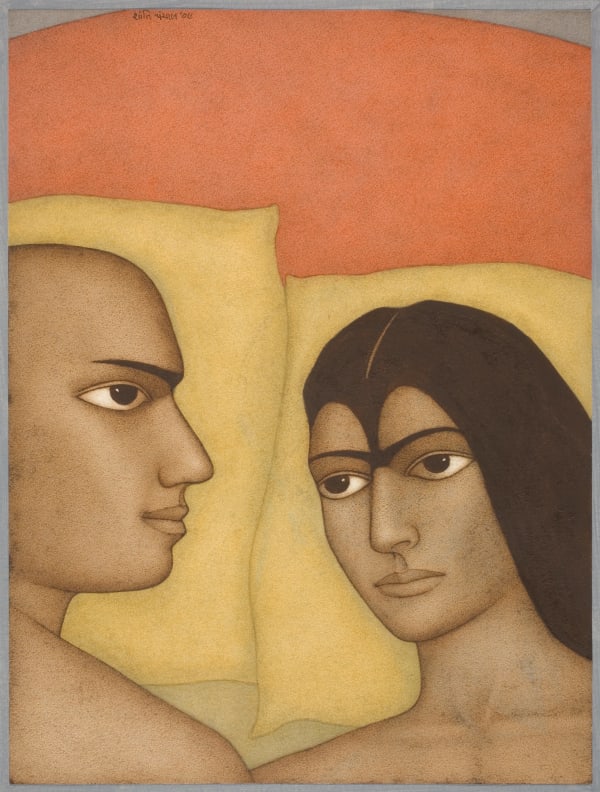

In the early 1980s Panchal developed a dynamically innovative yet deeply meditative way of painting, whereby 'watercolour is not just painted on the surface but infused into the hand-made paper many times, and I scrape that with hard oil-paint brushes and use blotting paper. The kind of depth you achieve is amazing.' His subjects here are remarkably diverse. They include pillow-talking lovers whose nobly sculpted countenances speak paradoxically of exquisitely silent communication; the artist's three sons blissfully bonded through the resonance of music, as one of them plays the guitar and sings in an austerely toned, minimalist setting at whose far end is a slender rectangle of warm ultramarine blue - a transcendent glimpse perhaps of sky beyond; a young woman focussing on the infinitesimal vacancy where Moore's Three Points concur in Henry Moore's 1939-40 sculpture of that title (Panchal had been moved by a Moore sculpture show he had seen at Kew Gardens, and relates Moore's form here to the Hindu-Buddhist symbol of the trishula or Shiva's trident).

A hieratic painting describing a small group of peaceably poised Jain monks in their pristine white garb and obligatory rectangular white cloth mouth coverings in a monumentally simplified setting, stands side by side with a picture of a pair of young 'hoodies' in a bleak, surreally sealed-off square (portrayed following the 2011 London riots). Panchal intentionally depicted the latter figures as alienated yet dignified adolescents not subsumed by urban restlessness and mayhem.

In the ambiguously titled The Last Order, the upright yet easeful young man and lovely woman seated at a round table, are seen in an enigmatic passage of their relationship - the start of their romance (at the end of the meal) perhaps, or the end of the affair even; maybe being snared in a fresh emotional entanglement or embarking on a new voyage of discovery... The immaculate brilliancy of the man's chef whites has been conjured up by the artist scraping away (with a hardened oil paint brush) layers of burnt sienna, grey and blue to reveal the paper's original luminosity.

Similar poignant paradox lies at the heart of Admiration: two near-naked lovers, yearning for intimacy, are each seen as distinctly solitary yet united in their searching vulnerability. Their emphatically large, lustrous eyes, resembling those in a Jain miniature, at once focus within and look infinitely beyond the picture frame. It is a characteristic and original feature of a Panchal portrayal that the woman's hair extends downwards over part of her forehead, so that it meets up with her striking eyebrows, formally rather like Moore's Three Points or Shiva's trident. For the artist this physiognomic form, which he came up with one day by happy accident when moving from oil paint to watercolour as his preferred medium, symbolises a third eye of intuitive energy and spiritual discernment.

The admiring figures are placed at the edge of things: the youthful yet seemingly quite ageless man bisected by the right-hand edge of the picture (the blue towel cascading over his shoulder like a refreshing stream); the slim, graceful woman standing on the room's threshold, wearing an ordinary lemon-golden towel as if it were some regal wrap or the unsensationally lowered sari of a dancer resting in a still, timeless moment. The empty, silvery grey armchair here (according to the artist, curiously resembling in form Ganesh, the Hindu elephant-headed deity) may suggest an element of the capacious mutual understanding (as well as yet-unrealised potential of the relationship) between the lovers. Panchal says that 'the foreshortening of the figures within the wider composition, the sense that there is a further narrative beyond the edges of the picture, gives us a mysterious glimpse of a bigger picture in the scheme of things'.

PHILIP VANN

Philip Vann is author of numerous books on 20th century and contemporary British and Irish artists, and the critically acclaimed Face to Face: British Self-Portraits in the Twentieth Century.

-

Shanti Panchal, The Arch, 2008

Shanti Panchal, The Arch, 2008 -

Shanti Panchal, Millie, 2010

Shanti Panchal, Millie, 2010 -

Shanti Panchal, The Robe, 2010

Shanti Panchal, The Robe, 2010 -

Shanti Panchal, At School, 2012

Shanti Panchal, At School, 2012 -

Shanti Panchal, The Interior, 2007

Shanti Panchal, The Interior, 2007 -

Shanti Panchal, Moore's Three Points, 2007

Shanti Panchal, Moore's Three Points, 2007 -

Shanti Panchal, The Last Orders, 2012

Shanti Panchal, The Last Orders, 2012 -

Shanti Panchal, Seaking, 2011

Shanti Panchal, Seaking, 2011 -

Shanti Panchal, Profile, 2012

Shanti Panchal, Profile, 2012 -

Shanti Panchal, Pelvis, 2009

Shanti Panchal, Pelvis, 2009 -

Shanti Panchal, Pillow Talk, 2009

Shanti Panchal, Pillow Talk, 2009 -

Shanti Panchal, Hoodies in the Square, 2011

Shanti Panchal, Hoodies in the Square, 2011 -

Shanti Panchal, Cadence of the Heart, 2011

Shanti Panchal, Cadence of the Heart, 2011 -

Shanti Panchal, The River Bank, Maldon, 2011

Shanti Panchal, The River Bank, Maldon, 2011 -

Shanti Panchal, Admiration, 2007

Shanti Panchal, Admiration, 2007